As promised in the feature article on Greek Iatrosofia, here follows a selection of iatrosofical instructions for healing both physical and magical afflictions, along with analysis of some of the references within them.

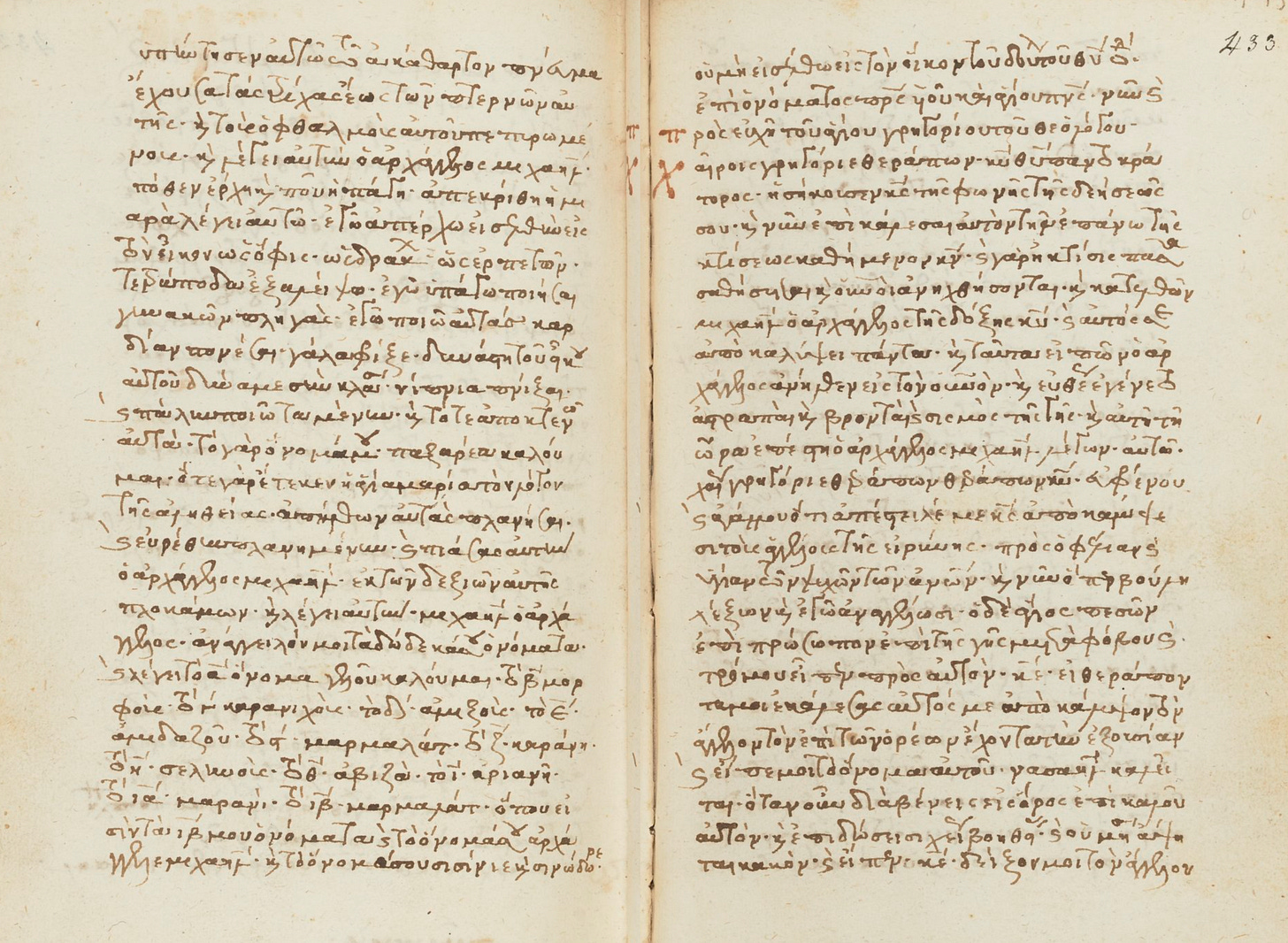

These are found in Paris Grec 2316, which includes an unpublished iatrosofic grimoire either copied or belonging to one Ioannis Stafidas, dated to 1364.

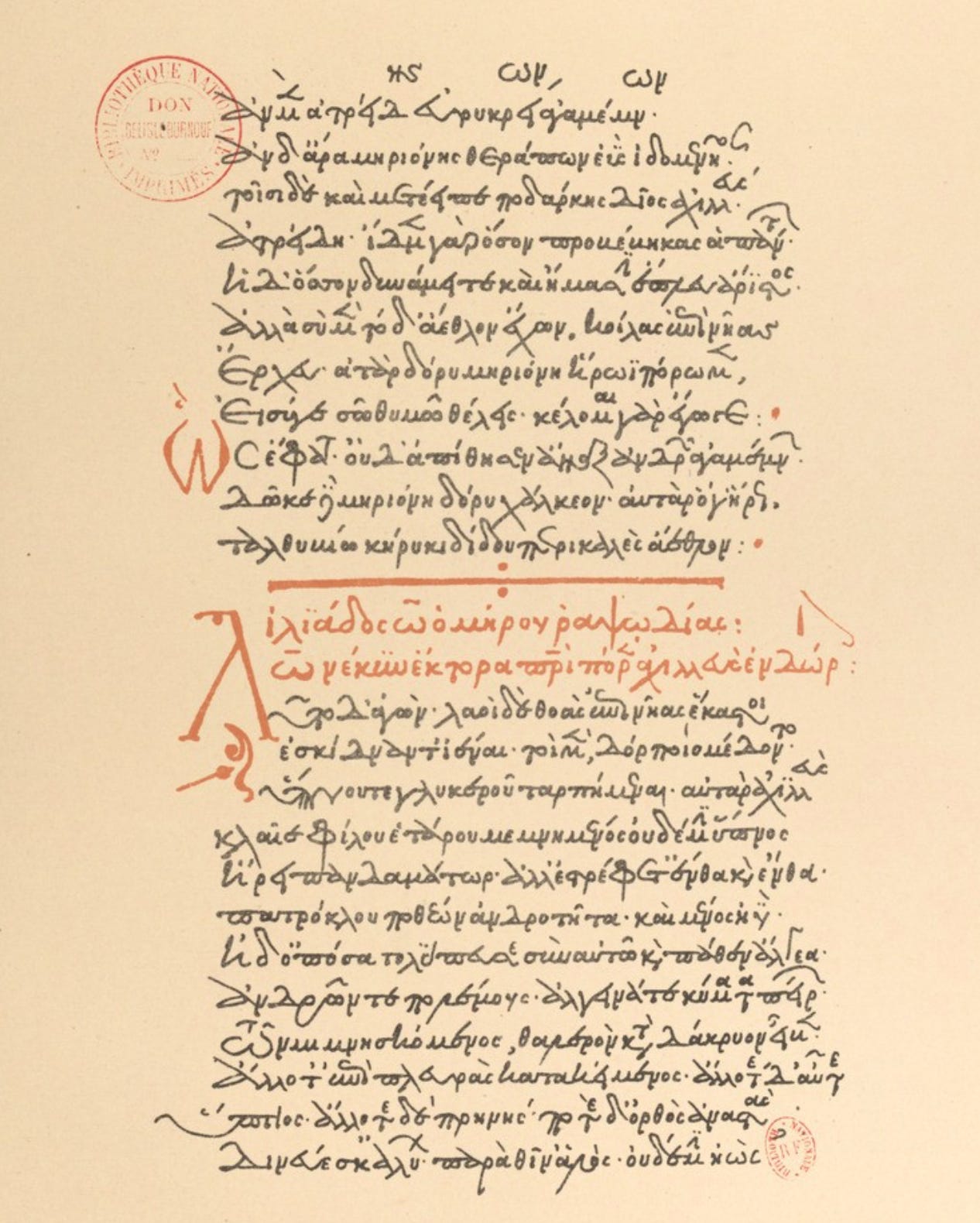

Only snippets have been published in various journals, upheld as curiosities by 19th century scholars. In gathering this material, I happened on a very helpful 19th century facsimile of the 15th-16th century Greek manuscripts in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France: it included some intriguing details.

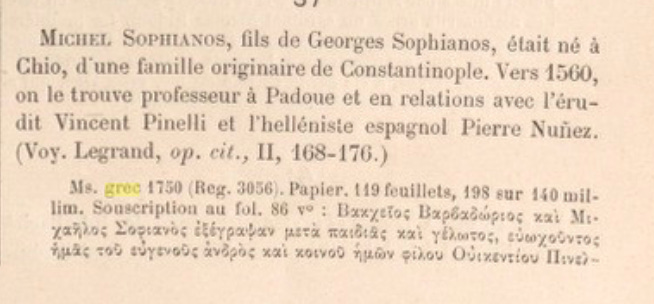

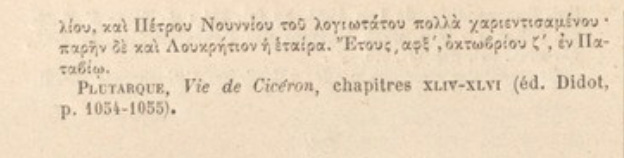

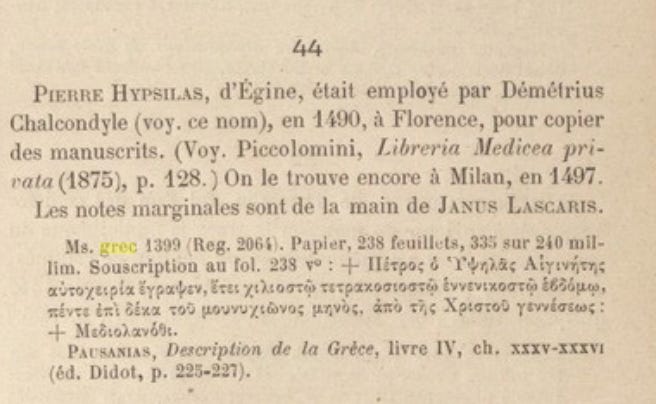

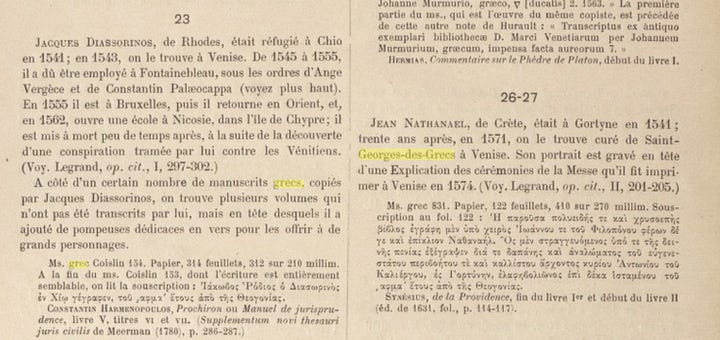

The Facsimile volume also held some curious surprises: biographical details of the Byzantine copyists whose handiwork the manuscripts are. All of them Greek exiles in free parts of Greece (Corfu and Crete) or Italian cities, they seem eager to leave a personal mark in ways that the anonymous monastery scribes rarely did, providing some rare insight in the process:

Each of these snippets contains the French translation of the Greek copyist’s identifying notes. One of the more interesting details is that some of them use the ancient Attic names for the months, within a Christian designation of the year:

"Petros Ypsilas of Aigina wrote this by his own hand, in the year 1497 from the birth of Christ, in the month Mounichion (April);" (lower right); while others use the terms: "on the tenth day of the Elafivolion (March) month, in the year 1541 since the Theogony (birth of God)." Poignantly, the one on the top left mentions the joy and laughter he and his fellow-copyist enjoyed while fulfilling their commissioned task. These were just some in a long line of Byzantine scholars, already some generations removed from the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, who applied their skills to the preservation of this material, which includes Homeric, Neoplatonic, and other philosophical material.

Buried among these texts is the curious - and very early - Stafidas Iatrosofion.

The Stafidas Iatrosofion

Considered a curiosity on account of its idiosyncratic use of vernacular Greek as well as its magicoreligious content and remedies for various ailments as well as concerns ranging from evil spells to seeking lost treasure, the Stafidas has never been fully translated.

Several excerpts have circulated in Greek and French special-interest periodicals since the late nineteenth century, but to my knowledge these are the first renditions in English.

They include spells to break curses, exorcise demons found only in Mediterranean and Byzantine demonology, and include clearly Solomonic elements as well as features familiar from the PGM. Here are their translations, along with an explanation of their referential framework.