Firstly, a very Happy New Year to all my readers! The twelve days of Christmas are not quite up, but I’m back in my office with deadlines to meet, after duly holding local New Year’s traditions! Here’s the Skilla wild onion I unearthed on New Year’s Day to bring luck to the home for the year ahead. Read more about this in a caption in this post!

And here’s the smashed pomegranate. My dog Machi stepped over it instead of me, so technically she’s our first-footer for this year. But she and her sister Kirki won the New Year’s lucky penny this year, so maybe that was her bringing luck back in the house! If you missed my series on Greek Midwinter traditions, here’s the one with all the New Year’s traditions and links to the rest!

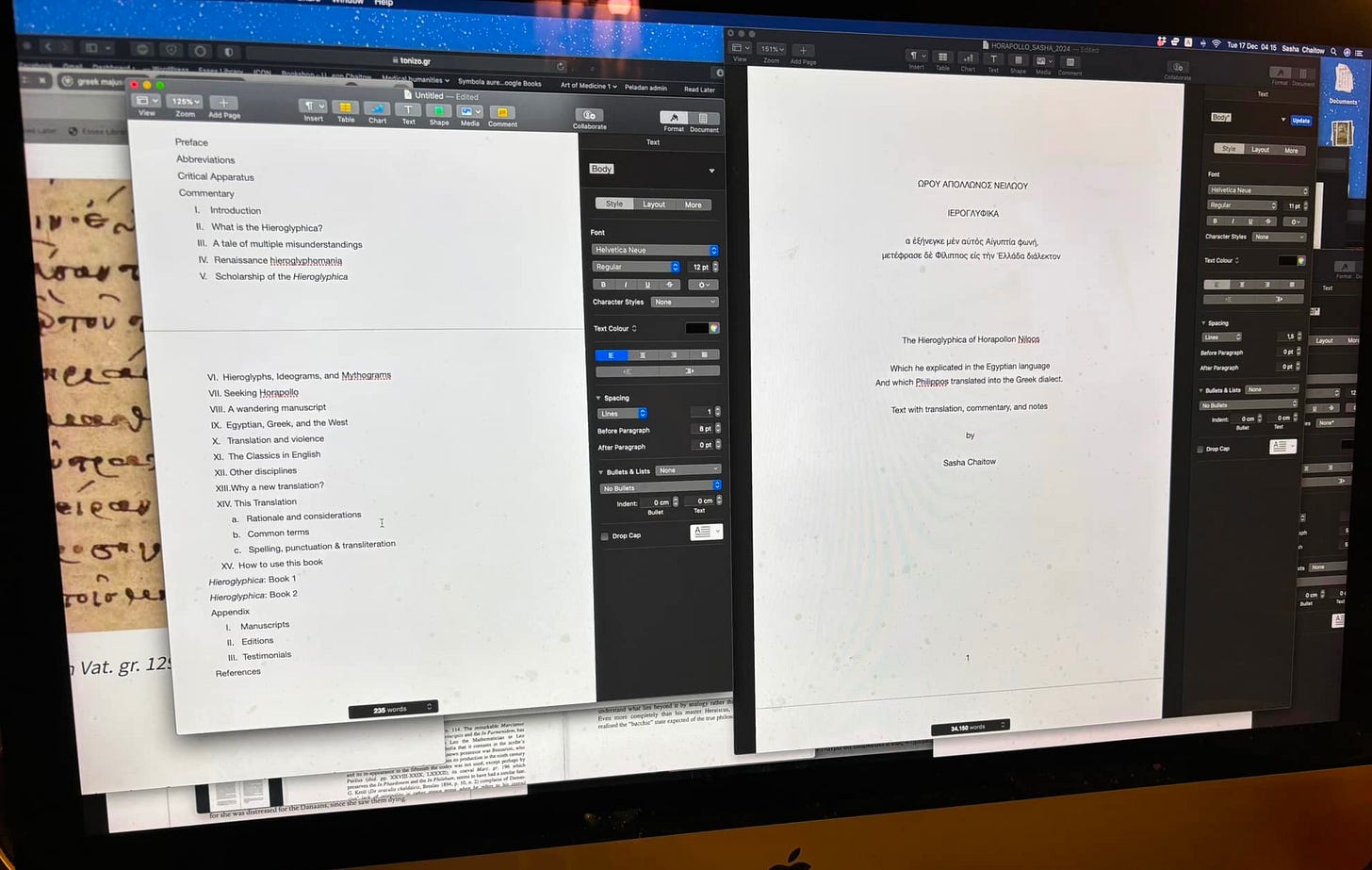

Traditions aside, it’s been back to earth with a bump as I race to finish a long overdue manuscript.

I’m working on a late antique era manuscript text known as the Hieroglyphica of Horapollon, one of very few sources on the transmission and knowledge of Egyptian hieroglyphics in late antiquity. I can’t share too much on this here as it’s due for publication, but one aspect I do want to share has to do with the wider intellectual context of the time when this text was produced.

Late antiquity (ie, 4th-6th centuries CE), or, the early Christian Era, has often been thought of as the period when the final nails were hammered into the coffin of a moribund Paganism by rabid Christian mobs. But this is an altogether far too simplistic, partisan, and frankly incorrect summation of the era. Paganism did not altogether die, Christianity was not a solid, heterogeneous front, and there was far more diversity of thought and philosophy at that time than is generally discussed in non-specialist literature and fora. I’m paying especial attention to this in my introduction to the translation, because this context is important for understanding what the text actually represents.

What follows is a small preview from the commentary I have been writing over past weeks. News on publication and pre-orders will follow in due course. I have an amazing haul of fresh material to share with you, and I’ll be shaking up the themes and days I post on pretty soon (more on that in due course). For now, here is a snippet from my upcoming book, exploring how allegorical thinking saved Pagan myth. Needless to say, the book is fully footnoted and comes with hefty references, what follows is just a sample of what is to come.

Allegorising Paganism

The efforts to systematise pagan and philosophical thought that began in the early Christian era and climaxed in fifth and sixth centuries CE are the result of the polysemous entanglements with Christianity: both confrontational and stimulating, existentially threatening and ontologically regenerative.

The Neoplatonist attempts at preservation of tradition via synthesis, rejuvenation, concealment, or outright defiance ensured that by the fifth century, “contrary to a deep-seated tendency to view paganism as moribund, considerable vitality [remained] in the religious traditions of Hellenism, both in its rural and its philosophical form.”

This was neither consistent nor internally coherent, since Neoplatonists disagreed amongst themselves. Nevertheless, despite the heterogeneity of this context, “all this systematising of late pagan philosophical and religious thought ‘produced a doctrine and an identity.’”

A further method initiated with considerable success and unexpected results was that of allegorical interpretation and a dose of backfiring euhemerism (on which more in the book).

Myth is a vehicle of collective memory, shaped in a cultural matrix that imbues its narratives with meaning. The personification of the forces of nature and human attributes in god-forms, myths of origin, genealogy, aetiology, and divine justice form an additional layer of reality through which to make sense of the world. It is set apart from poetry, drama, and philosophy by way of its nature as tradition, rather than purposely crafted or aestheticised discourse.

Cyclical temporality mapped upon linear human lifetimes ensures both a sense of eternity, and a liminality particular to the experience of the sacred. Interpretations of myth, whether as part of a sacred rite, bedrock of cultural identity, or legends with details lost to time, depend on the meaning-making needs of both composer and interpreter and the context within which they are operating.

With regard to the interpretation of myth, is important to clarify the difference between allegorical composition or expression, and allegorical interpretation.

The terms allegory (composition) and allegorēsis (interpretation) are sometimes used to distinguish between them. In the case of allegory, a narrative tradition, text, or image is constructed with the intention of concealing allegorical meaning (“hiding a message under the cover of a figure”), and familiarity with the cultural context and conceptual frames of reference is necessary to decipher the figure and retrieve the intended meaning.

In the latter case, allegorical reading is a mode of interpretation applied regardless of the intention or qualities of the narrative, and may result in entirely new interpretations that depend on “slippage of one series of signifiers over a set of new or unanticipated signifieds," thus becoming “a device for the displacement from one type of discourse to another."

Allegorical reading - allegorēsis - of a text, symbol, image, or event consists of attributing deeper meanings to mythic figures, tableaux, or narratives, following rational, naturalistic, ethical, or metaphysical principles by way of correspondences, resemblances, and associations. Because there are no limitations to the sets of principles that can be applied in search of new readings, as a hermeneutic method it allows the uprooting of myths from their cultural substrate, allowing for their “progressive and increasingly broad reintegration into the frameworks of history and philosophy.”

Numerous allegories are attested in Egyptian myth, image, and text from the Middle Kingdom onward (with some earlier examples also extant). Three key modes are attested: personification; commentary on isolated phrases within a text; and fictional poetry or prose. Some of the earliest textual samples are attested in Egyptian literature as early as the Fourth Dynasty (2613-2494 BCE), but do not begin to appear in Hellenic material until two thousand years later in the Greek archaic period, by which time trade, political, and cultural exchange between Egypt and Greece had broadened and intensified.

…

Allegoresis in Greek thought

In Greek thought, early challenges to Homeric and Hesiodic descriptions of the gods by pre-Socratic philosophers led to efforts at allegorical interpretation that, some scholars claim, succeeded in preserving the archaic epics that had come under fire. Though intentional allegory is not widely found in early myth, some examples are attested in Homer, and allegorēsis of the same in Heraclitus. Prior to Heraclitus, Pherecydes of Samos (c. 570-495) was believed to have been the teacher of Pythagoras, and early allegorēsis is attributed to him though attested only in secondary sources.

…

Material evidence for extensive allegorēsis of myth in Hellenic thought is first encountered in the Derveni Papyrus (340-320 BCE), in a format said to reflect both the type of allegory and exegesis found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Alongside religious and eschatological teachings, it contains allegorical commentary on a theogony attributed to Orpheus, demonstrating a degree of sophistication that suggests an already developing tradition. The dating of the content (not the papyrus itself) coincides roughly with the earliest confirmed examples of allegorēsis in the sixth century BCE.

…

Plato was against allegorising myth as he feared it might reframe falsities as truths. Since Plato’s priority is to uphold “superior” philosophical discourse as a method for perceiving the world of intelligible Forms, the use of allegory would upend this. If some myths are true, Plato’s aim is to provide a parallel method for accessing the reality of myth without the flaws that characterise their dependence on unschooled narration and mimetic nature.

…

In contrast to Plato, Aristotle saw parallels between myth and philosophy and the practice of both: “even the lover of myth is … a lover of wisdom, for myth is composed of wonders.” Aristotle reconciles myth with philosophy by focusing on the commonalities between them.

…

The Stoic contribution to allegorisation of myth was crucial, and theirs was the only school of the Hellenistic era to explore it. Initially, they were certain that such interpretations were never intended by the poets or other composers of mythic narratives: the allegorēsis they applied was consciously independent of authorial intent. That they identified deeper meanings within otherwise “superstitious and ‘foolish’” compositions was irrespective of the fact that essentially poetry was to be “repudiated with contempt.” In part they followed Aristotle, considering that myths concealed the knowledge of earlier civilizations, but their readings were very different.

…

In short, the Stoics came to believe that myths became allegories accidentally, through a process of corruption. Though the early Stoics did not systematise a method for allegorical interpretation (this came later), they identified up to seven sources for traditional mythological narratives, and rather than attempting to shape the material to fit their theories, they applied etymological analysis to try to identify philosophical pearls amid the mythical stories. Later, etymological and allegorical analysis were combined, leading to theories that myths were indeed intentionally allegorical, in turn raising questions as to why this might be.

…

By the early Christian Era, allegoresis became more systematic and widespread. By late antiquity it had become so widespread a hermeneutic method that in essence it “rescued” ancient myth from obscurity or destruction. Regardless of the original intent of a text, this “new” method of unearthing hidden meaning equally sparked the production of new “wisdom texts… elaborating medial layers of reality and installing within them choirs of exotic divine and quasi-divine figures… [and] ontological genealogies.” Fragments, oracular statements, epigrams, archaeological and literary shards or wholly invented texts became prime targets for allegorical hermeneutics, and over time, so did aspects of dying languages - written or pictorial - whose original meanings had been lost.

…

A separate allegorising stream appeared with the advent of Christianity and influence of Philo of Alexandria, fused with Greek and Egyptian thought. Scripture, myth, and mysteries were seen as channels for divine revelation, used to promote the validity of Christianity. As Christianity spread and opposition to Paganism grew, the Neoplatonist school, with Platonic doctrine as their “theology,” sought to canonise ancient Greek theologies through allegorical readings as a bulwark against the advancement of Christianity. Sallustius’ On the Nature of the Gods attempted to harmonise Hellenic polytheist beliefs, while Iamblichus’ On the Mysteries synthesised diverse traditions.

The battle for Pagan survival was being fought in the intellectual realm: temples may be destroyed, but the preservation of “a tradition of thought and personal conduct as well as of cult” was the aim. Porphyry deliberately allegorised the Odyssey and Iliad to protect it “by means of allegory,” while launching a vehement attack on Christianity in his lost Κατά Χριστιανῶν (Against the Christians). Allegorical readings of both myth and sacred mystery are identified in Plotinian metaphysics, expounded in Porphyry, and spread among the Middle and Late Platonists.

Christian students of the fifth century are known to have read classical authors and their contemporary pagan opponents deeply in an effort to refute them; but simultaneously this quest “went hand in hand with the search for a way in which they could still profit from their reading of the classical authors while also pursuing instruction in their faith.”

Allegorēsis was used by both Pagan and Christian thinkers in the composition of penetrating apologetics and polemics for and against each other, in the effort to build ever stronger validation of their respective belief systems while demolishing their opponents.

However, the technique also had another vital role. Within the instability of this period, the adaptability of allegorical interpretation - the very flaw that Plato and others had identified - rendered it a powerful gift for the preservation of ancient myths, their texts, and commentaries.

Where Christian thinkers viewed Pagan material as heretical or dangerous, euhemerist or cunningly worded interpretations - even Christian apologetics - recast Pagan myths as little more than corrupt histories, or outdated poetry. Equally, incisive philosophical treatments allowed for the extraction and syncretisation of those elements that could be seen to foreshadow or support the case for the divinity of Christ, and these became absorbed into early Christian doctrine.

Dear Sasha, thank you for your service to the community. Blessings ✨🌿