Iatrosofía: Greek "Curanderismo"?

A living tradition of folk medicine and magic transmitted by women (and monks!)

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

Enjoy the free content but currently unable to subscribe?

In a recent interview with author, ceremonial practitioner, and content creator Ike Baker who makes Arcanvm podcast, we chatted about much of the background to my work here at Thyrathen and the lived experience of growing up Greek. Like me, Ike also has Greek roots, and he quickly recognised some of the practices I described, commenting on his Greek Yiayia (grandmother) and some of the folk practices she used against illness.

In the last few weeks I made similar connections with members of live audiences: a Cuban lady watching a talk on living avatars of pagan gods I gave for a private study circle (see preview here) noted the similarities between Santeria and modern Greek folk beliefs I was describing.

Following a talk for another private group (more here) a Mexican gentleman asked me to elaborate on the practices I write about, and we noted the similarities between the folk traditions in our respective backgrounds.

These encounters inspired today’s offerings and I must thank all involved for their input!

NB. This is a vast subject that cannot be done full justice in even a long-read feature article. I will circle back to topics only briefly touched upon here depending on interest ! Comment below with your feedback!

Greek Iatromanteis: A family matter

Four centuries before Asklepios and nine centuries before Ippokratis, the legendary Melampous (Μελάμπους, lit. meaning, Blackfoot, 14th century BCE), archaic king of Argos and grandson of the settler of Iolkos Kritheas, is the earliest known Iatromantis: a healer and diviner. The Melampodia (Μελαμποδία) was an equally legendary compendium of three books telling the story of Melampous and his healer-diviner descendants and successors, alongside records of medical and pharmacological knowledge and tales of his healing successes.

Only fragments of the Melampodia remain, but attestations from ancient writers including Theophrastos, Herodotus, Apollodoros, Pavsanias, Strabon, and Galen highlight the significance of the archaic iatromantis in ancient society, and reflect the belief system and methods that have reached us in various forms.

Melampous was thus named as his mother was said to have left him asleep under an olive tree, but his legs were in the sun and so he was dubbed “Blackfoot” after he tanned unevenly - a sign of being touched by Apollon. Snakes are said to have cleaned his ears as he slept, whispering healing secrets.

Centuries later, this story was adopted for Asklepios, alongside variants telling that he acquired his healing powers through drinking the blood of Medusa at Athena’s instruction. She later showed him how snake blood could heal or kill, reflecting the nature of farmakos and the significance of dosage; these narratives established the sacred role of the snake in relation to healing, but also formed the basis of modern toxicology long before Paracelsus.1

One of Melampous’ most widely known “cures” was the application of the cathartic properties of black hellebore to treat mania among Argeian women said to have been struck in punishment by Hera (other sources say Dionysos or Aphrodite). This attestation led to his being seen as “the first psychotherapist.”2

Modern science has tested some of Melampous’ methods and found them ineffective (hellebore has no effect on mental illness), but his (and later, Asklepios’) stories tell us much about the significance of iatromanteis in Greek culture: those with power over life and death, who could heal even curses from the gods, and for whom physical and spiritual complaints went hand in hand.

Both Melampous and Asklepios are said to have fathered dynasties of healers (the Melampodides and the Asklepiades). Asklepios’ daughters ( Aigle: rude health; Ygeia: prevention; Panakeia: the last hope of the terminally ill; Iaso: successful healing) are known to us, said to have been great healers in their own right.

While they may straddle the borderline between myth and legend, their names, and the fact that they are women, are important to our understanding of how the healing arts were, and are transmitted and perceived: the family connection through female lines is repeatedly seen in the healing arts.

Classical antiquity saw a sudden burgeoning of early “scientific” medicine through the influence of Ippokratis and a greater emphasis on methods of naturalistic observation and early medical ethics. While much of what we call the Hippocratic Corpus is pseudepigraphical, it still reflects the perception of health, disease, and the ethical perspectives of both classical and late antiquity, as well as the perceptions of the connections between body and soul.

In the correspondence with Demokritos attributed to Ippokratis, much is made of the latter, especially the phrase «Ιητρός γαρ φιλόσοφος Ισόθεος» (When a physician is a philosopher [virtuous] he is equal to God). This establishes the close connection between the healing arts and the broader definition of philosophy, which was not, as it is seen today, a solely intellectual or theoretical pursuit, but applied across the natural world and everyday life. Demokritean physics is inseparable from his contemporary philosophical concepts of metaphysics; so too, Hippocratic medicine is inseparable from questions of morality and mental well-being which make close reference to Platonic and Aristotelian pronouncements on the soul.

Thus, despite the evolution of empirical medical methods from the time of Ippokratis onwards, and the growing disdain for “superstition,” divinatory and other magicoreligious methods remained a large part of healing practice, particularly among the laity.

Greek Iatrosofía

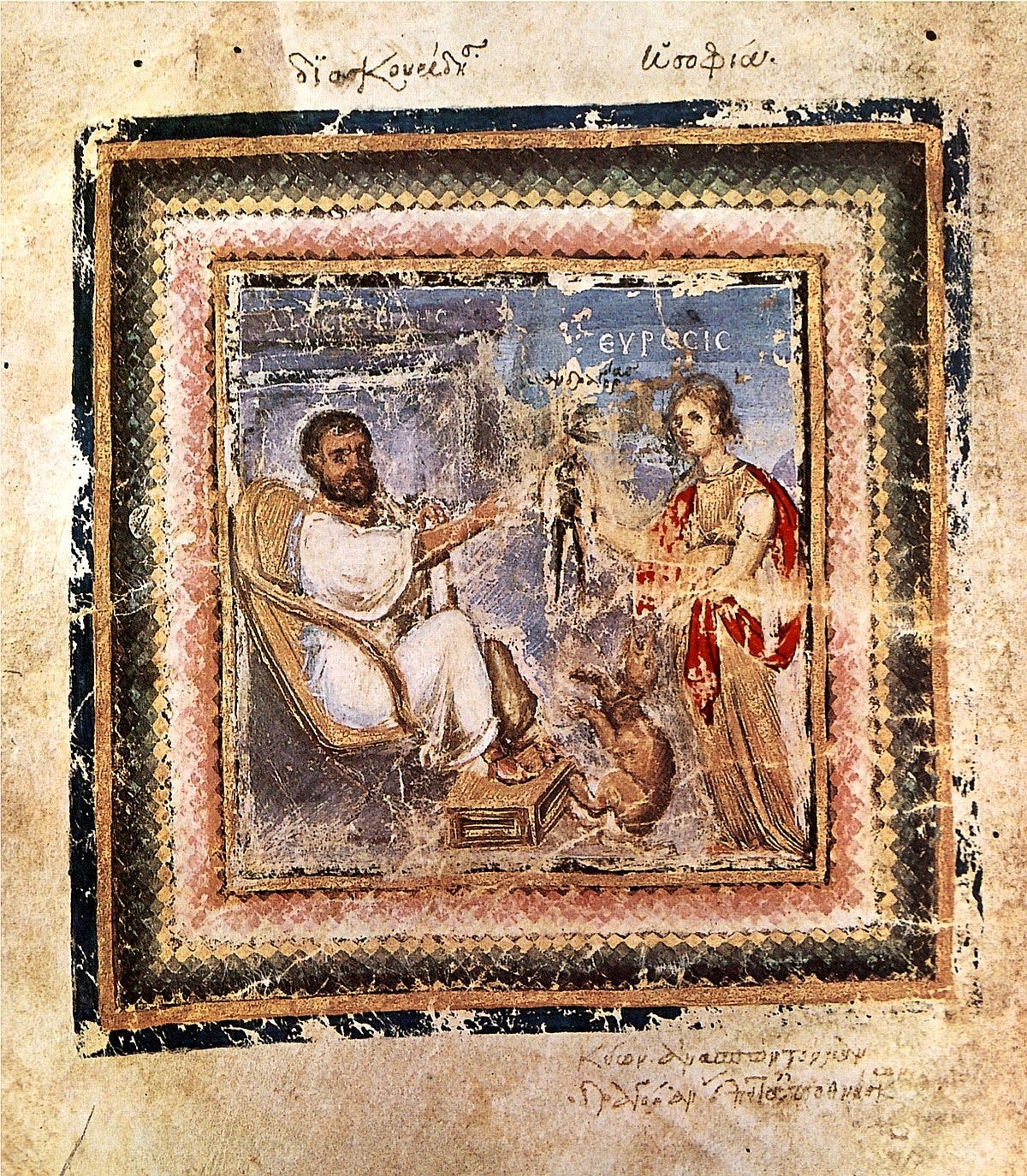

In late antiquity iatromanteia gave way to iatrosofía3 (literally: medical wisdom), described as a “genre of Greek medical literature” that originated in Constantinople. It comprises compendia of medical recipes and advice in vernacular Greek from various classical and post-classical periods.4

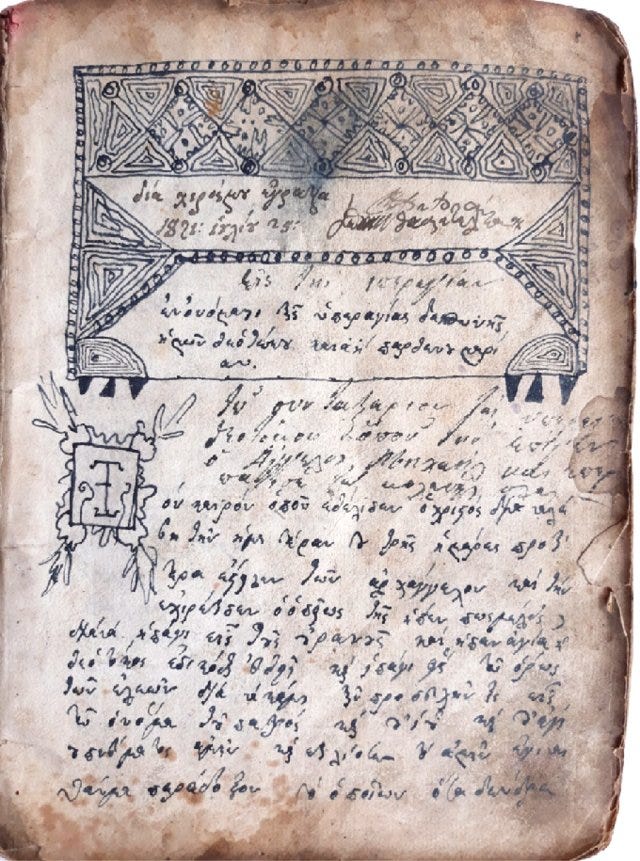

Though they have yet to be systematically studied,5 multiple iatrosofical manuscripts are found across libraries in Greece and overseas, dating from the early Byzantine period onwards, while a few deriving from either monasteries or private medical libraries remain in print and are distributed by modern publishers. Part medical manual and part compendium, I am working on the annotated translation of two of these.

They are invaluable sources on folklore, the evolution of science and medicine, as well as linguistics, and frankly the lack of interest in them is quite surprising, though possibly the result of scholarly ‘snobbery’ towards vernacular material, which is fortunately changing.

The most systematic scholarship of this material is found in Greek-language bibliography, as seen in the repository of doctoral theses (over a third of them containing a reference to folk medicine), but once again the language barrier precludes its better dissemination;6 a point that I have previously questioned.7

Some of the pharmacological recipes within these manuscripts have been proven to derive from Dioscorides among other early sources, with close textual research revealing that medical tradition within Greece has preserved multiple classical and late antique practices and beliefs.8

Alongside more recognisably protoscientific guidance, some of which contains pharmacology that has since been validated by modern research,9 numerous incantations and spells are also found. Some of them specify that they are to be used only by priests, but others are written for use by the patient, or by one skilled in such arts.

The introduction to such a compendium from a private medical library warns sternly against their use by those unprepared for the spiritual burden of healing the sick, and the second part of the compound “sofos” should give us pause. By the 19th century the Iatrosofistes came to be known as Iatrofilosofoi: Physician-philosophers, drawing on the Hippocratic use of both terms.

An Iatrosofical magic incantation

I apologise to readers for the painful topic of the sample I offer here; nevertheless it is an excellent example of the nature of the proffered cures that are listed side by side with bona fide herbal remedies, childbirth techniques, and surgical methods, some of which have since been found effective and safe by modern science:

On haemorrhoids

He who has haemorrhoids: The afflicted comes and lies facing east, and the priest steps on him with his right foot, [and] blesses him as follows: “Hail moon (x3), I greet you moon; I consecrate you to the one who has called you forth and generated you, and the resurrected Lord Jesus Christ and God, I consecrate you to the sickle of Zacharias; I consecrate you to the vestment of the most Holy Theotokos, to freeze the internal haemorrhoids, and the external bloody haemorrhoids, and the intestinal ones, and the discharge. I pray and Christ provides health. The land is clay, the seed is sand, the couple is a field; as sand would not grow fruit from the clay, so may no internal or external bloody and intestinal haemorrhoids or discharge emerge from the mouth of this servant of God; in the name of the Father and the Son and of the Holy Spirit, for [ever and for eternity, Amen].10

The reference to Zacharias derives from the Book of Zechariah 5:1-4; part of the Septuagint that speaks of a vision that Zechariah has of a giant, flying sickle and the destruction it wreaks in divine justice (no, not a scroll , see the footnote!)11

Here it also plays the part of a historiola: a short reference to a scriptural or mythical story used to indicate to the polluting spirit that they will meet the same fate as those in the story. In the chapter from Zechariah, the sickle is used to punish thieves and criminals; the affliction is told it will meet the same fate.

The analogy between the earth, sand, and field is typical of the sort of sympathetic magic found in such incantations among rural populations. The call to the moon probably derives from late antique practices as seen in the PGM and related material, and is not unusual since the Greek Orthodox Church continues to follow the lunar calendar for the ritual year, reflecting the degree to which many such concepts remain integrated in the culture as discussed elsewhere. Note the instruction for the priest to step on the patient: the gesture denotes both the imposition of power over disease, and disease perceived as a demon to be cast out: we see the same gesture both on magical amulets and in Orthodox icons.

Other incantations contain elements directly from the Solomonic Key, still others from the PGM (examples will be forthcoming in paid posts and a forthcoming book). Depending on the source and purpose, some are obviously more Jewish in nature, whereas others are wholly Hellenised. Later examples include Arabic and Turkish elements, and together they quite clearly reflect the impact of the history of the region. Many remain untranslated and are the topic of my work behind the scenes.

I have translated several further examples: these will be shared in a separate piece later this or next week, time allowing as I want to write a brief commentary as well. Note the translations will ONLY be available to paid subscribers.

Who were the Iatrosofistés?

Byzantine iatrosofists largely continued the Hippocratic tradition of philosophical as well as “scientific” learning and its application. Medical knowledge of the day rested on the Ἐπιτομῆς Ἰατρικῆς βιβλία ἑπτά (Compendium of Medicine in Seven Books) by 7th century travelling physician Paul of Aegina (Παῦλος Αἰγινήτης) who practiced in Alexandria.

Drawing on far older Egyptian and Greek sources, but also featuring novel (and in some cases highly effective surgical) techniques, this compendium became the mainstay of Byzantine medicine for 800 years and one of the main sources for both Arabic and Western medieval medicine as well.12

Though medical evolution of the Islamic Golden Age is well studied,13 what remains less understood is the parallel evolution within the Byzantine world, where further innnovations were made,14 expanding on the core provided by Ippokratis and Ghalinos (Galen) via Paul. The empire fostered a number of formalised hospitals, including the Basileias founded by Basil of Caesarea in the late 4th century.

These institutions integrated both medical and spiritual healing based on the principle of Christian charity and Hippocratic ethics. The University of Constantinople taught both male and female physicians, all of whom made use of Paul’s compendium and newer innovations to apply a form of holistic care that consisted of dietary modifications, hydrotherapy, herbalism, and prayer.15

Midwives, Farmakeftrai, Epaodoi and Manteis

In Byzantine material we find significant interplay between elite and vernacular material across genres - beyond established cases in literature and poetry, this was the case in medical literature too, where practical concerns informed this exchange.

Complex cases in institutional settings may have been the province of male doctors, but in domestic settings across the land and irrespective of social standing, midwives - known as μαιαί - were in charge of community healthcare, and this situation remained the same until the mid-twentieth century. They also took charge of women’s health, childbirth, and infant care across all social strata.16

This had been the case since late antiquity, when the professional designation ἰατρόμαιαι (iatromaiai: physician-midwifes) was already in use, and their equality to male physicians formalised in law.17 Some even wrote their own compendia: Aspasia in the 4th century CE is one of the few names to be preserved, along with that of Metrodora, but both demonstrate their theoretical knowledge and instructions for the reader.18

Unfortunately the reasons for women finding themselves in such powerful roles was not down to acknowledgment of their abilities; rather it was due to disdain and disgust for the female body expressed by Galen and held by many male physicians.19 Nevertheless, this catapulted women into a key role for the mediation of both healing and culture - and ensured a path of transmission for these practices.

The training of these physician-midwives was both formal and experiential, but all would have drawn on the same basic source of textual knowledge and made their own copies. With access to every home, it was through midwives that medical learning was fused with folk belief and ritual from folk healing and recorded in written texts. The use of magical practices and rituals in relation to healing was especially widespread, well attested, and despite official censure, persistent.20

Hence the epithets - sometimes, but not always, pejorative: farmakeftra can mean both a pharmacist and a poisoner reflecting the dual nature of farmakon. Epaodos is an incantor, one who speaks or sings incantations. And a mantes (the feminine form, η μάντις, pl. μάντεις) is of course a diviner: for all these methods belonged to the arsenal of the iatromaia.

From Iatrosophia to giatrosofia

Γιατροσόφια (yiatrosófia) is the vernacular word for Iatrosofía, now used pejoratively to refer to folk medicine in comparison to biomedical science. Greece has a fully modernised medical infrastructure available which is used by the majority of the population.

However, there are very few individuals who do not recourse to magicoreligious methods, or at the very least, prayers, as well, so much so that almost every Greek hospital houses a chapel, healing votives are found in their thousands in every church, requests for healing prayers are made regularly on Sundays, and many will apply folk methods alongside scientific ones.

Every Greek reader will be familiar with the scenes from this 1958 film whether they have seen it or not: Η Κυρά μας η Μαμμή: Our Lady Midwife (I could not find a clip with subtitles, sadly).

It centres around the arrival of a modern, scientifically trained doctor in a small village of the Peloponnese, where the only medical care is provided by the local midwife. When all else fails, she recourses to herbs, magical techniques, and above all, a charm against the Evil Eye hangs around the neck of every villager.

In one scene she performs a spell to rid an ailing child of the evil eye after mocking the doctor for the aspirin he offers. The spell and accompanying ritual clearly features elements recognisable from late antique Greek incantations. The film’s comedy value rests in the conflict between the midwife and the doctor, each representing an entirely different form of medicine. As luck would have it, in the end their children fall in love and marry, but the bickering continues until the end.

The dismissal of the midwife’s ways as so much mumbo-jumbo by the good doctor summarises the modern meaning of yiatrosófia, the once venerated Iatrosofía.

Nevertheless, the film provides a valuable record of the ubiquity and survival - no bones about it - of the Greek folk healing tradition. The film was made precisely at the time that modern “Western” biomedicine began to spread in Greece and reflects the very real culture clash at play.

Though this point deserves an article of its own, suffice it to say that much like other cultures with a strong indigenous element and pre-modern conception of time, in modern Greece, traditional medicine, complete with incantations, talismans, and rituals, persists regardless of the now widespread adoption of modern science.

Iatrosofía vs. Curanderismo

The easiest analogy for the degree of integration between modern and traditional medicine in Greek culture is that of Curanderismo, the folk healing tradition found in a number of regions of South America. The similarities are many, the differences important.

Unlike Greek traditional medicine (which appears to stop for scholars after Galen), Curanderismo has been studied closely in relation to patient perception and how the two approaches to healing can work together given the strong hold of the belief system among many patients. In contrast, in Greece its pejorative dismissal continues among those who fear the loss of our tenuous “European” status, a complex issue that requires its own dedicated treatment.21

One useful study of Curanderismo describes it as follows:

Curanderismo is a diverse folk healing system of Latin America. Eight major philosophical premises underlie a coherent curing world view of Latino patients: disease or illness may follow (1) strong emotional states (such as rage, fear, envy or mourning of painful loss) or (2) being out of balance or harmony with one's environment; (3) a patient is often the innocent victim of malevolent forces; (4) the soul may become separated from the body (loss of soul); (5) cure requires the participation of the entire family; (6) the natural world is not always distinguishable from the supernatural; (7) sickness often serves the social function, through increased attention and rallying of the family around a patient, of reestablishing a sense of belonging (resocialization) and (8) Latinos respond better to an open interaction with their healer. These nuclear ideas or attitudes about health, illness and care are culturally patterned and are both conscious and unconscious (implicit). Moreover, expectations of the nature of the patient-healer relationship have implications for medical practice in general and psychotherapy in particular.22

The briefest of comparisons with the Greek tradition reveals the following:

Association of disease with strong emotional states: This is well known in Greek tradition, and the negative emotions named above are personified as folk demons and she-demons. Envy especially is one of the most feared she-demons (known as Gyllou, Gyllo, Avyzou, Striggla, Lamia and other names), attested in the PGM, on late antique amulets throughout Byzantine times, recorded by Michael Psellos, in wondertales (including several on this site), and still reflected in traditions and superstitions surrounding childbirth. One of the translations I will share in the next article deals with her specifically.

Lack of balance and harmony; (3) innocent victim of malevolent forces; (4) Loss of soul: All three of these are found in the Greek tradition, but they are not the province of midwives; they are the domain of the priesthood.

Elaboration must wait for a future offering, but as I have noted elsewhere, in the Greek Orthodox tradition, sin is not perceived as it is in Roman Catholicism or other Christian denominations; it is seen as a sickness of the soul, and as such, it is a priest who must deal with it.

The vast majority of observant Greeks have a “spiritual father,” who may be their parish priest, or may be a monk (they are often stationed in “metochia” - monastery subdivisions located in cities where they do such work). Such “soul-sickness” is often the topic of long conversations with one’s spiritual father, which is distinct from both confession and prayer, though both may occur; however it is far closer to a counselling session (and very similar to certain curandero practices). This Greek phenomenon is one of the reasons for which professional psychotherapy remains low in uptake among older generations (Gen X and older); a valuable sociological study of this is available here.23Participation of the whole family; (7) Social participation: In the Greek setting this is not a formal characteristic, but traditionally, someone in the family usually knows, or is called on, to perform domestic healing rituals if a priest is unavailable, and this is overwhelmingly women’s work. Beyond this, a priest may advise family participation if the nature of the problem calls for it. Greek families overwhelmingly look after their elderly and infirm; nursing homes are few, poorly maintained, and only for those without living relatives.

The natural world is not always distinguishable from the supernatural: This is extremely true of Greece, even in urban settings, and one of the core elements to grasp if wishing to understand Greek culture. 24

Seven of the eight principles appear in some form, as seen in this briefest of comparisons. While a full transcultural study is needed, a quick look at practices reveals more shared traits between the two traditions.

Unlike curanderismo, Greek folk medicine lacks formal apprenticeship or initiation. Viewed as outdated or superstitious, some (but not all) of these practices face official disapproval from the church, yet persist quietly. They are passed down, usually from older women to younger kin. If no daughters exist, sons are taught instead. Some methods require secrecy: some only share this knowledge near death, binding successors to silence.

Most of my acquaintances know at least one evil eye banishment spell; a few hold deeper knowledge but guard it until the right moment. My partner, taught by his childless aunt, will not share his knowledge despite my urging, but I’ve seen his skill in action.

Greek villages lack a “curandero” figure; historically, the iatromaia filled this role. Now, parish priests and women taught by ancestors share it. While some knowledge has faded, every community knows a “wise woman” for ailments like soul sickness or the evil eye - and every mother knows to put an egg under the bed or raw onions on the feet to draw out fever!

Monastery Medicine

In parallel with the largely female line of transmission, a large body of iatrosofic knowledge has been passed down and used within monasteries for centuries; this is one of the key sources for its preservation and publication if family lines of transmission are broken.

The sources are similar: Byzantine iatrosofic texts alongside incantations that feature Christianised Solomonic elements. The practices include herbalism and a wide range of natural cures, many of which are easily available directly from monasteries.

Many monasteries on Mt Athos even feature an online shop with organically made teas, tinctures, balsams and even herbal supplements (vetted by a government agency for safety and efficacy) made according to traditional recipes. They also feature incenses made to recipes one can also find in the iatrosofic compendia, many of which are intended as adjunctive treatments for various mental and physical ailments.

Agapios of Crete

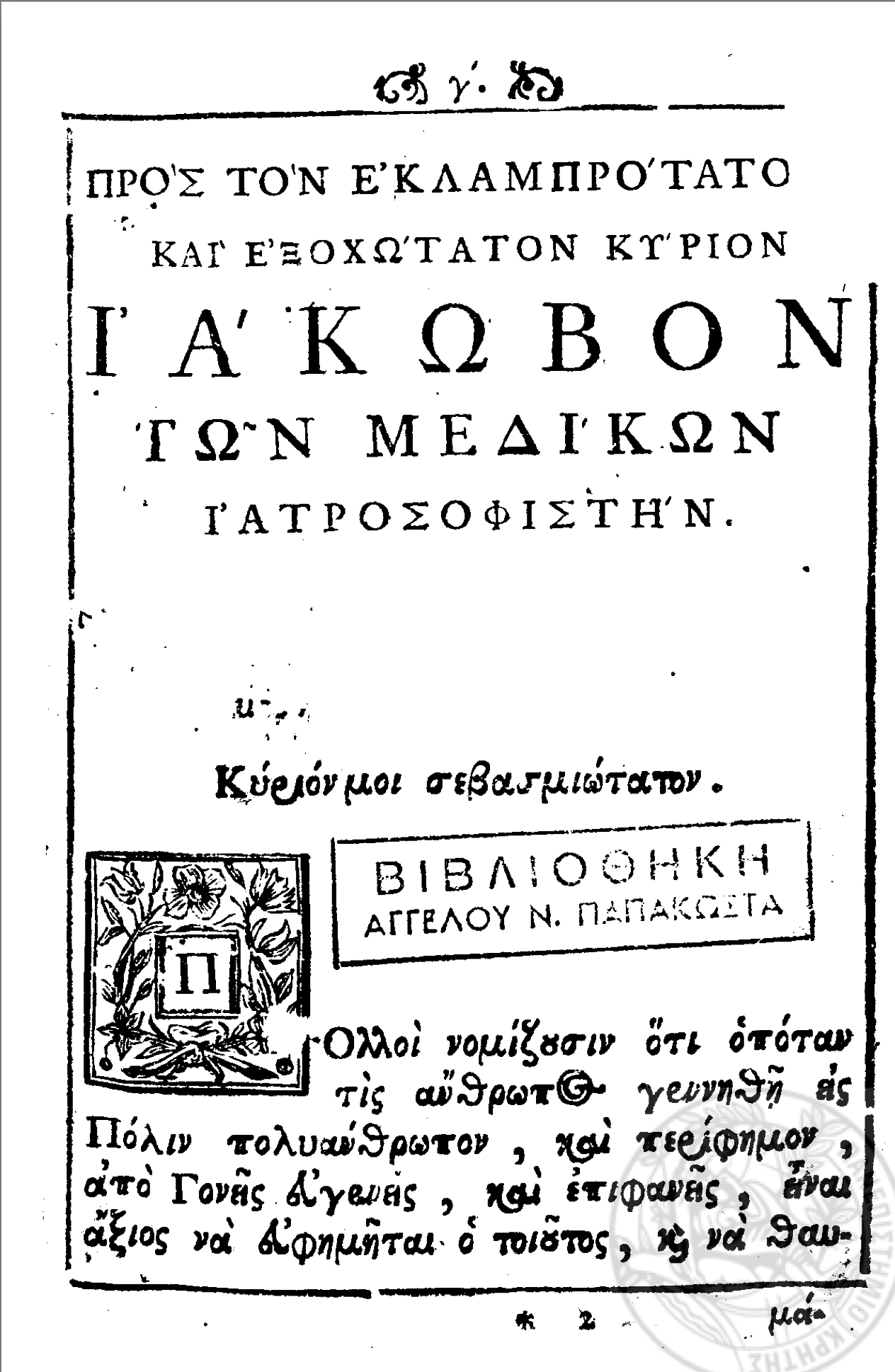

If one types ιατροσοφία into a search engine, multiple books appear, many of which are publications of such compendia attributed either to physicians of the past, or to monks. One of the best known belonged to Agapios (Landos) of Crete, a 17th century monk who died in around 1656. He spoke Italian and Arabic, and after becoming a monk on Athos, he spent his life studying, translating, and as a wandering healer.

His many books - some epitomes and some translations - were of medicoreligious content and for two centuries were among the very few printed books available to Greeks still under Ottoman occupation.25 His Geoponicon (above) includes entries such as “Uses of garlic; How to make chickens lay daily; Remedies for gas; How to find a drowned man; How to carve letters on metal,” and so forth.

This, alongside a number of similar books available from repositories and also in print may be among the key sources of preservation of such material among the lay population.

What’s in a name?

The increasing use of familiar terms to describe unfamiliar concepts raises concerns about cultural clarity. In Greg Shaw’s Hellenic Tantra, he uses the term to frame Neoplatonism’s non-dualistic elements for Western readers, clarifying it’s not a historical link. Similarly, Angela Puca’s study of Italian Segnature magic employs “shamanism” to reflect transcultural practices, acknowledging the term’s controversy but defending its broader application.

Both scholars note potential issues with such terms, with Puca offering consistent qualification. However, using labels like “shamanism” or “tantra” without nuance risks unintended consequences. First, it fosters assumptions of historical connections among traditions, leading to online misconceptions. This can obscure cultural distinctions, flattening unique ecotypes—variants of practices shaped by local history and identity, like Darwin’s tortoises, distinct yet related.

Though these precedents give me ample justification for today’s title, I chose it precisely because I wish to address these issues.26

Greek culture has been intensely misrepresented for centuries in both scholarship and popular culture, as I have discussed in depth here. This has had severe and often damaging impact on sociocultural cohesion as discussed by Jonathan Hall and other Hellenic Studies scholars.27 Excellent work has been done regarding such issues among other cultures; it is time this degree of respect in relation to Greek culture was applied by those who have benefited from it.

Careful terminology, like “Greek iatrosofía” or “Italian animistic magic,” better respects these differences. Second, misapplied terms may contribute to cultural appropriation, particularly when commercialized. Curanderismo, itself born of colonial oppression, now celebrated and reclaimed by its people, and Greek iatrosofía, long misrepresented, deserve precise naming to honour their contexts despite their similarities. Scholars should use accurate descriptors to preserve cultural integrity without borrowing loaded terms.

How to learn iatrosofía and its magic

Understanding Iatrosofía demands familiarity with its cultural context, language, and religiocultural dimensions, particularly folk Orthodoxy, which shapes its framework. This immersion reveals the tradition’s depth and nuance.

I am not urging others to pursue such a course, but I expect them to respect this and I do struggle with how to share these living traditions responsibly. As a scholar, I wrestle with presenting this material accurately, wary of seeing it oversimplified in trends like “Learn Greek Iatrosofía” courses, akin to misuses of terms like “theurgy” when it refers to a modern reinterpretation. Such missteps risk distorting a culture’s heritage.

For every scholar or practitioner who represents Iatrosofía thoughtfully, others inadvertently - or carelessly - perpetuate misconceptions, making it challenging for those tied to this culture to speak without misunderstanding.

This is why precision in language matters—terms like “Greek curanderismo” carry unintended connotations, and I used it myself to highlight just this. Curanderismo, while sharing similarities with Iatrosofía, remains distinct, rooted in a different cultural matrix. Iatrosofía stands on its own, a term worth learning. Neighbouring countries have similar practices from the same sources, and they probably have different names for them. Those too, are important.

I encourage scholars to use descriptors mindfully. Labels may mislead when applied to historical contexts, carrying modern baggage. Similarly, practitioners drawing on living traditions should clarify their work. Creating new practices inspired by Iatrosofía (or any tradition with a home culture) is valid, but without deep cultural engagement—language, place, context—it’s not Iatrosofía itself. It’s a modern interpretation, which is still valuable, but something new.

Samples from some of these manuscripts in translation will be posted over the next few weeks for paid subscribers only.

Enjoy the free content but currently unable to subscribe?

Elsewhere the same story of a snake licking his ears clean is also used for Asklepios. The snake in association with healing is a common trope in Greek myth, with various explanations given: this will be tackled in a future offering. For more see: Tsoucalas G & Androutsos G ‘Asclepius and the Snake as Toxicological Symbols in Ancient Greece and Rome,’ Toxicology in Antiquity 2e, P Wexler ed. (Elsevier, 2019), 257-265.

Aglaia Mpimpi-Papaspyropoulou, “Melampous: The Great Healer of Argos,” Peloponnisiaka: Minutes of the 2nd Local Conference of Argolic Studies (Argos 1986); Athens 1989; Argolikos Archival Library of History and Culture.

My choice of spelling is deliberate; there is no reason to use ‘ph’ when transliterating φ. The same applies to all Greek names and words unless they have become adjectives through common usage (eg. Hippocratic Corpus). Therefore, my use of iatrosofía, iatrosofic, iatrosofistés are not misspellings, but intentional decisions based on modern Greek transliteration conventions.

Lardos, A; Prieto-Garcia, J; Heinrich, M; (2011) Resins and Gums in Historical Iatrosophia Texts from Cyprus - A Botanical and Medico-pharmacological Approach. Front Pharmacol , 2 , Article 32. 10.3389/fphar.2011.00032.

Multiple iatrosophical manuscripts scattered across Greek and overseas libraries have yet to be catalogued; around 150 post-Byzantine manuscripts are thought to exist, while several partial catalogues dating from before the Renaissance are also available. See Lendari T, Manolessou I. The language of iatrosophia: A case-study of two manuscripts of the Library at Wellcome Collection (MS.4103 and MS.MSL.14) In: Bouras-Vallianatos P, editor. Exploring Greek Manuscripts in the Library at Wellcome Collection in London [Internet]. New York : Routledge; 2020 May. Chapter 4.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558646/doi: 10.4324/9780429470035-4

This search query using the terms “folk medicine” in Greek produced a list of 18,736 doctoral studies, many of which were produced in medical history departments of Greek medical schools: https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/simple-search?query=λαϊκή+ιατρική&submit_search.x=0&submit_search.y=0. Such results are one of the reasons I am strongly opposed to the insistence on terms such as “esoteric” or “occult” in relation to Greek material: it is not widely used nor do the scholarly definitions used in English-language scholarship apply.

Aside from the limited resources available to Greek universities, the question of Modern Greek being systematically neglected as a language of scholarly exchange remains a pointed one. See my discussion of this here.

https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/21490 ; https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/50092

Lardos, A; Prieto-Garcia, J; Heinrich, M; (2011) Resins and Gums in Historical Iatrosophia Texts from Cyprus - A Botanical and Medico-pharmacological Approach. Front Pharmacol , 2 , Article 32. 10.3389/fphar.2011.00032.

Ms 2316, f. 361 b; 362 a, in Émile Legrand (ed.), Bibliothèque grecque vulgaire, v. 2, Maisonneuve et Cie, Παρίσι 1881, p. ix-xxiv. Translation mine.

Multiple modern translations offer this as a “flying scroll” or “roll,” and not a scythe: this is down to a discrepancy in the Hebrew Masoretic and Greek Septuagint texts of Zechariah 5. The Greek word used is δρέπανον (sickle) and is unambiguous. Though popular websites use the “scroll” or “roll” translation, more specialised scholarship suggests that the version in Greek Septuagint is in fact the intended meaning, since the object of the vision was then used as an instrument of punishment. Source. Also see this version. All Greek versions I consulted are consistent on the use of δρέπανον (scythe or sickle). This particular reference to Zechariah is seen in a number of similar healing incantations in more or less detail, in some cases reference is actually made to the sickle cutting out disease.

Gurunluoglu R, Gurunluoglu A. Paul of Aegina: landmark in surgical progress. World J Surg. 2003 Jan;27(1):18-25. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6464-8.

Abdulrazeq HF, Ali R, Najib H, Doberstein C, Oyelese A, Gokaslan Z, Malik AN, Asaad WF, Greenblatt S. Al-Zahrawi (936-1013 AD): On the Surgical Treatment of Neurological Disorders by the Father of Operative Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2024 Apr;184:236-240.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2024.01.169. Epub 2024 Feb 6. PMID: 38331026.

Bouras-Vallianatos, Petros. Innovation in Byzantine Medicine: The Writings of John Zacharias Aktouarios (c.1275–c.1330). Oxford, Oxford UP, 2020.

Touwaide, Alain, editor. A Companion to Byzantine Science. Leiden, Brill, 2019.; Horden, Peregrine. Hospitals and Healing from Antiquity to the Later Middle Ages. Aldershot, Ashgate, 2008; Nutton, Vivian. Ancient Medicine. London, Routledge, 2004.

Bennett, Judith M. Women in the Medieval World. New York, Routledge, 2013; Congourdeau, Marie-Hélène. Childbirth in Byzantium: Christian and Pagan Practices. Paris, Éditions de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 2007.

P. Diepgen, Zur Frauenheilkunde im byzantischen Kulturkreis des Mittelalters, Abhandlungen der Geistesund Sozialwissenshaftlichen Klasse, 1-8, Mainz 1950, pp. 1-14; p. 11; Codex Ioustinianus, ed. P. Krüger, Corpus Juris Civilis, vol. 2, Berlin 1959 (9th edn.), 6.43.3.1 and 7.7.1.5.

Leo the Philosopher, Synopsis of Medicine, ch. 26; A. Vakaloudi, Contraception and Abortion from Antiquity to Byzantium, 128.

A. Vakaloudi, The contribution and occupation of midwives from antiquity to Byzantium, 22-3.

ibid., cf. A. Vakaloudi, Contraception and Abortion from Antiquity to Byzantium.

https://www.academia.edu/5968780/Cultural_Mismatches_Greek_Concepts_of_Time_Personal_Identity_and_Authority_in_the_Context_of_Europe_in_Kevin_Featherstone_ed_Europe_in_Modern_Greek_History_Hurst_and_Co

Maduro R. Curanderismo and Latino views of disease and curing. West J Med. 1983 Dec;139(6):868-74. PMID: 6364577; PMCID: PMC1011018.

Charles Stewart ed., Colonising the Greek Mind? The Reception of Western Psychotherapeutics in Greece, The American College of Greece, 2014.

‘Cultural Mismatches: Greek Concepts of Time, Personal Identity and Authority in the Context of Europe', in Kevin Featherstone (ed) Europe in Modern Greek History Hurst & Co (2012); Charles Stewart, Dreaming and Historical Consciousness in Island Greece, University of Chicago Press, 2012; 2017.

Σάθας, Κωνσταντίνος Ν. (1868). Νεοελληνική Φιλολογία. Αθήνα: Κορομηλάς. σελ. 313.

I am not intending to criticise fellow scholars by using these examples, I am highlighting a very common phenomenon which I understand and which I myself must take care with. I am choosing to do so in this context because it was so easy to come up with this title - and so I felt it was time to address it head on. I apologise if this causes discomfort; it is meant to spark constructive discussion.

https://history.uchicago.edu/directory/Jonathan-M-Hall