In his valuable overview Magic in the Ancient Greek World, Derek Collins opens with the important question regarding the understanding of magic and its differentiation from religion.

Attempting to define magic is a risky, if not impossible undertaking. As foremost scholar of Western Esotericism, Wouter J. Hanegraaff, remarks:

Magic is a wretched subject… it seems to resist all attempts at defining its exact nature, thus causing serious doubts about whether it refers to anything real at all - or if so, in what sense… Nobody has seemed capable of exorcising it from the academic vocabulary… Like the monster in cheap horror movies, “magic” always keeps coming back no matter how often one tries to kill it.

Wouter J. Hanegraaff, “Magic,” Cambridge Handbook of Western Esotericism, 393.

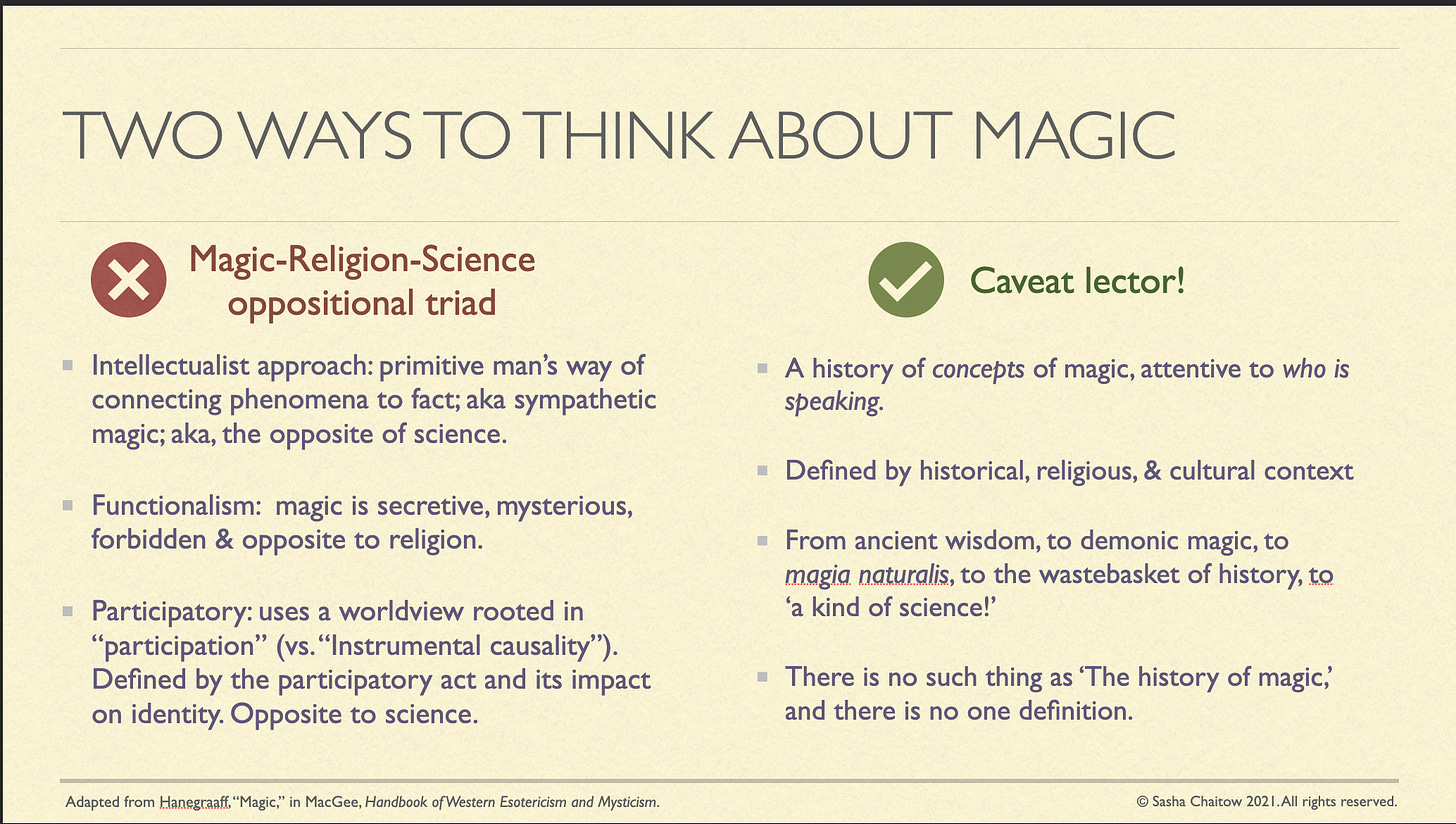

He goes on to outline the various attempts made to think about and discuss magic in academic scholarship, and the pitfalls involved, summarised in the slide below:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thyrathen: Greek Magic, Myth, and Folklore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.