Why Byzantine Scripts Look Like Secret Code

Renaissance Wisdom Revealed: What Dürer Really Encoded in Allegory of Philosophy (Thyrathen Fragments)

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

Introducing Thyrathen Fragments

Welcome to the first of the Thyrathen Fragments: a new series of case files, each offering a close reading of a single subject: a saint’s curious journey, a contested ritual, a single image, a particular figure, or strange event.

Where my research essays and Crossroads series (a cross between investigative journalism and misinformation debunking), offer a wider lens, Fragments keep the focus tight: one case, properly examined, with just enough context to show why it matters.

We begin with a double article about a script that has left papyrologists squinting, trainee historians sweating, and more than a few occultists convinced it hides forbidden wisdom.

Why does Byzantine handwriting send even the boldest scholar running for a specialist? And what happens when it surfaces in the heart of Renaissance art?

In this first Fragment, we decode what Dürer really inscribed in his Allegory of Philosophy; and why it matters more than most imagine.

A friend recently sent me an image, asking if I could help decipher what he saw as "symbolic writing" in the background. He'd guessed at various esoteric provenances - was it alchemical notation? Some kind of cipher? When I told him it was simply Greek written in Byzantine minuscule cursive, his response stopped me cold: "I didn't even realise it was Greek."

The image was Dürer's Allegory of Philosophy (1502), where the German master had carefully copied Greek text into his woodcut. My friend, highly educated and culturally literate, couldn't recognise Greek when it wasn't in the tidy capitals of classical inscriptions. Another colleague recently asked for help with an early modern print typeface; which was literally “all Greek to them.”

This crystallised something I've been observing in Byzantine and Classical studies: how thoroughly we've managed to make the familiar seem alien, and the living seem dead.

This isn’t just anecdotal. It’s part of a larger pattern in how Greek tradition is represented.

It’s fashionable to call Greece the “cradle of Western civilisation”—a claim repeated so often it’s rarely questioned. But even the Vatican’s own digital handbook on Greek paleography calls this idea “problematic,” pointing out that what we now label “the West” is actually a patchwork of elements from many times and places.

The Great Lowercase Revolution

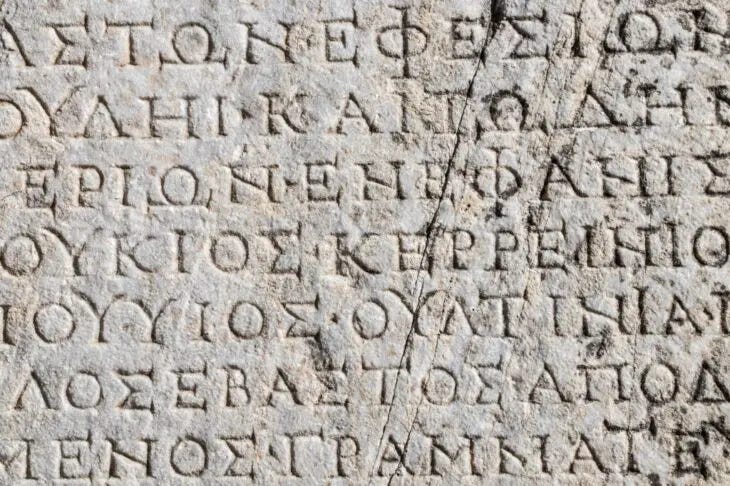

To understand why Byzantine Greek looks "mysterious" to modern Western eyes, we need to start with a simple fact: ancient Greek was originally written in what we call majuscule - all capitals, no spaces, like this: ΚΑΙΕΙΠΕΝΟΘΕΟΣΓΕΝΗΘΗΤΩΦΩΣ.

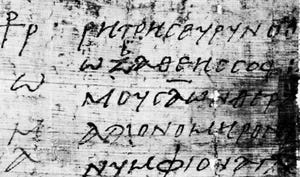

This style reflects the tradition of Greek inscriptions and was used for papyrus manuscripts dating to the Hellenistic period (300 BCE and earlier), especially in Alexandria, where scribal circles refined a rounded, formal majuscule that later appeared in the great biblical codices of late antiquity.

In Greek paleography, majuscule covers all the ancient uppercase scripts, while uncial refers specifically to the rounded, formal book hand that dominated manuscript production from the 3rd to the 9th centuries CE.

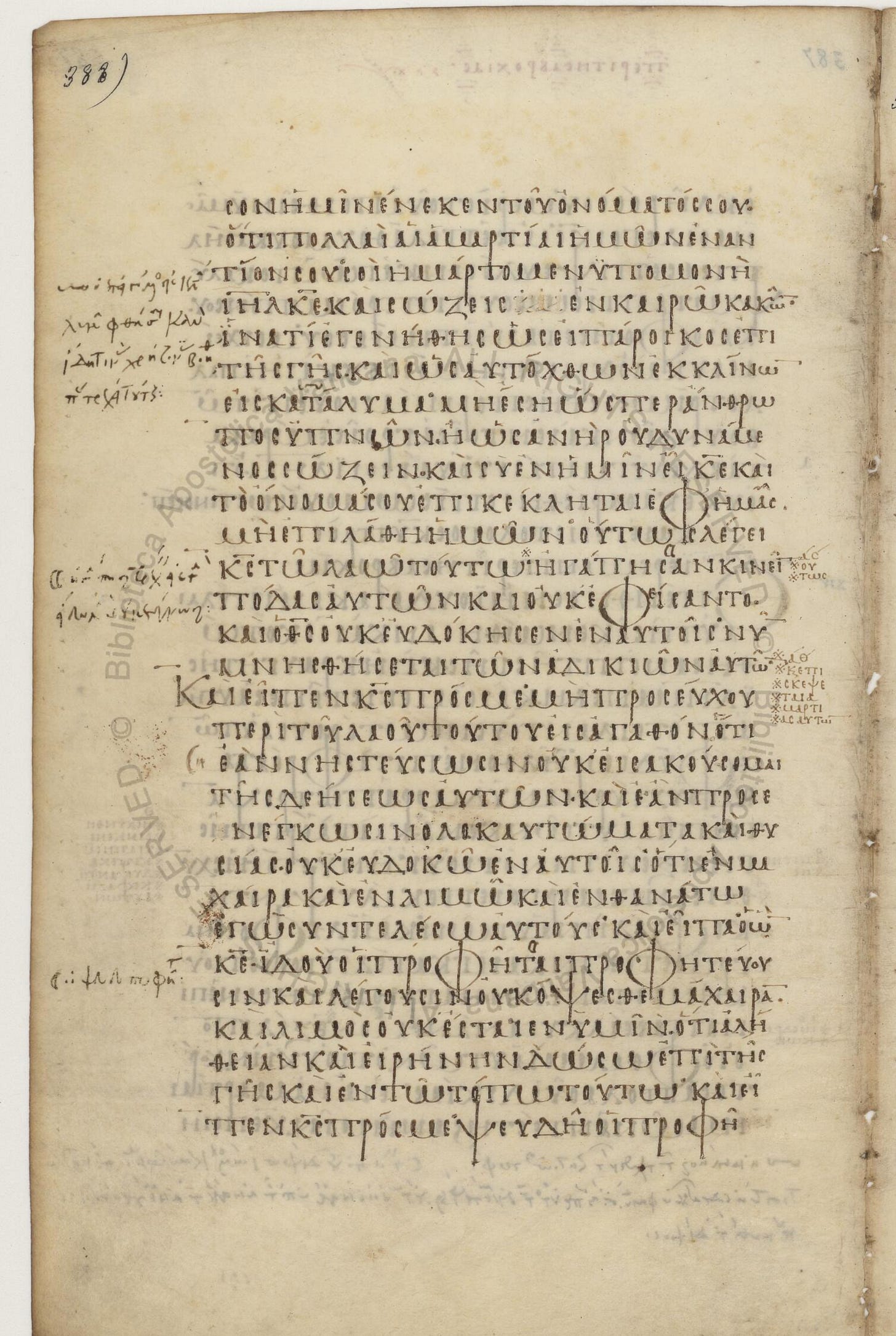

By late antiquity and into the Byzantine era (4th–6th centuries CE), two distinct parallel scripts emerged. Uncial, used for formal book production in majuscule style, persisted in sacred and literary manuscripts. Meanwhile a quicker, cursive hand developed in everyday writing—on documents, letters, and less formal texts—with slanted, interconnected forms and early ligatures.

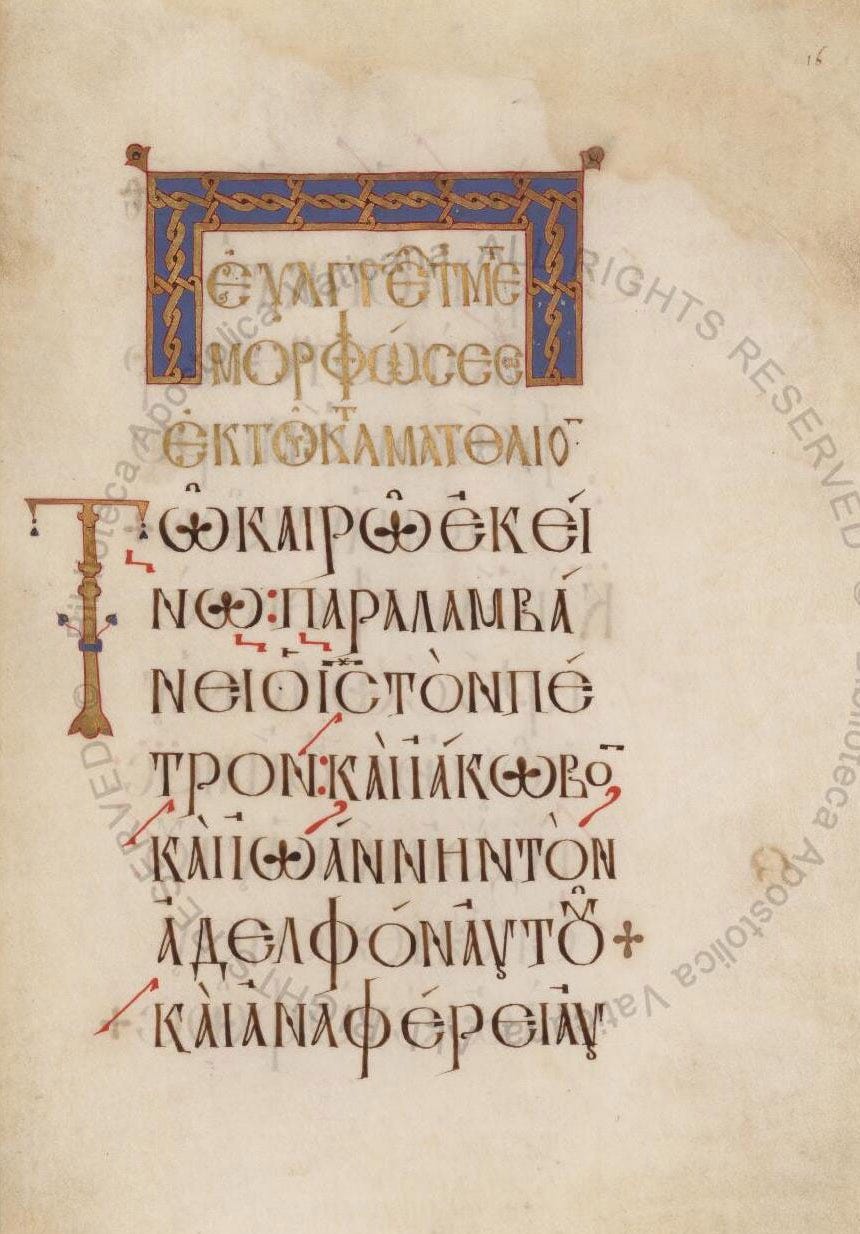

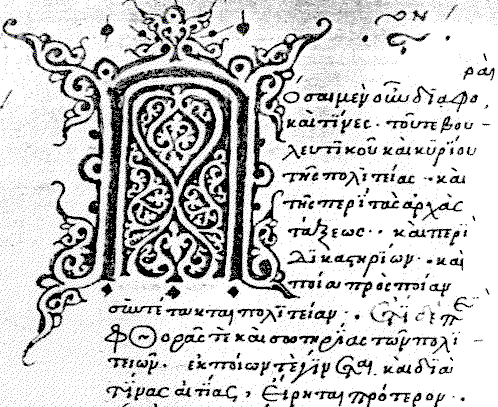

The full-scale transition came in the 9th century CE, when Byzantine scribes introduced minuscule: a compact, rounded, and connected form of writing based on earlier cursive forms. It also incorporated word-spacing, accents, and breathing marks. This minuscule quickly became the standard book-hand, and most older works in uncial script were recopied in this new style—rendering nearly all prior majuscule manuscripts rare compared to later copies.

This represented a technological revolution. Minuscule developed out of Byzantine cursive in which scholars composed epistles to each other, allowing scribes to write faster, fit more text on expensive parchment, and develop a more efficient book culture.

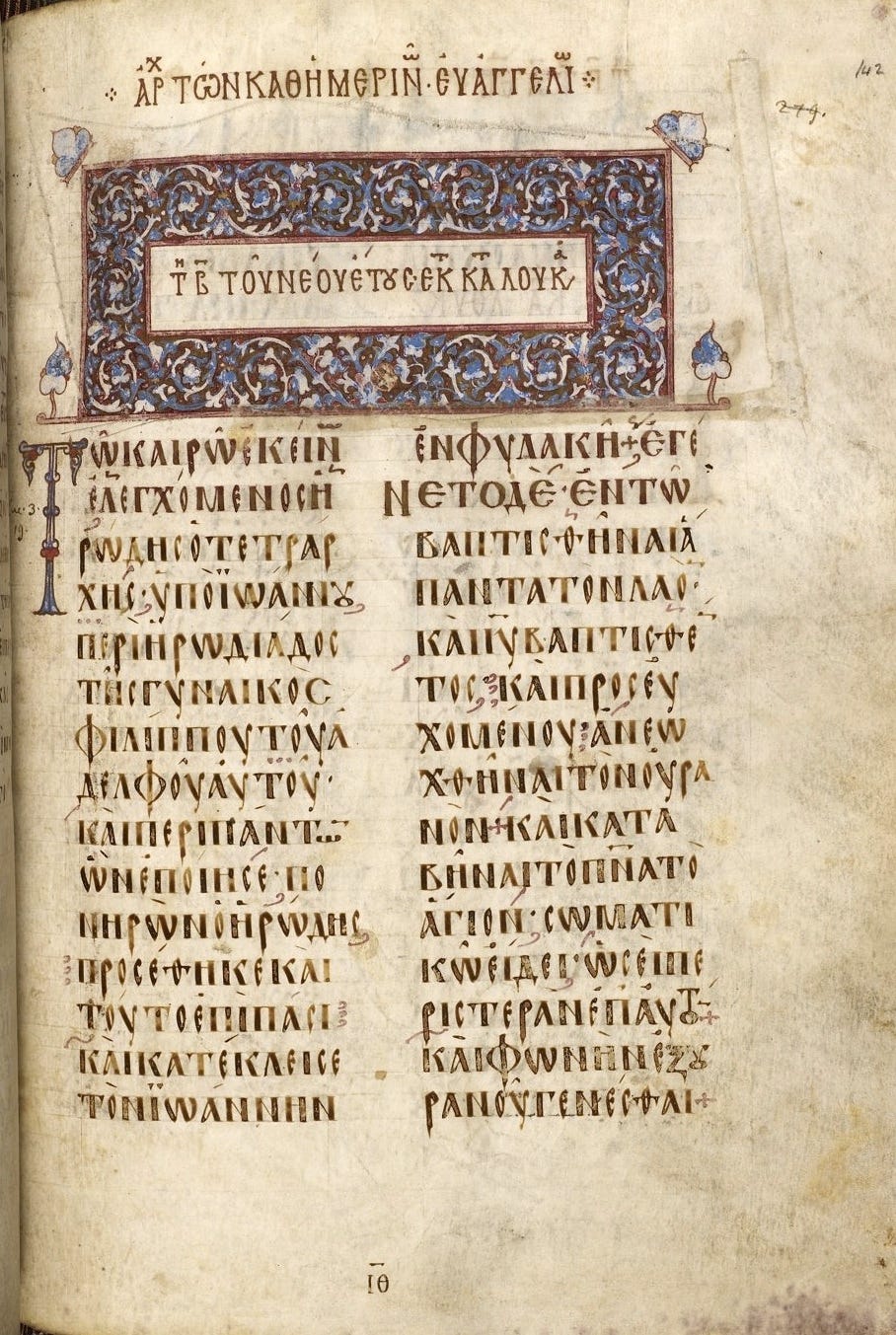

Some of the earliest dated minuscule codices (so-called codices vetustissimi) survive from the mid-9th to mid-10th centuries. One of the oldest completely dated New Testament manuscripts written in minuscule is Minuscule 461 (the Uspenski Gospels, dated 835 CE), illustrating how the transition was both early and rapidly adopted in Constantinople and surrounding regions.

The timeline runs roughly like this:

Hellenistic and early imperial eras: Majuscule (uppercase) alphabets on papyrus; formal Alexandrian book-hands.

Late Antiquity (4th–6th c.): Co‑existence of uncial book hands and cursive documentary hands.

9th century: The "minuscule revolution" - lowercase letters appear systematically

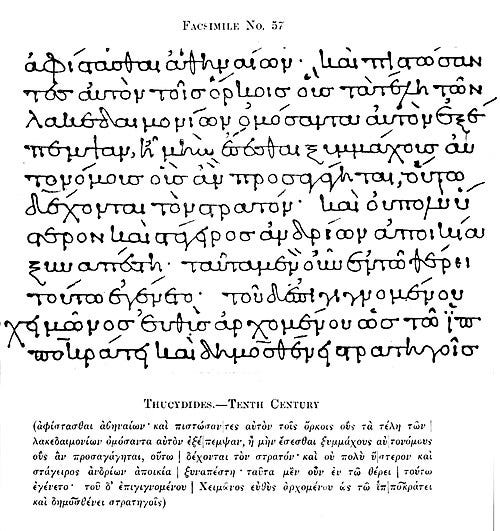

10th-15th centuries: Byzantine cursive develops from minuscule, becoming increasingly fluid

Post-1453: This cursive evolves directly into modern Greek handwriting

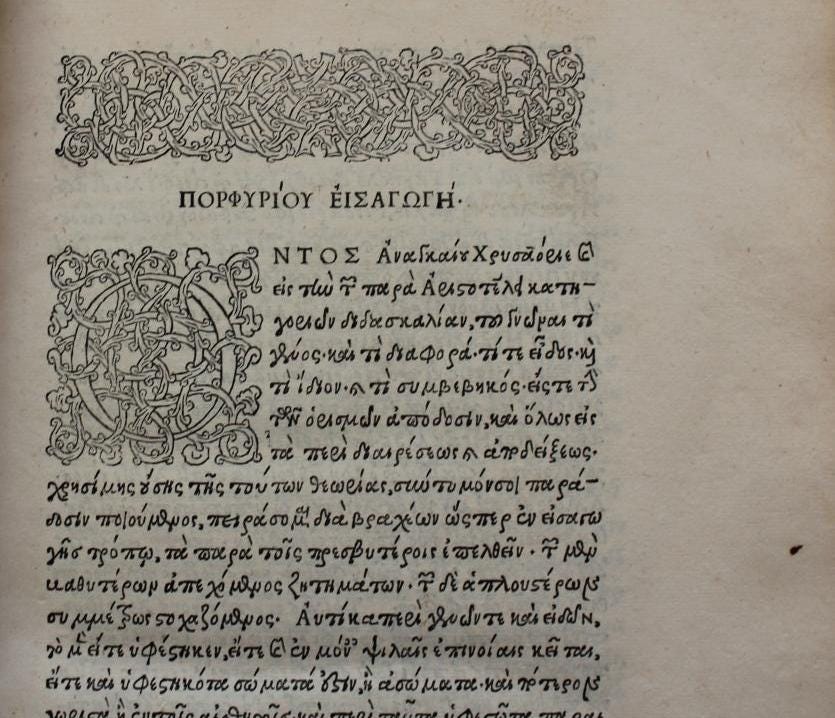

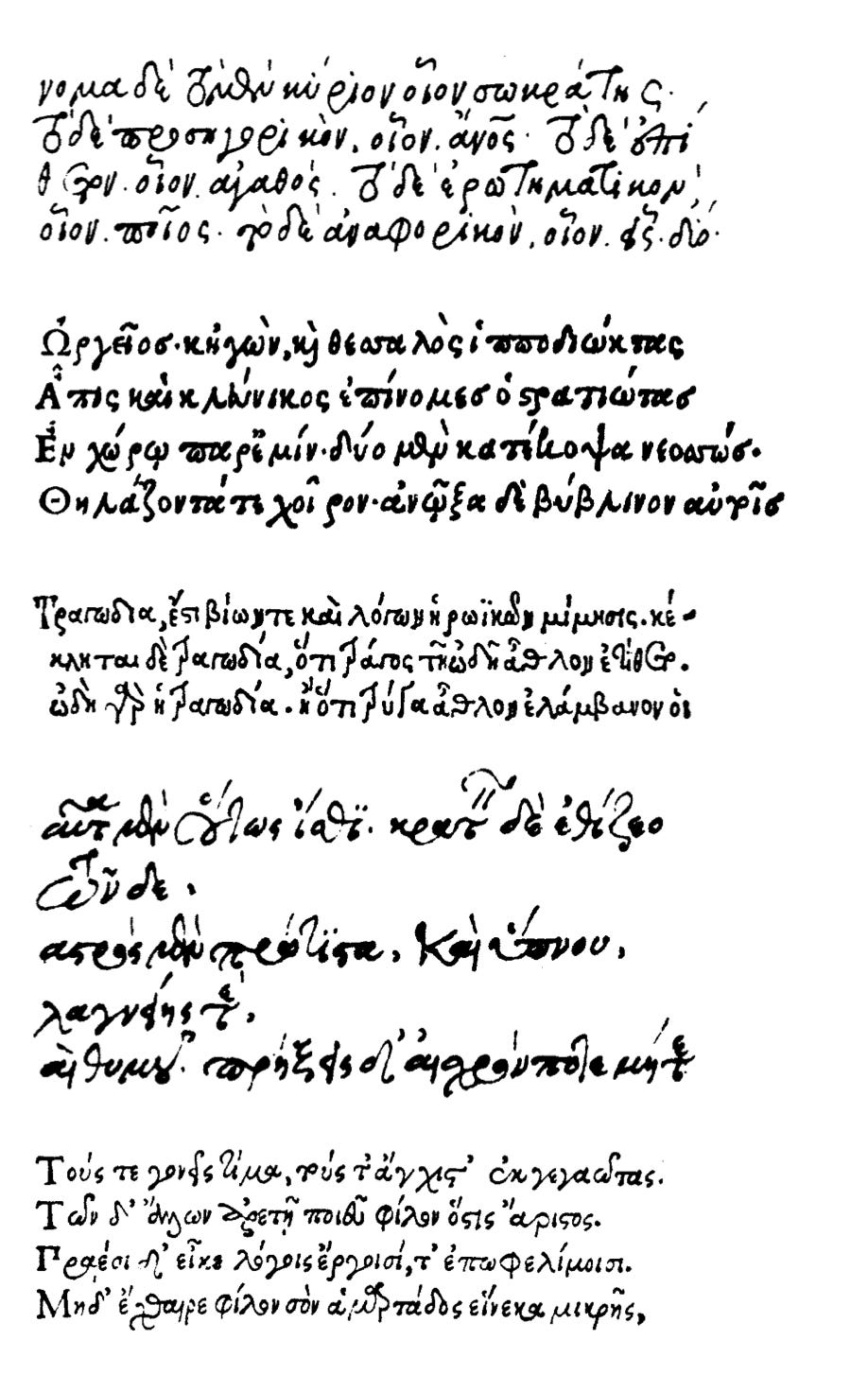

With the invention of printing in the late 15th century, another transition followed. Aldus Manutius in Venice, working with Francesco Griffo, established the first influential Greek typefaces, modelled closely on contemporary Byzantine handwriting.

These typefaces preserved the dense ligatures, abbreviations, and variable forms found in manuscripts. Later printers in Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Germany each developed their own conventions, sometimes increasing, sometimes reducing the use of ligatures and abbreviations.

As a result, printed Greek from different regions and periods can be difficult to decipher without specific expertise; modern OCR software typically fails to read them. Even specialists often consult readers trained in Greek cursive and older print to resolve letterforms or identify regional features.

I have often been asked to help decipher Greek passages in early modern alchemical texts printed in Germany, where the typefaces diverge considerably from those in Venetian or Parisian books. For those familiar with Greek typewriter fonts, however, much of this material remains accessible.

What makes Byzantine minuscule (and its printed descendants) seem impenetrable to the untrained eye is precisely what made it efficient: ligatures (connected letters), abbreviations, and the natural variations that come with rapid writing. It's the same reason modern cursive English can be hard to read if you've only learned print letters.

The Living Chain

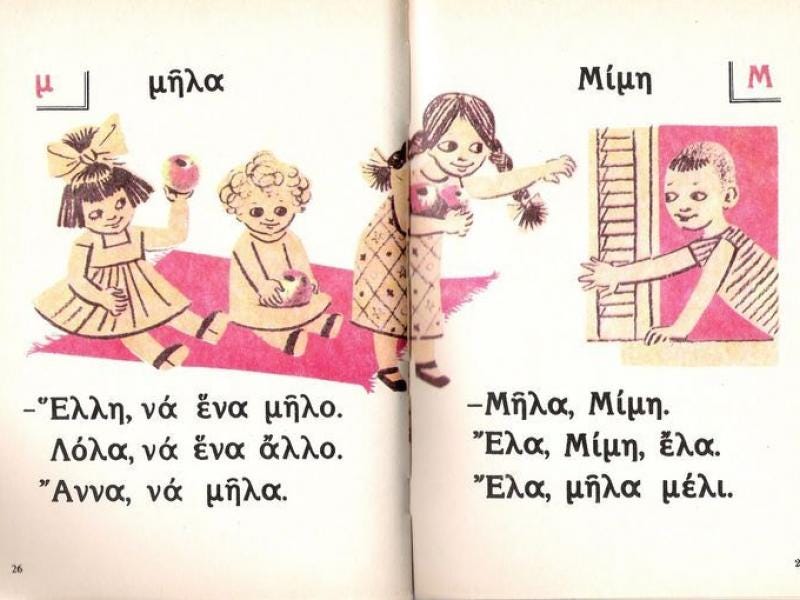

Here's what non-specialists often miss: this script never died. When I was five years old in a Greek elementary school, I learned to write lowercase Greek letters that are direct descendants of 9th-century Byzantine minuscule. By the sixth grade, age 11, we’d learned cursive.

My mother's recipes are written in a hand that would certainly be intelligible to a 12th-century scribe; calligraphy was still taught in her day (and until the 1970s). By my day, we had to practice our letters until we could keep them legible and in a straight line, but that was considered sufficient.

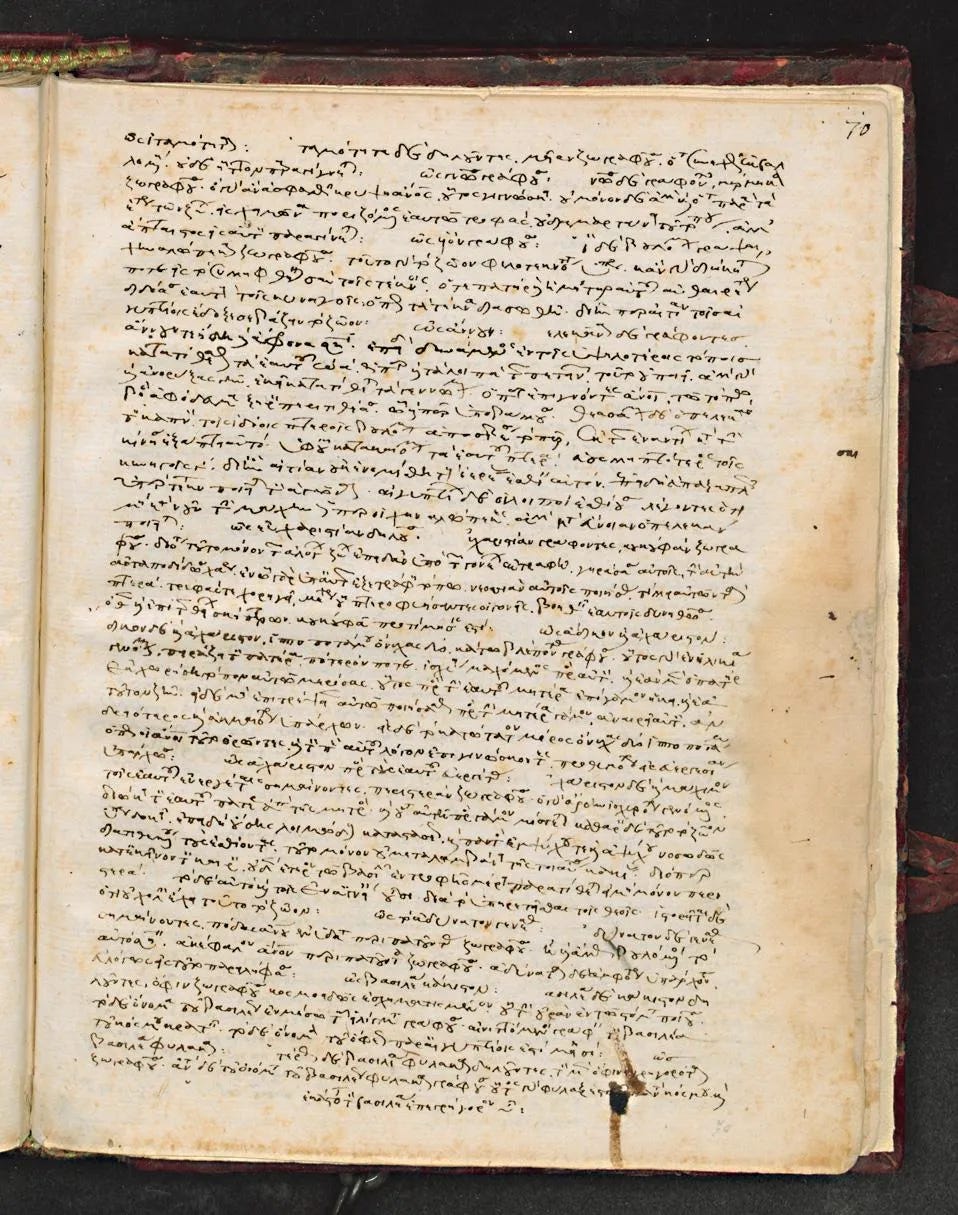

The "mysterious" Byzantine cursive that sends historians reaching for specialist paleographers? It's what we write our shopping lists in (see my script above; this is written without glasses and rushed). My mother’s 1950s typewriter - and my old schoolbooks - feature the same typeface.

Recently, while working on my critical translation of Horapollon's Hieroglyphica, I consulted several Byzantine manuscripts directly. Not because I have formal paleographical training, but because reading Byzantine minuscule is simply an extension of Greek literacy for those of us taught cursive. The real challenges weren't the letter forms but the abbreviations, some of the more creative ligatures, and the occasional worm hole.

I’ve spent 18 years tracing the afterlives of Greek script and symbol, both in the margins of medieval manuscripts and in the emblems of Renaissance art. If you’ve followed my work on Thyrathen or in my published studies on alchemical emblems and late antique symbols, you know that decoding these connections is more than an academic exercise: it’s a matter of accurate historiography and reclaiming neglected knowledge.

This continuity across manuscripts, typefaces, and ordinary handwriting has never really broken, for anyone raised reading and writing Greek. Yet in Western scholarship and the art it inspired, this living script often becomes something else: a symbol of lost wisdom, mysterious and foreign, needing expert mediation.

Especially in Renaissance circles, the visual symbolic expression of ‘a multiplicity of discourses’ was intended as a path to the “re”-discovery of a prisca sapientia; lost ancient wisdom and the sacred language in which God supposedly spoke to Adam. Ficino’s interpretation of Plotinos and of Egyptian hieroglyphics is largely responsible for this (but I digress - it’s in my books).

Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in Dürer's Allegory of Philosophy.

Dürer's Lesson

What strikes me about Dürer's Philosophy is that a German printmaker in 1502 showed more respect for Greek textual tradition than many modern Classicists and Byzantinists. He understood that Greek philosophy couldn't be fully represented without Greek script. He didn't transliterate into Latin letters or substitute decorative pseudo-text. He found someone who could read Greek manuscripts and faithfully reproduced what he saw. That is visible in the use of cursive π and κ (which I have also used above - again, learned young), as well as the natural, unforced ligatures.

This Renaissance moment of cultural transmission stands in sharp contrast to the modern academy's treatment of Byzantine texts. When historians today claim "we can't read it yet," they're performing a kind of intellectual colonialism - positioning basic Greek literacy as specialist knowledge while simultaneously claiming authority over Greek cultural production.

Gentle proposals to engage with the living language are brushed aside; more forceful ones labelled. I cannot provide examples of the kind of pushback I’ve received over the years without “naming and shaming,” and I will leave that for those who believe it effective. I am naming the phenomenon alone, in the hope that it will eventually spark constructive dialogue.

Why This Matters

The mystification of Byzantine script serves a particular narrative: that Byzantine civilisation is fundamentally discontinuous with both ancient Greece and the modern Greek world. It's a convenient fiction that allows Western scholarship to position itself as the necessary interpreter between Greeks and their own heritage. This in turn is based on historical dynamics that I explore throughout Thyrathen; this piece is a good starting point, this is another.

But here's the truth: there's no lost art to recover. Millions of Greeks read and write in a script directly descended from Byzantine minuscule. Including some abbreviations.

Beyond the script, Byzantine texts range from archaising to the vernacular. The majority are written in medieval Greek which is about as different from Modern Greek as Samuel Pepys’ diary is from Modern English. Hardly taxing. If you know Modern Greek, that is. It might be more of a stretch if you’ve confined yourself to Homer in some misplaced quest for “authenticity.”

The "code" that needs "cracking" is our daily handwriting. The paleographical expertise genuinely needed for Byzantine manuscripts isn't about basic letter recognition - it's about understanding abbreviations, dating hands, recognising regional variations, and navigating the material challenges of damaged texts.

When we pretend that Byzantine Greek is impossibly foreign, we're not protecting specialist knowledge. We're erasing a living tradition and replacing it with an orientalist fantasy of lost wisdom. Dürer, with his careful Greek letters surrounding Philosophia herself, understood something that seems to escape many non-Greek scholars refusing to engage with the modern Greek language: Greek text is Greek text, whether carved in marble, written on parchment, or scrawled in a modern notebook.

Next time you hear someone say "nobody can read these scripts," remember: millions do, every day. It's not a lost world.

But the story doesn’t end with handwriting. What the Renaissance made of Greek letters, and what was lost, misread, or relegated to the stacks, changed the way the world understood “philosophy,” magic, and wisdom itself. If you want to see how Dürer’s woodcut exposes the deeper mechanics of cultural appropriation, universalising, and Renaissance magic, that’s where the real decoding begins.

Want to see what Dürer’s Greek actually says? I break down the full inscription, letter by letter, with images—and reveal why this single woodcut rewrote the history of Western esotericism. Only for paid subscribers.