Halloween Special: The Undead and the Devil

Greek folk horror stories

These folktales are direct translations from authentic Greek folklore collections. The stories were recorded from oral retellings in the late 19th century. I have not edited nor added to them; they are presented “as-is.” Scroll to the bottom to read more about the source.

1. The Undead and the Devil (from Zakynthos)

A vrikólakas (revenant) stood outside a chapel every night. All night he would run a little way, and then stand outside the church. But he wouldn’t sit down. Sometimes he had his head in the grave where they’d buried him, sometimes he had his feet in the grave and his body outside, and he’d shout that the demons were squeezing his feet. Nearby there was a demon’s nest, and he’d come out and beat up the revenant.

Someone saw the demon telling the revenant to mow the fields of a bad landowner and set it on fire; someone else saw him digging in the earth with his nails while the lame demons beat him.

This man who became a revenant lived a thousand years, and God is still punishing him, because he lay in ambush one night, and hit a good man and left him dead on the spot. After a while, a lightning bolt fell and took his sight and drove him mad. Shortly afterwards he died, and they buried him in the same place as where he killed the man.

And God ruled that he should always be tormented, and should himself torment bad people, and the demons should guard him where he struck the blow, and that should be the place of his torment.

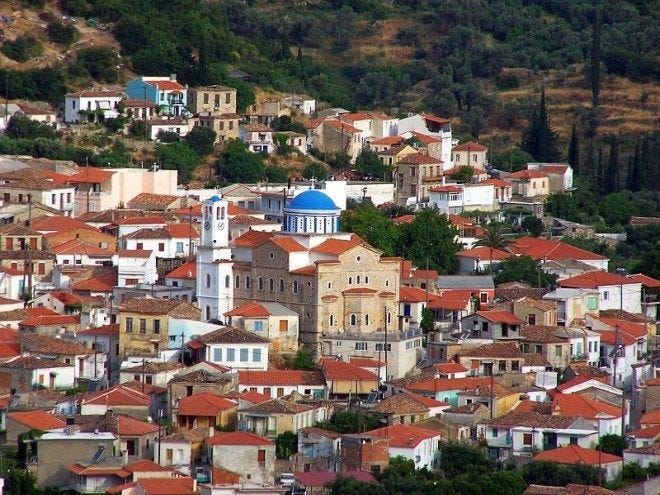

2. The consecration of the graveyard (from Samos)

In the village of Pagonda there were many revenants, and to escape this evil, the villagers called a goēs (γητευτής) and each gave him a silver coin to consecrate the graveyard. He took three bull triplets (born at the same time from one cow) and circled the graveyard three times, saying some magic words.

That way he consecrated it and nobody rose from the dead again. And not only that, but many come from the coast across the water (in Turkey) and take some dirt from the Pagonda cemetery and take it to their own cemeteries so that those they stick in the dirt there don’t become revenant, and some put the dirt into bags and hang it on the walls of their homes as talismans.

The goēs (γητευτής) told the villagers that if they wanted him to, he could consecrate the whole village so that exotic or other malformed things would not enter. He asked them for three silver coins each. But they thought it too much, and so did not do it.

3. The revenants of Gralista (now called Ellinopyrgos) (from Karditsa)

Revenants come from the dead (may God protect ordinary people from these adversaries!) because sometimes there is a sinner, and he becomes a revenant, and he comes out of his grave at night, and he goes to his relatives’ houses and eats anything he finds; flour, butter, cheese, whey, meat, he drinks water from the jugs, and whatever else.

In the morning, anyone who eats of that flour, or butter, or anything else this enemy touches, they die in forty days, and they also become undead, and then, because people are like sheep, they stampede and desert the village. At night revenants look like fire. And I and many others have seen such fires coming out of the graves.

Once, not so long ago, there was a sickness in our village, and many people died, both men and women. Poor old Tselios died, and Rentzakina, and others. These two, Tselios and Rentzakina - may God forgive me - were sinners, what they were I don’t know, but they became revenants. But God willed it and stopped the evil. Because when we saw the fires at night, we told everyone in the village the next morning.

The following night, poor old Thanasis Gogos, a clever man, ordered us to go out again with shotguns, and we stood watch and observed carefully to see what these fires were, and whether they were fires or fireflies, and we truly saw they were vampires; because we saw the fires coming out of the graves, and walking straight, one to Tselios’ house, and one to Rentzou’s. We were very frightened that they would do something to us, so we all started muttering “the donkey’s in the garlic patch” because these words scare them and they don’t approach people.

In the morning in the village we told each other what we had seen that night. While we were discussing what to do, Tselios’ widow came over and said that on the pail with the flour, she found human fingerprints. When we heard this from the widow, we were very scared and didn’t know what to do. We lost our minds, and nobody knew how to interpret this, how to strike back at this evil that had found us.

Then poor old Papargyris, as if suddenly enlightened by God, told us to send for old [priest] Papagiannis from Kanalia [village] to make the sign of the cross over the graves, to make talismans for the people, so they would not be lost to the revenants.

So immediately we sent a runner to Kanalia and brought old Papagiannis, a man with a blessed soul, an old man of a hundred and ten years, who knew many things. He came on Friday night, because he wanted to begin the war on the vampires on Saturday, because on Saturdays they are sleepy, and they have no strength.

All night he made crosses out of vines, and on Saturday morning he held a service, and after the service he went with the other priests and all the villagers to the graves, and they opened the two graves of Rentzakina and Tselios. And what do you think we saw? The dead were swollen, like drums that can hold twenty loads of grapes.

Then old Papagiannis put on his stole, and he read and he read over there, for nearly two hours. And then he hit them forcefully in the belly with his crutch; his crutch had a finger’s width of sharp iron on the bottom, and he pierced their bellies. And what a rumble they made, imagine, like a ball [bursting]!

Then he put three crosses upon each of them, one on the head, one on the chest, and one on the feet, and then they closed up the graves. Then he gave a cross to each villager, to keep on their persons to protect them from the undead and every evil. That’s how the people escaped then.

Many villages were ravaged by those adversaries, because they didn’t catch the evil in time as we did. See, that’s how Agia Marina, Primbei, Paliochori, and other villages were lost.

Some say they were lost to the plague, but they don’t know anything. I went to those villages, I did, and as a slip of a boy I was with the Armatoloi [militia of the Greek War of Independence] of Karaiskakis, and I know the truth of how they were ravaged, and what others tell you are fairytales.

* Written in local dialect

Nikolaos Politis, Traditions: Studies on the Life and Language of the Greek People, Athens, Historical Publications, 1904; trans. by Sasha Chaitow © 2024

About these folk tales

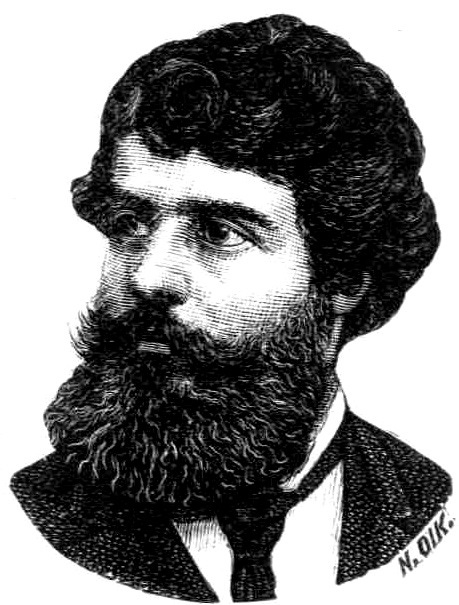

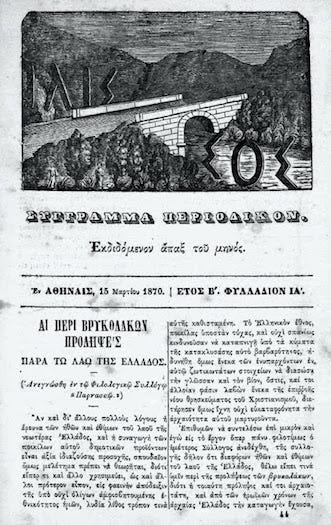

In the late 19th century, Greek folklorist and philologist Nikolaos Politis systematised early folklore collection and study in Greece by recruiting teachers, doctors, and priests from around the country and asking them to record the folktales told in their region, complete with regional dialect. He gave instructions for the speech to be recorded as faithfully as possible. He wanted all possible expressions of traditional folk life: oral tradition (songs, proverbs, blessings, narratives etc), descriptions of social organisation, everyday life (clothing, food, household), professional life (agricultural, animal husbandry, seafaring), religious life, justice, folk philosophy and medicine, magic and superstitions, folk art, dance, and music.

He gathered these artefacts of Greek folk life and applied ethnographic and comparative methods of his day to their study. Politis published comparative studies in relation to other Balkan nations as well as to the myths and histories of antiquity. Though his methods were relatively simplistic and are now outdated, his collections form a valuable corpus of records and have been exhaustively studied by later scholars as the field in Greece became more sophisticated.

In this series of snippets, I aim to translate a handful of his most interesting or amusing stories since they have never been translated into other languages. Many of these deserve commentary and analysis; this will form the topic of longer-form articles in due course. In these posts the translation is presented as-is, with only the lightest of edits for readability, and links to words or place-names that may need context.