Thar be Goblins! Part 1/4

Christmas Special on Greek Midwinter Magic

Please note this post will not be fully displayed in your inbox; click “read more” at the bottom or click here to view the full post in your browser!

Midwinter approaches, so welcome to a 4-part seasonal special covering Greek customs and magicoreligious practices throughout the festive season.

But first I must warn you about Greek Christmas goblins!

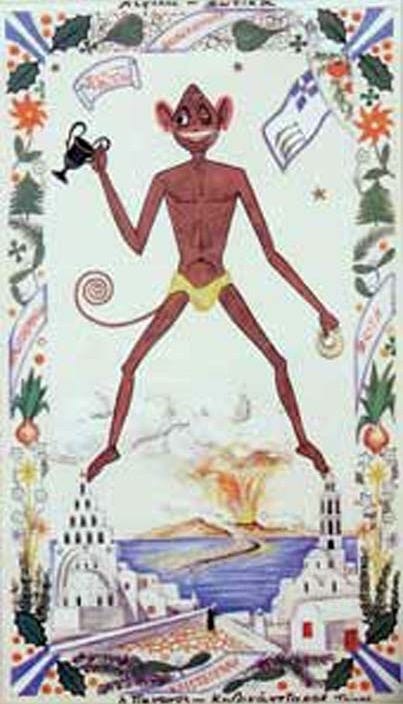

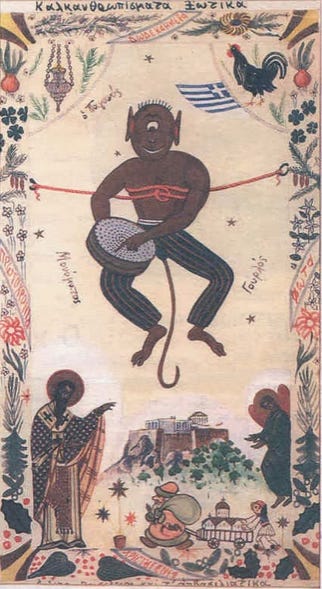

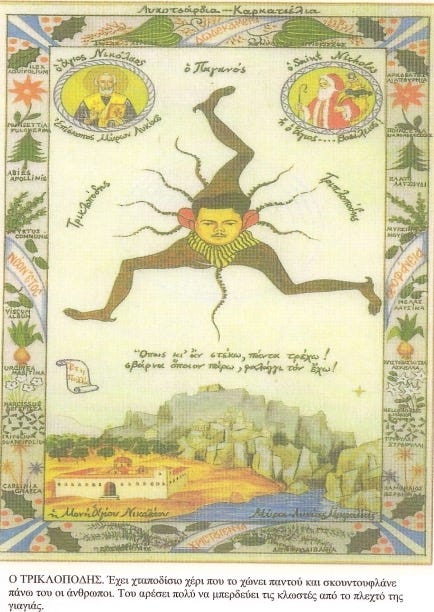

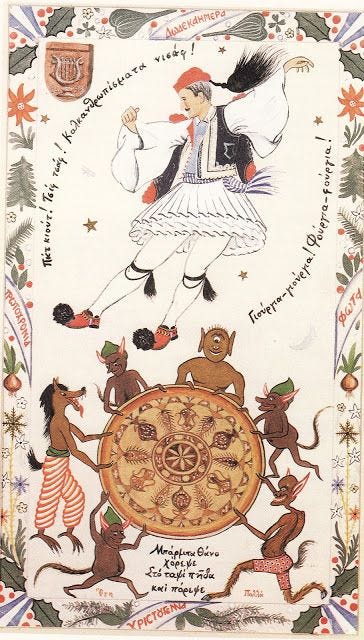

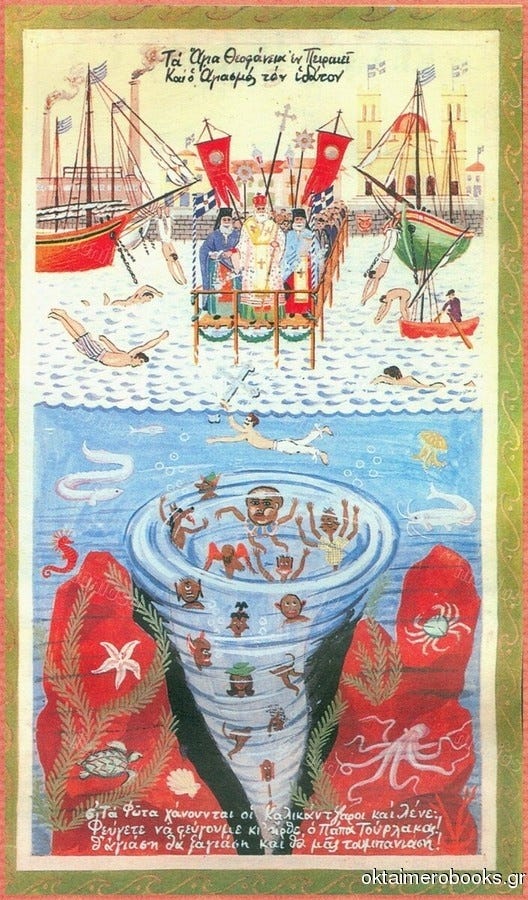

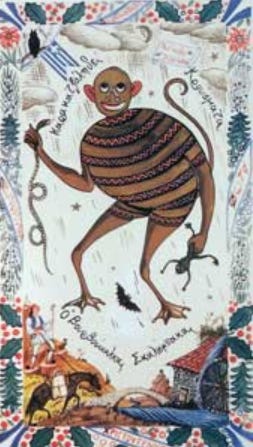

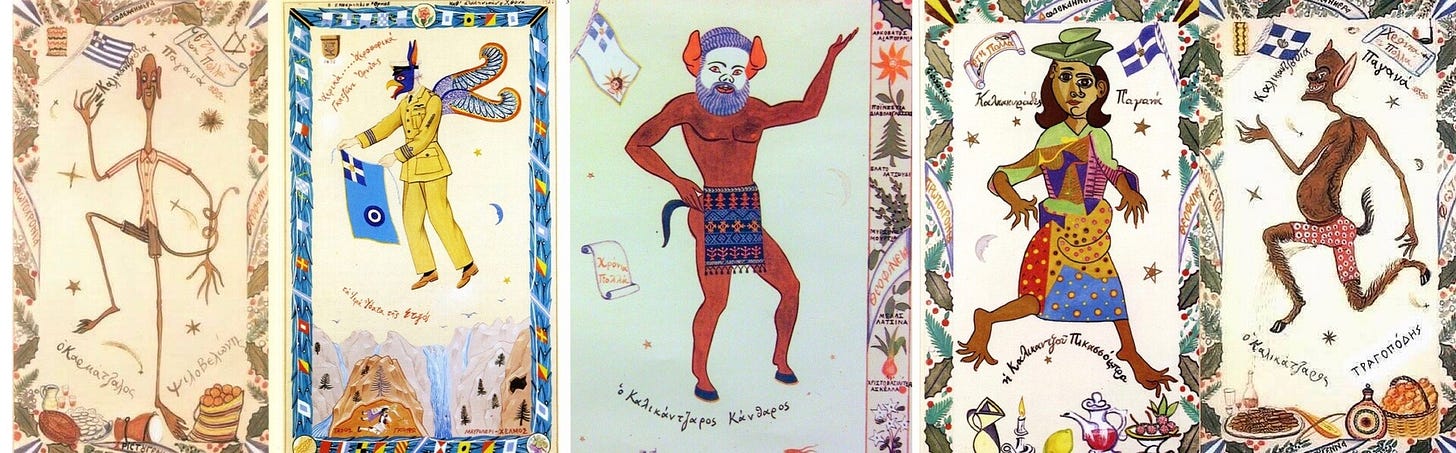

Greek folklore makes much of goblins - known as Kallikantzaroi (with localised variants on the name) - who cause havoc on Earth during the 12 days of Christmas. There are many traditions and beliefs surrounding them and how to protect oneself from them. They are said to return to the underworld on Epiphany, when the priesthood blesses all the waters in the land.

This is the first in a four-part series on the Kallikantzaroi, their origins, and their stories.

Here in Part 1 I have selected and translated (unabridged) a bumper collection of original wondertales about Greek Christmas Goblins, tying into a video recording available from Treadwell’s Events where I tell these stories as they would originally have been told: before the fireplace, having taken all precautions to ensure they don’t come down the chimney!

Hit play below to see the video trailer!!

I made it all by myself (with the help of some goblins!)

—> Sign up as a Friend of Treadwell’s to receive the full video narration and many more seasonal delights!

Disclosure: I partner with Treadwell’s to teach some of my courses, but I do not receive benefits from subscriptions. However, Friends of Treadwell’s do receive a generous discount on my upcoming courses.

Part 2 in this series explores the origins, names, and attributes of the Kallikantzaroi in folk legend, and looks at the magical ways to protect against them (including a recipe for purifying incense).

Part 3 looks more closely at Greek Christmas customs.

Part 4 focuses on the major feast of Epiphany, explains how goblins are banished anew for another year, and unfolds the deep magic in the ritual.

These instalments will drop weekly on Tuesdays until the New Year.

In between, on Thursdays, are more seasonal offerings: magical Christmas recipes and shocking hidden meanings in Greek carols.

Subscribe for free to receive them as soon as they are published. Please remember this is a reader-supported publication and I will be deeply grateful for your support. Each article takes days of research: every penny helps me continue devoting time to research to share here.

The wondertales

The following wondertales collected around Greece capture various stories about the Kallikantzaroi. Most of them have never been translated to English. I have selected them out of dozens to demonstrate regional variations on their mythos.

Please note that most of these are not suitable for children (obscenity, violence, offensive language). I know some readers are sharing these stories with their children: please read them yourselves first and judge what is age-appropriate for your child. The dark turn in some tales will be explored in the upcoming articles.

The last story is suitable for children; it is a literary version I included deliberately for this purpose. Written at the turn of the 20th century, it is the version most middle-aged Greeks (myself included) have grown up with. It is the main source of newer literary, artistic, and musical creations featuring Kallikantzaroi.

Enjoy, but look out for goblins!

This video features a very popular music album (1996) dedicated to the Kallikantzaroi and their antics by the Katsimihas brothers.

Though it is in Greek, the music should set the atmosphere for reading these. The spoken word element tells a version of the goblin stories.

Mandrakoukos

from Constantinople

Mandrakoukos, who is also called Gimp and Limpy, is the last in rank of the demonic hordes, and the first in rank of the Kallikantzaroi, thus their leader.

In appearance he is lame, stocky, with goat’s legs, a bald head, and he is ugly, monstrous! He also has a huge member (which is why we often call the member ‘mandrakoukos’).

Mandrakoukos comes out during the twelve days [of Christmas]. During the day he hides in quarries and remote areas, and at dusk he goes down to the crossroads and alleyways to find a woman, and mount her, and do all sorts of things to her. And if the woman knows how to exorcise the Unnameable One, she is released and can go about her business; otherwise she is in great peril at the hands of Mandrakoukos.

The Kallikantzaros

from Chios

Whoever is born in the week between Christmas until St. Basil’s Day (New Year’s) becomes a Kallikantzaros, and he is so possessed by the devil that he thinks of nothing other than how to harm others. During the twelve days [of Christmas] he goes out of his house at night, and wanders the streets as if hunted; he is wild and terrible, has long and terrible claws that he never cuts, and he rips people’s faces with them. For wherever he sees a human he mounts his shoulders and squeezes him until he’s half dead, and then he asks him: “Wool or lead?” And if he answers ‘wool,’ the goblin jumps off and leaves him and runs off quickly to find someone else to torment. But if he says ‘lead,’ then he squeezes him even harder and debilitates him, and rips him with his claws, and only leaves him when the person falls half dead upon the ground.

To keep the Kallikantzaros from thinking about these things and give him something else to distract him, during those days they give him a sieve, and tell him to count the holes.

He starts counting seriously and carefully, one, two… and once he gets to two, he can’t go further, because he thinks three is bad luck; so he’s always counting one, two, one, two… And if anyone who happens on him advises him to say three, he never changes his tune, but continues… one, two…

The Kallikantzaros doesn’t really bother anyone wearing new clothes, so that’s why they tease people wearing old and tattered clothing: “Put on something new, because of the goblins!”

To prevent a child born on Christmas Day from becoming a Kallikantzaros, their parents bring it to the marketplace where there is a fire burning, and there, holding it tight, they take off its shoes, hold its heels firmly and turn the soles of its feet towards the fire. They let its feet burn until it screams and cries and begs them to stop.

Then they move it away from the fire and cover its feet with [olive] oil and ointments and whatever medicines they know, to make the pain go away. And they say that when the fire burns and scorches the child’s toenails, then it can’t become a Kallikantzaros without toenails.

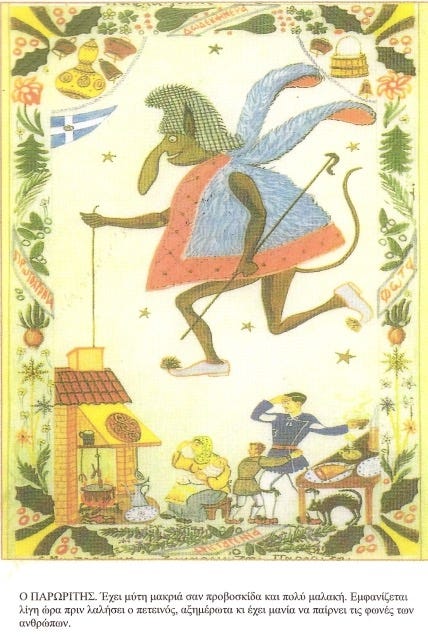

The Skalikantzeria

from Skiathos

The Skalikantzeria come to the villages during the twelve days [of Christmas] and leave on Epiphany eve. On Christmas Eve they come from far around and wait outside the village, and when day turns to night, they come inside. They’re evil and cunning, but they cannot hurt people, so even the women tease them and swear at them, and call them ash-foot, ashies, pissers, and many more names.

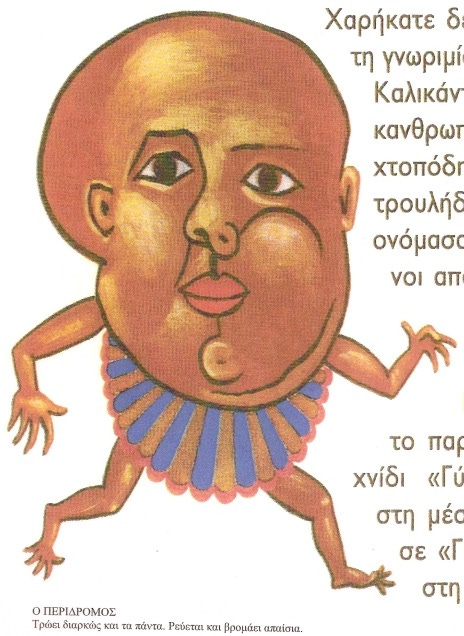

Each of the Skalikantzeria has a deformity, as do their animals. Some are lame, others are half blind, others have one eye, one leg, crooked mouths, crooked faces, crooked hands, humped backs, crooked bodies, and in short you can find all deformities among them. And just like them, their clothes are wretched, tattered, made of all kinds of rags. And so are the ornaments they put on their animals.

And even their behaviours and stance and everything about them is laughable and show that they’re very stupid and foolish. Say, one of them, yea tall, with long legs, rides a small rooster and his legs drag on the ground; another is small as a chickpea, and he sits up on a donkey so tall that when he falls off he can’t get back on again and calls for help; his donkey treads on the legs of the long-legged one, who screeches and threatens; and while they’re all tangled up, another one steps on them while trying to mount his one-eyed dog.

They eat worms, small frogs, snakes, and other such unclean things. And while one is eating, the other defecates in front of him. The first one gets mad, starts punching him, others too, shout and fight for all sorts of reasons.

And when they try to do any kind of job they can’t get it done, because they’re obstreperous, indecisive, one says yes, the other says no. When they start out to go anywhere, one runs while the other stays still, they fight on the way, and they can never get where they’re going, or they get there late. That’s why they can’t do much to humans, even though they’d love to.

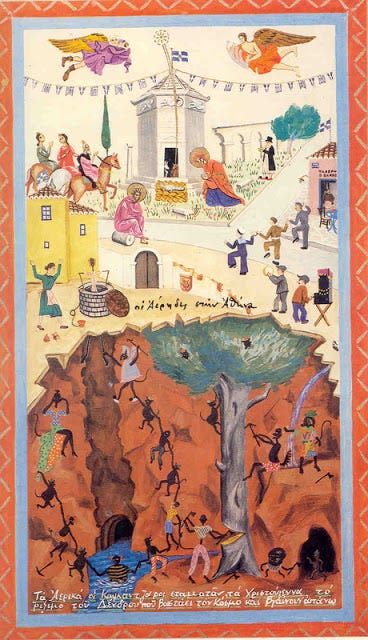

The Kallikantzaroi

from Dimitsana, Gortynia

The Kallikantzaroi are naked, without facial hair, and they’re as tall as a ten-year-old child, some a little taller and some a little shorter. They live in the Underworld, where there are three wooden columns holding up the whole earth. The Kallikantzaroi want to cut down the columns and destroy the world, so all year round, they take their axes and start cutting the three columns and they nearly manage it, when they hear that Christ is born, so they run and come up here to see him. And on Epiphany night, the Kallikantzaroi gather together and shout to each other:

Go, lets go

the crazy priest is here

with his censer

and his aspergillum (bunch of basil dipped in holy water)

and he blessed our arse

and our arsehole.

And they run away so they don’t meet a priest. And so they go back down to the Underworld, where they find the three columns solid again, and again they start chopping it all year round.

Once the Kallikantzaroi went to a miller, who was roasting a partridge and they caught its scent. They went to the door and saw him roasting it on a spit, turning it on the fire. They also caught some frogs, put them on little sticks to use as spits, and turned them outside the door to smoke them, but they saw no smoke.

They asked the miller to oil their frogs, like he oiled the partridge. The miller said: “oh don’t you worry, I’m going to smoke you”. They got angry that he was teasing them and wouldn’t oil their frogs, and they went up on the roof tiles and urinated to put out his fire, and then they ran down to see, had they put out his fire? But the urine had run under the stairs.

Once the miller had roasted the partridge, he fearfully shut up the mill, loaded his animal [donkey or mule] with two sacks, folded himself into the saddle and went towards the village. The Kallikantzaroi followed him; looking around, they couldn’t see the miller; and said: “There’s the one side, there’s the other, there’s the load [on the saddle], where’s the damn miller?”

They ran to find him at the mill, but they didn’t, then back to the animal, then back and forth, until the miller reached the edge of the village.

Then he shouted: “Save me, neighbours, from the Kallikantzaroi!” His neighbours came out with flaming torches and pursued them. Because the Kallikantzaroi are afraid of fire, and that is why at night they come down the chimneys and pee on the fire, or wherever they see ashes. That’s why the women don’t clear the ash during the twelve days of Christmas, and if they already have some they cover it, so that the Kallikantzaroi don’t go and soil it. And they clean the fireplaces and ovens after Epiphany.

The Karkantsaloi

from Gralista, Ithomi Municipality, Karditsa

The Karkantsaloi make their home in Hades, and grind their teeth on the columns holding up the heavens so they don’t fall and crush the earth. And as they keep grinding, they almost break the columns. They make them thin as the spindles that women use to spin with, but they feel stifled during the days of Christmas, so they leave them and go out into the world, and by the time they come back they find the columns as they had been before they started chewing on them. That’s how God made it happen, because the world would be lost if the sky fell and crushed the earth.

And when Christmas approaches they go out into the world, and wander around people’s houses, at night from Christmas until Epiphany, and then they leave. Don’t you know why the priests walk around on Epiphany Eve and light up the homes? To get rid of the Karkantsaloi, not for any other reason. Their leader is lame; with him and his one leg coming up ahead of the others who have two legs.

In the old days the Karkantsaloi were visible to humans; now we have become Karkantsaloi too because of our evils, and we can’t see them. And many have been harmed by them. Like Yiannis Pipiliagkos, God rest his soul. But everything that happened to him was on his own head, because he thought the things people do were foolish, like putting wild cherry wood on the fire, or old shoes, so the goblins don’t approach the house. On Christmas night, after the church bells rang, he went to church and lit two candles, and went back to his house to roast the pig that he had ready from the previous night. When he got home, he lit the fire and put the pig on to roast.

As he turned the spit, he saw a totally naked man come down the chimney (he only had a pointy cap on his head), with an iron spit holding a frog; and he went around the other side of the fire and the accursed creature began turning the spit to roast the frog. As he turned the spit he said to Yiannis “You pits, me pits!” Poor Yiannis nearly died of fright; he lost his voice, and he couldn’t breathe.

Then the accursed thing got up and peed on the roast pig, took the spit in his hand, and hit poor Yiannis over the head with it, fit to kill him. Then Yiannis jumped up and ran out of his house, and told his neighbours, and brought them back to his house. But they didn’t find the godforsaken creature. All they found was the spitted pig, and they buried it in the earth, in case some dog found it and ate it and died, for it had been peed on by a Karkantsalos.

And many other people have been harmed by them, but the antidote has been found, to make them vanish and not approach people’s houses. The antidote is the wild cherry and the old shoes, because if anyone puts those on the fire, the stench makes them steer clear of the whole neighbourhood.

The Skalkantzaroi and the kneading

from Leivadia

The Skalkantzaroi are tall, black, and hairy, they come during the twelve days of Christmas, and they come down chimneys into the house to contaminate everything; so at night people seal the jars of water and barrels of food, so the Skalkantzaroi don’t pee inside.

One night they went to the house of some woman, and shouted “Neighbour, neighbour, get up and knead the dough, for it is daylight” - and it was still before midnight - “we’ve started kneading and we’re lighting the oven.” Thinking it was her neighbour calling to her, the woman got up, poured some water, kneaded the dough, the loaf was ready, she lit the oven, put it in, and waited for dawn. What dawn?

The Skalkantzaroi shouted to her again, but just then the roosters crowed. Then they said, “Let’s go, the roosters are crowing.” The big Skalkantzaros said “We’re not going yet, they only crowed once.” But as he said it, they crowed again, then again, three times. Then the big one said: “Let’s go, a black cock crowed, and leave the neighbour or they’ll catch us.” That’s how she got away.

On Epiphany eve in the morning, people take the ash and spread it around the houses, so that the Skalkantzaroi go away and never set foot there again. The priest who comes to bless the homes gets rid of them, and then they say to each other: “Get up and let’s go, the priest is coming, the priest with holy water, and his wife with the aspergillum.”

The Kallikantzaroi

from Argos

Children born on Christmas Day become Kallikantzaroi if they are not christened on the same day.

Kallikantzaroi are swarthy, with red eyes, goat-legs, hands like those of a monkey and hair all over their bodies. They come during the twelve days [of Christmas] and enter houses through the chimney, but they can’t enter houses that have a pig-bone in the chimney, especially the ham butt. They love pancakes and New Year’s sweets, but they grab them very carefully, afraid of being hit with the wooden ladle.

They say that some of the Kallikantzaroi have a thorny cradle growing out of their back, and that’s where they put any children they snatch, and they rock them to make the children’s feet bleed, and they can drink the blood.

Except for Kallikantzaroi there are also [female] Kallikantzarines. Both male and female Kallikantzaroi strive to deceive people and take them to drown them in water or throw them off rocks.

Of one woman they say that she was tricked by a [female] Kallikantzarina, who appeared in the form of her neighbour, and took her to the sea, two hours away from Argos. She would have drowned her there of course, but at the last minute the woman realised what was happening and turned back and left. And the Kallikantzarina laughed and mocked her while she left, to goad her.

The Planetaroi

from Cyprus

The Planetaroi, who in some parts of Cyprus are called Kallikantzaroi, come to earth at Christmas and stay for the whole twelve days. Fey people can see them. Sometimes they appear as dogs, sometimes as hares, sometimes as donkeys and camels, often as balls of wool. The fey people trip over them, stoop to pick them up, but suddenly the ball runs off by itself. A little further away it turns into a donkey or a camel and keeps moving forward. The person is tricked, they get on its back, and the donkey then grows large as a mountain, and drops them from a great height, and the person goes home half dead, and if they don’t die, they will be sick for the rest of their life.

If, during the twelve days, someone can tie the Planitaros from the leg with red flax thread, he will become their slave, to send him wherever they want on difficult errands, and to order him to bring whatever they want. And anyone who ties up a Planitaros puts him near a sieve and orders him to count the holes; he counts one, two, but cannot proceed to three, because he is afraid of the Holy Trinity, so he falls silent, then begins again, one, two…

On the last day of the twelve, when the Planitaroi are to leave, they are looked after and they make them pancakes. And up at the top of the chimney, the [Planitaroi] go looking for the pancakes and sausages that they used to hang from the chimney, saying:

Titsin, titsin, sausage,

a piece of pancake

for Kallikantzaroi to eat

to go back to their seat

They throw the pancakes upstairs in the bedrooms for the Planitaroi to eat, and then they go from house to house waving goodbye as they leave.

Maro’s story

from Thessaly

To get rid of her stepdaughter Maro, her evil stepmother sent her to the mill to grind wheat during the Twelve Days, because she hoped the Kallikantzaroi would eat her.

Maro’s father took her as far as the mill, since he did everything his wife told him, and there he left her. Maro began grinding the wheat, and kept checking to see if she could finish before the Kallikantzaroi appeared; but she hadn’t even managed to get half the pit of wheat ground when midnight came. Outside the mill she heard shrill voices and a great hubbub that froze her blood in fear, and she fell flat on her face. The voices stopped, and she heard whispers; turning her head, what did she see?

The whole mill was full of Kallikantzaroi. They swarmed all over her and shouted at her in harsh voices: “Come bride, let’s dance!”

She didn’t lose her nerve, but to escape the Kallikantzaroi, she said: “Is this how a bride dances?”

“Well how does a bride dance?” they replied.

“She needs a silk dress,” Maro said.

The Kallikantzaroi disappeared on the spot, and soon returned with a lovely silk dress and said: “Here, come bride, let’s dance!”

“Is this how a bride dances?” she said once more.

“Well how does a bride dance?”

“She also needs a golden belt.”

They ran and brought her a belt. And to cut a long story short, she sent them on many errands, asking for more ornaments, and in the end she sent them to find her embroidered gloves.

The Kallikantzaroi took a long time to return, for it wasn’t easy to find such gloves in the village as they had found the other items, that they had stolen from houses that hadn’t lit the incense burners before their icons. And until they returned, Maro loaded the flour she had ground at the mill onto her beast. She put the one sack on the one side, the other on the second side, and on top she put the third sack and crawled and hid beneath it. The animal made for the village.

When the Kallikantzaroi returned to the mill, they didn’t find Maro, they ran to the back and saw the donkey, but not the girl. “Where is the bride?” they said. “This side, that side, and the top of the saddle. The bride’s back there!” and they rushed back to the mill.

As they ran to and fro, day broke, and the Kallikantzaroi hid in the nooks and crannies of the mill, only to emerge the following night which would be their last on earth.

When she reached the village, all the roosters, who knew what had happened at the mill, began crowing in delight: “Ko ko ko! There’s Maro with her gold, with her silver, ko ko ko!”

“Now Maro!” her stepmother said. “Now Maro is skin and bone!”

“Ko ko ko” crowed the roosters again. “There’s Maro coming with her gold and silver! Ko ko ko!”

And Maro entered the house, and told her stepmother what happened and how she tricked the Kallikantzaroi.

Mad with jealousy at seeing her stepdaughter with all those riches, her stepmother decided to send her own daughter, also called Maro, so she would come back with the same and more. So her father also took her to the mill, left her there, and the Kallikantzaroi came and said :”Come bride, let’s dance!”

“Is that how a bride dances?” said she.

“Well how does a bride dance?”

“She needs a dress of pure gold,” the other Maro said, “and golden shoes too, silk stockings, a diamond belt, diamond bracelets and earrings, golden plaits.” The Kallikantzaroi went off and soon returned with everything she had asked for, and because she couldn’t do otherwise, she put them all on, and the Kallikantzaroi grasped her wherever their hands landed, and began the dance.

They jumped to the sky, here and there, until they tore her to pieces, and whatever piece of her each had been holding, they then ate. Only her ear remained, and they fought amongst themselves over who would get it, until the Arch-Kallikantzaros told them to nail it to the wall.

The next day, the stepmother was awaiting her daughter, but in vain. She ran to the mill calling for her. “Maro, where are you, Maro?” Then she heard a voice from the foundations of the mill: “Now Maro! She’s skin and bone! A bit of her here, a bit of her there, and her ear on the wall.”

Her mother turned and saw her daughter’s ear nailed to the wall.

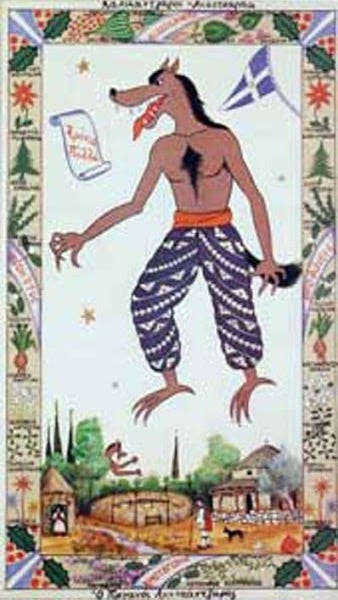

Ploumbo and Malamo’s story

from Ermoupolis, Syros

Many years ago in a village, all the village women had baked their Christ-bread from the night before Christmas Eve, except for one widow, who scrimped and saved and God finally granted her enough to buy some wheat, so she loaded it onto her donkey and sent it with her daughter Ploumbo to the mill.

When Ploumbo got to the mill, she called to Barba-Thanasis the miller to go and help her unload the donkey. She called and called, but in vain, Barba-Thanasis didn’t so much as whimper. Wasting no time, Ploumbo tied her little donkey to a tree and ran inside the mill. But what a sight!

Twelve wild creatures as tall as the ceiling, half human and half donkey, had tied the miller down and were beating him. When the girl saw them, she fainted dead away. The silly girl didn’t know she should say Agios o Theos [Holy is God] and the Kyrie Eleison three times as a weapon against the devil, to make them vanish in a flash.

On seeing such a beautiful girl, they ran to her directly, and brought her round, and fought over who should have her. The poor girl asked Barba-Thanasis for help, but he was tied up.

Soon all those wild things ran and brought her golden dresses, armfuls of gold coins, and dressed her as a bride and told her to ask for whatever she wanted, and they would bring in immediately.

The poor girl wanted nothing but to be taken home. So after they danced and danced, they put her back on her donkey along with the flour and started off to the wild mountains where their lairs were. These were the Lykokantzaroi [Wolf-Goblins], the devil’s own, and may God help her.

On their way they began fighting over who should have her first. “No I’m having her, no you’re having her…” as they fought, some fell behind and until they sorted it out, they sent all the lame and crooked ones ahead to Ploumbo. If they got too far ahead, those behind shouted “Oi, you, what’s Ploumbo doing?”

“There’s one side, there’s the other, and there’s Ploumbo in the middle,” they called back.

But as they called back and forth, Ploumbo slowly slipped off her donkey, placing her jacket upright between the two sacks, and hid behind a tree.

Once the girl saw they had moved on, she came out from behind the tree and staggered home along another path, half dead with fear. She cried to her mother:

“Mother, open up, open with two torches in your hands!”

She told her mother to get torches, for the Lykokantzaroi are very scared of fire. Her poor mother ran out with the torches and saw Ploumbo dressed head to toe in gold. She was dripping gold coins, and after urinating on them so they wouldn’t turn to coal, they put crosses and talismans behind the door so that the Lykokantzaroi wouldn’t come down the chimney.

Meanwhile, they were still fighting over who would have her first. And once they got to Miglaina’s garden, they stopped to get her off, they looked here, they looked there, but there was no Ploumbo. After searching and searching, they started beating up the lame and crooked ones who should have been guarding her. But as they were being beaten, they kept screeching:

Ploumbo here, Ploumbo there

Ploumbo in the sack!

To be certain that she really wasn’t in the sack, they poured the flour on the ground, and off they went.

Soon Ploumbo’s mother asked her neighbour for a scoop, and shovelled the gold coins into a chest. When the neighbour heard the whole story, she sent her own daughter, Malamo, to the mill, in the hope she would also be gifted gold. So she too, loaded her donkey with wheat, and went straight to the mill.

When she got there, the Lykokantzaroi ran out in delight and grabbed her to relieve their frustration. First they asked her what she wanted them to gift her. She asked for the starry sky, the sea with all its ships, and the earth with all its flowers. When the Lykokantzaroi heard everything she asked for, they didn’t waste any time.

They slaughtered her donkey, stripped her naked and dressed her in its skin, and hung its guts around her neck instead of gold coins.

When she got home, her mother washed her, but she never washed clean.

The Kallikantzaroi

Version by Andreas Karkavitsas (original edition 1898; reworked 1922)

“Come on, quieten down you little devils!”

“Yiannis, Yiannakis - a piece of meat…”

Yiannakis the son of Mr Nicholas the miller was in deep despair. Wherever he turned his eyes, wherever he reached out his hands, all he touched were Kallikantzaroi. They were so tiny, like walnuts, with long beards, and goat’s legs, and tall pointy caps on their heads. They swarmed all over the floor of the mill; if you dropped a needle it wouldn’t reach the ground.

The miller’s son was roasting pork on the spit and as the fat dripped on the coals it smoked and smelled so good as to make you tremble with hunger. Of course the greedy little devils couldn’t control themselves and their tiny, coriander-seed eyes lit up like the coals on the hearth. At least they sucked the fat, but what of the Kalikantzaroi?

“Yianni, Yiannaki - a piece of meat!” they kept begging, clinging to Yiannakis like ticks.

“Come on, quieten down you little devils,” he’d say, soothingly.

And to get them off his back, every so often he’d take a half-roasted piece of meat off the spit and throw it into the swarm! They would lunge at it, trampling each other over the meat, howling, thrashing, biting until the piece found its way to the insatiable stomachs of a lucky few lucky. Disgruntled, the others threw themselves at Yiannakis again, pinching and swarming all over him. And he would throw another piece and then another until the spit was nearly empty and the miller’s son starving.

His father had become unexpectedly ill and had left the mill at dawn. Yiannakis remained in his stead to finish milling, loading and offloading all day long. He dragged the wheat from the donkey’s back to the pit of the mill, and back again, throwing the warm flour into the sacks and loading it onto the animal’s back. The boy had not found a moment to rest all day long. He wasn’t even able to eat properly until nightfall. And just as he thought his labours were over, the Kallikantzaroi swarmed in and wanted to play games.

Where did they find the energy? But then, why shouldn’t they? It’s not as if they’d ever worked in their lives. Had they ever laboured for a loaf of bread? They lie around all day in caves, satiating themselves on the lizards and snakes that good fortune sends their way, and they come out at night to play and torment humans. What a great life!

And Yiannakis racked his brains for a way to convince the little devils to let him eat.

“Hey, boys, let me tell you something,” he said gently.

“The half-grown pumpkin-cheeks wants to tell us something!… The half-grown pumpkin-cheeks wants to tell us something!” the Kallikantzaroi babbled all at once.

And they gathered around him, climbed on his knees, rappelled onto his shoulders, others hung themselves off his stubble and short hair, and for a moment they totally covered him like mice on a docile kitten. They cackled to each other like geese; they pinched his bare skin pretending to caress him; they bit him pretending to kiss him, and trits prits! trits prits! trits prits! they rumbled and farted unabashedly, making the mill stink of garlic.

You’ll become a priest at this rate - such is this curse; Yiannakis thought to himself. Since he found himself alone at the mill, he would have to endure all of it. There was nothing he could do. Besides, he knew well that the Kallikantzaroi only roam the earth during the twelve days of Christmas, when they want to torment humans. For the rest of the year they’re in the guts of the earth, chopping at the Tree of Life that holds up the world, with an evil plan to destroy the world. They chop and chop until Christmas Eve, and only a thin strip is left. But then they leave it and come up to the earth to enjoy the freedom to tease humans given them by the Almighty. They know that when they return, they will find the Tree regrown and begin all over again.

But they do leave the tree; for their joy at tormenting humans is greater. And how long will their dominion last, thought Yiannakis to himself. Tomorrow they’re blessing the waters and at dawn the demons will scatter in fright and go back to hide in their caves. They only have a few hours left. So he had to find a way to endure those hours as best he could.

“Well quieten down so I can tell you!” he said with a smile, plucking a few of them off himself carefully.

“Come on, tell…”

“Sit on the ground first.”

A loud thump was suddenly heard, as if a balloon had popped, and all the Kallikantzaroi suddenly landed on the ground. As they curiously awaited his words looking attentive, the miller’s son carefully took pieces of meat off the spit and wolfed them down.

“Come on, will you tell us?” several of them said impatiently.

“Oi, you, will you tell us?” said Bakakas angrily.

This Bakakas (frog) is like a little old man with a white beard, two fathoms long, and a baby Kallikantzaros hangs from every hair, like dates on tall branches. When he walks and his white beard drags on the ground, the baby Kallikantzaroi hop higher up and look like fish jumping in a net. He holds a thin staff - his sceptre - and this makes his companions respect him.

Yiannakis realised he could not fool the cunning Bakakas for too long, and decided to speak. But he couldn’t because his mouth was stuffed with food, and he was in a hurry to swallow the scorching meat burning his mouth. And the more he hurried, the more he nearly choked, and widened his eyes like 5-drachma coins.

The old one worked out what was happening and gestured angrily to the company. They swarmed the spit like maniacs, grabbing the meat, strewing it on the floor and began stomping stubbornly all over it.

“Tritsi prits… tritsi…prits!“ they went, mocking and laughing at Yiannakis.

Yet the miller had managed to eat a little, and though he was still hungry, it held him together. He wasn’t too bothered about this. He was angrier at their dirty games, and in his anger, he grabbed a burning torch and dropped it in their midst.

Tritsi prits… tritsi…prits… tritsi…prits!

They all scattered here and there like a herd of sheep catching sight of a wolf. The Kallikantzaroi are afraid of fire. They have never forgotten what the cunning old woman did to them, not so long ago. She tricked them, shut them into a little barrel, and burned them alive. And why? Because the accursed creatures went and shamed her daughter while she slept. They got her pregnant and since then the Kallikantzaroi have been in the world…

However, Yiannakis had begun thinking in earnest how to escape from them. It was very late at night; soon the eve of Epiphany would dawn and he had to take the flour home for them to bake bread. But how could he escape from the demons?

“Boys, shall we dance?” he suddenly asked, jumping to his feet.

“Yes, dance!” they all said eagerly.

And they began shaking their spindly spider-legs, some raising their arms, shouting hoarsely, whistling, and a small one grabbed a rag from somewhere and shook it as if it were a scarf.

“Not inside,” Yiannakis said. “Outside, under the little moon.”

“Yes, outside!” they all agreed.

And they swarmed outside and filled the yard around the mill. The moon was at its peak; the morning stars shining bright on the horizon. The wind that had blown wildly all night, shaking the trees, had chased away every cloud from the sky. In the distance the mountains circling the broad plain were clear to see. The fresh leaves glinted with the dawn dew.

The Kallikantzaroi and the miller’s boy danced and danced. Their shrill voices became one with the night birds and crickets.

“Hey, boys, the horse is neighing,” Yiannakis said suddenly. “Let me check on him and I’ll be right back.”

He rushed into the mill, loaded two sacks of flour onto the horse, climbed inside another sack and threw himself flat on the saddle. “Shoo!” he went, and exited through the other door with his horse, heading for the village.

But the Kallikantzaroi were so in the mood for dancing, that they didn’t even notice he was gone. One after the other took the lead and danced like maniacs, singing loudly:

The mud and cowpats dance

And the goat’s droppings too;

The old ragged clothes dance

with the old ragged rug!…

“Hey, what happened to the miller?” Bakakas suddenly exclaimed.

“Yes, the miller! Where’s the miller!” the others asked each other.

Some ran to the mill, looked in all the sacks, searched in the pit, looked in the stream, even under the millstone, but Yiannakis was nowhere to be seen.

“He’s gone!” they said, looking at each other in surprise and rage.

“What shall we do?”

“Let’s catch up with him!” Bakakas ordered angrily.

In a flash they all poured forth like a whirlwind, trampling the mud with cries and noise, like a babbling pack of jackals. Soon they caught up with Yiannakis’ horse that was heading for the village at a steady pace. They surrounded the horse and looked for the miller.

“There’s the one side, there’s the other, and there’s the top, but where’s the miller?” they asked each other in frustration.

“He must be back there,” Bakakas said. Clamouring, they immediately rushed back, cantering like wild foals. They searched the whole road leading to the mill, the ditches and bushes, they even lifted up the rocks, but they didn’t find Yiannakis anywhere. Then they went back to the horse that was quietly walking on its way, and began searching in earnest.

"There’s the one side, there’s the other, and there’s the top, but where is the damn miller?” they muttered to each other.

“He’s gone on ahead!” Bakakas cried out angrily.

Now they all ran forward, searching the road up to the first houses of the village.

Meanwhile, tucked in his sack, despite his fear Yiannakis couldn’t help laughing as he watched the Kallikantzaroi run to and fro. Sometimes he’d raise his head fearfully and impatiently look ahead to catch sight of his village. Finally, as the first rays of gentle dawn broke, he saw it, with its many mulberry trees and little white houses.

“Wood, logs, burning torches!” he immediately shouted at the top of his voice.

The Kallikantzaroi turned and saw the village too. They were chilled with fear and stood speechless for quite some time, silenced where they stood, as if nailed to the spot. At that very moment the first crowing of the rooster was heard from the village - “Koukoukoukou!…”

“Let’s be off!” said Bakakas bitterly, when he saw Yiannakis laughing at them astride his horse. There is no more work to do in this world, the humans got one over on us.

And raising his staff like a banner he led the way, and the others followed him shouting:

Leave, let’s leave,

for the crazy priest is here

with his aspergillum

and with his cloth.

He wet us, he blessed us,

and he burned our bottoms!

Trits prits! trits prits! trits…prits!

About these wondertales

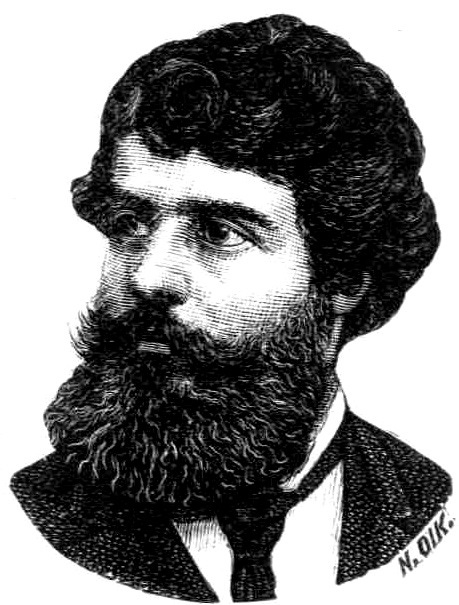

In the late 19th century, Greek folklorist and philologist Nikolaos Politis systematised early folklore collection and study in Greece by recruiting teachers, doctors, and priests from around the country and asking them to record the wondertales told in their region, complete with regional dialect. He wanted all possible expressions of traditional folk life: oral tradition (songs, proverbs, blessings, narratives etc), descriptions of social organisation, everyday life (clothing, food, household), professional life (agricultural, animal husbandry, seafaring), religious life, justice, folk philosophy and medicine, magic and superstitions, folk art, dance, and music.

He gathered these artefacts of Greek folk life and applied ethnographic and comparative methods of his day to their study. Politis published comparative studies in relation to other Balkan nations as well as to the myths and histories of antiquity. Though his methods were relatively simplistic and are now outdated, his collections form a valuable corpus of records and have been exhaustively studied by later scholars as the field in Greece became more sophisticated.

In this series of snippets, I aim to translate a handful of his most interesting or amusing stories since they have never been translated into other languages. They are presented as-is, with minimum commentary where it is needed for context. Many of these deserve commentary and analysis; this will form the topics of longer-form article in due course.

Read more about why they’re called wondertales in the first section of my article here.

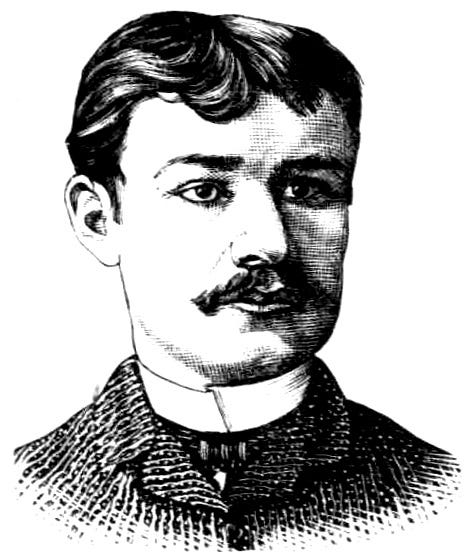

About the last tale

This version was written by Andreas Karkavitsas (1865-1922), a much-loved Greek novelist who contributed greatly to disseminating these tales among the new Greek reading classes throughout the 20th century. It is mostly his versions that today’s Greeks are familiar with, even if they’re not aware of it (myself included).

Karkavitsas was an army doctor whose greatest passion was storytelling, and he wrote prolifically for newspapers, publishing novelettes and short stories based on local folk tales. Especially towards the end of his life, he became a member of Nikolaos Politis’ (see above) Folklore society and drew upon Politis’ collection of wondertales for material.

A literary naturalist in a similar vein to Émile Zola, Karkavitsas enjoyed portraying folk life in all its grimy detail, providing valuable snapshots of the authentic lives of villagers, seafarers, grifters and fishermen at the turn of the 20th century. Only one of his collections of short stories has been translated into English. These stories are now in the public domain, and this is the first English translation of his material (that I know of). More on Karkavitsas.

Look out for Part 2, about the Kallikantzaroi, their origins, attributes, and their place in Greek folklore; Part 3, about Greek Christmas customs, and Part 4, about how to banish goblins for a year.

Also coming up: A Christmas magic recipe special, and the Secrets of Greek Christmas Carols involving a fortune-telling squid!)

More collections of wondertales on this website

Find the other parts of the Christmas Special series here:

Part 1, a bumper collection of Greek Kallikantzaroi wondertales;

Part 2, about the origins, attributes, and place of Kallikantzaroi in Greek folklore;

Part 3, about Greek Christmas customs

Part 4, about how to banish Kallikantzaroi for a year.

Also see my special features on Greek magical cooking and carols!

Excellent read. I'd never heard of these little pests before. Now I have to read the rest of the series because I'm a huge nerd for folklore. Thank you!!