The Problem with Classics

On critical theory, dismantling Classics, and the invalidation of Greek voices

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

I must ask regular readers to forgive yet another delay in posting as I juggle three book projects at different stages. I am also setting up new courses (news soon!) and making arrangements for several conference presentations this year (news on recent and upcoming talks here). All this year’s projects (bar one medical book that I’m editing) are focused on the same topics addressed here at Thyrathen, and I really hope to see some of you at one or other conference!

This week features an excerpt from the commentary of my new (2025) book, Horapollon’s Hieroglyphica, a thoroughly new translation from the original Greek, with extensive commentary and notes. This is a snippet from a much broader argument - the rest is in the book.

I know that some readers looking for more pithy posts on Greek folk magic may be put off by this expansion of topic area. I won’t be going off on this track too often and have scheduled a couple of amazing topics replete with magic! But if you read this site because you’re interested in all things Greek, then I think you will find food for thought in what follows.

The Problem with Classics

Arguments for dismantling Classics and its historiographies cite its Eurocentrism, “Western” bias, and resulting “injustices and epistemologies of power.” Following the general thrust of postcolonial criticism, a method dubbed “Critical Ancient World Studies (CAWS)” aims to “dismantle the structures of knowledge” within a field that its proponents argue “has special relevance to the privileged and the powerful.” They also question “the categories, ideas, themes, narratives, and epistemological structures that have been deemed objective and essential within the inherited discipline of classics.”1

However, the arguments levied in support of this approach rest on a straw man vision of Greek, Grecian, and Classical thought and archetypes apparently fuelling hegemonic and colonial idealism. It is not that this vision does not exist in the broader “epistemological monoculture of Euro-American academic discourse:”2 it does and the argument is valid.

The real problem is firstly that this vision is the product of academic idealisation,3 not the myriad complex that is historical Greece and Hellenism, nor their complicated children, Modern Greece and Modern Hellenism.4 Secondly, appearing to conform to this vision became the price of supervised statehood and agency in the foundation of the Modern Greek state, in a form of persistent crypto-colonialism.5

This resulted in all things post-Classical, Byzantine, and especially Modern Greek being blamed for the subsequent colonialist attitudes towards non-Western perspectives on the basis of grand narratives alongside the essentialist and reductionist “barbarian/Hellenic” dipole - itself an inaccurate product of academic distortions.6

In short, Modern Greece attracted the blame and disdain for the Western academic reification and idealisation of “the glory that was Greece,” which also shaped Orientalist, exoticist and similar attitudes that were also applied to “Byzantium.”7 It then became “Othered" by those pushing back against the Western academic perspectives. Those seeking to compensate for such attitudes took the latter position, once again invalidating Greek voices or notions of agency.8

By way of example, a proposal for “decolonising” academic disciplines through embracing “simultaneous histories” presents such straw man visions of Modern Greece as being responsible for promulgating “Eurocentric imperial ideologies that [idolise] classical Athens,” based on cherry picked examples.

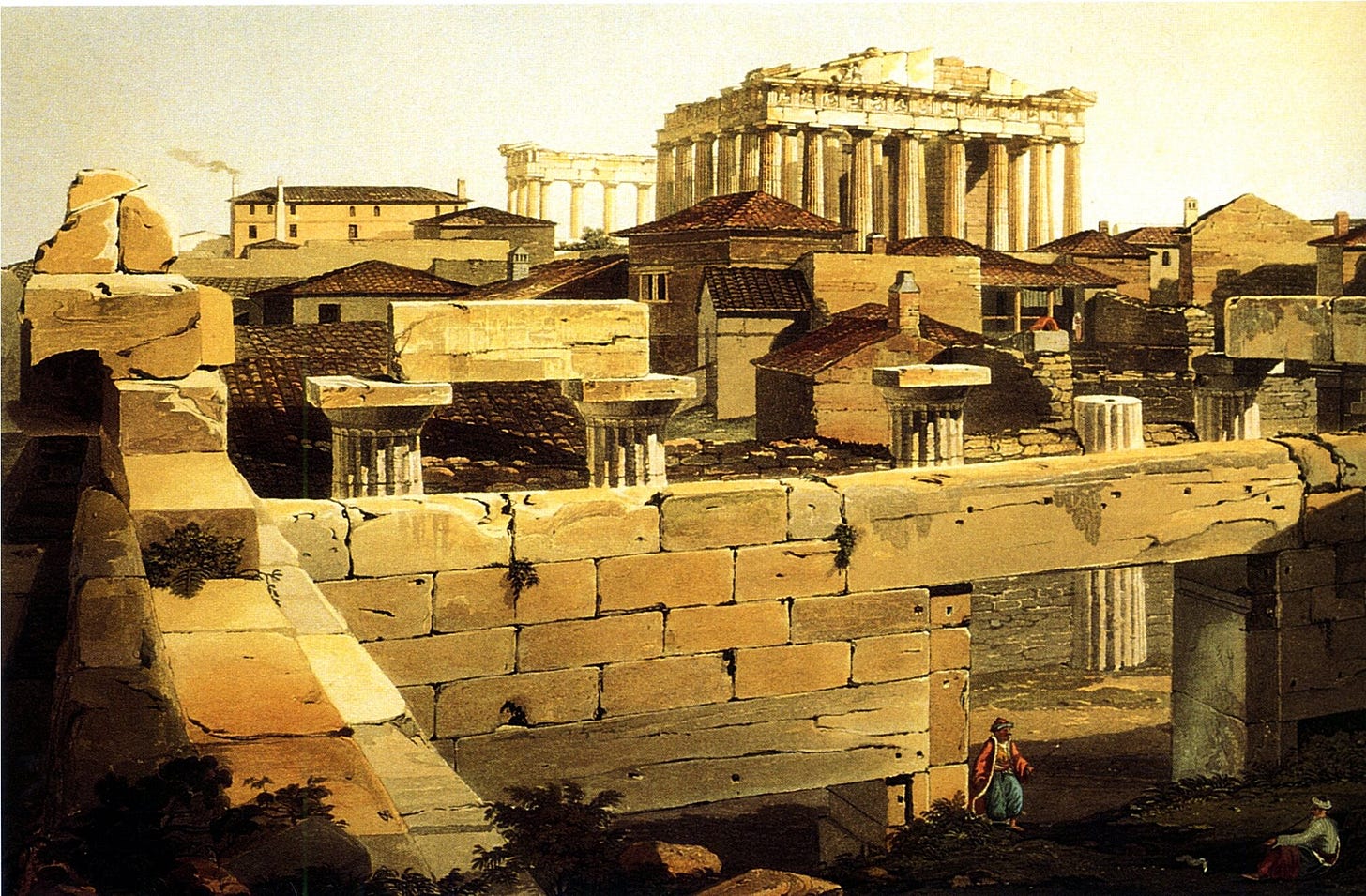

This renders (Modern) Greece guilty of erasing “Islamic history as a “co-presence” at the Parthenon and at Aya Sofia, among other European cultural sites, “in favour of the classical (and Christian) history.” The proposed solution is a shift towards telling the “simultaneous histories” of “cultural co-presences,” whereby Athens is to be understood as “an Islamic city" in the context of the Ottoman occupation, notwithstanding the narrow normativity of such a designation of a city under colonial oppression.9

A supporting argument states that “the classical ideal of Greece was ideologically colonised by European imperial powers in the form of Western Hellenism… [t]he imperial powers of the day… attempted to align the new Greek nation with their ideas and values, expecting it to simultaneously live up to their idealisation of classical Athens and their expectations of a Christian nation.”10

This is an accurate summation of the dynamics between Greece and the so-called West,11 but not of Greece itself: there is no such thing as Western Hellenism except in the collective imaginary of a portion of academia.

Nor can Athens be considered to ever have been “an Islamic city.” Apart from not being a city during the period under consideration, but a citadel encircled by frequently raided villages, one must also consider fluidities of its multicultural and multilingual nature, the ambiguous memories, conceptualisations of identity, and relations to place carried by indigenous Greeks, Slavs, Arvanites, and Jews in their interactions with each other and with the occupying culture; this is dynamically period-dependent and requires social anthropological input.12

We can certainly speak of it holding particular significance for Muslims in the context of Islamic memory of the Ottoman occupation, but this is where inclusion and acknowledgement of interaction can be integrated into historiography (as has been done in the virtual history tour in the page linked in the photo captions above) without essentialist labels that create new - and ahistorical - binaries. This harmonises well with a further point from Alexiou:

Martin Bernal’s controversial challenge to an idealised concept of the ancient Greeks permits us to take his argument in a different direction and to view the denigration of the Byzantines and modern Greeks on grounds of racial and linguistic “impurity" as a particular form of ideological bias designed to seal off the ancient Greeks from subsequent and lateral contaminations.13

Consequently, within valid criticisms of the disciplinary flaws within Classics (and related disciplines), we find unjustifiable dismissals of medieval, early modern and Modern Greek agency - and the scholars who call for its consideration - on the basis of “nationalism”.14

European neoclassical philhellenism spawned a European-led Romantic Hellenocentrism and early nationalist quests for continuity in honour of Greece’s “glorious past.”

This in turn encouraged what was indeed flawed scholarship by modern standards - initially encouraged by Western academia, subsequently criticised and used to justify the exclusion of Greek-authored scholarship alongside approaches seeking more nuanced understanding of the persistence of characteristics and elements that have both evolved, and endured through the centuries. The irony of this perspective is that that very Greek scholarship depended on German and French studies of Greek myth and history.

Ideological approaches of this nature largely ceased from the 1970s onwards, and modern Greek scholarship on historical and classical topics today reflects international academic standards.15 Nevertheless, it has marred the reputation of Greek scholarship ever since, and Greek scholars frequently experience a distinct racist bias when arguing this case.16 Serious scholarship countering these lenses has been in circulation for some years; however, it does not seem to have reached many of its neighbours, per the examples above.17

Long overdue efforts towards the decolonisation of Egyptology have been deservedly fruitful and may yet present a valuable precedent.18 Conversely, the treatment of Greek material deriving especially from the post-classical and Byzantine periods remains entrenched between persistent classicist romantic idealisation and hyperbolic accusations of Hellenocentrism.19 This leads to the genuine question: why is it not only acceptable, but celebrated when disciplines such as Egyptology, African Studies, and other disciplines applying critical theory20 disrupt Euro-American scholarly convention to refocus the discussion according to the indigenous conceptual frameworks that allow for a more accurate, thorough, and representative understanding of their material, but the same does not apply to Hellenic or Byzantine studies?

In early modernity part of the answer begins with Petrarch and not only the reception of Greek thought in the Renaissance, but also the scholarship thereof:

The modern myth that Greek intellectual life infused itself into the West only after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 has now largely disappeared, even from textbooks… Byzantines and westerners [sic] had been interacting for some time… The story of Hellenism’s transformation in Europe, from the fourteenth through to the sixteenth century, is a story of acquisition, appropriation, and domestication that began with Petrarch’s early and ultimately unrealised desire [to learn to read Greek].21

Unfortunately this “myth" has not disappeared at all.22 As a result, the romantic privileging of the classical Pagan world over subsequent iterations of Greek culture; and careless, patronising, or disingenuous perpetuation of received wisdom on outdated problematic examples as described above23 to evade this very discussion, have obscured core aspects of Greek culture, its historiography and meaning in anglophone scholarship, while maintaining a “static or idealised model of ‘Greece’”.24 Matters of hegemony and marginality cannot be ignored in this context.25

As the artist and critic David Batchelor writes in his 2000 book, “Chromophobia,” at a certain point ignorance becomes willful denial—a kind of “negative hallucination” in which we refuse to see what is before our eyes. Mark Abbe, who has become the leading American scholar of ancient Greek and Roman polychromy, believes that, when such a delusion persists, you have to ask yourself, “Cui bono?”—“Who benefits?” He told me, “If we weren’t benefitting, we wouldn’t be so invested in it. We benefit from a whole range of assumptions about cultural, ethnic, and racial superiority. We benefit in terms of the core identity of Western civilization, that sense of the West as more rational—the Greek miracle and all that. And I’m not saying there’s no truth to the idea that something singular happened in Greece and Rome, but we can do better and see the ancient past on a broader cultural horizon.”

Margaret Talbot, “Color Blind,” The New Yorker, October 29, 2018

Full article available here.

These broadest of brushstrokes cannot replace the necessary overdue analysis of these issues. I ask readers eager to cut to the chase to forgive this digression, but also to take it seriously. To address gaps in the scholarship of Hieroglyphica, culturally entangled practices and traditions26 and the agency “of both indigenous and intrusive groups” must be considered “through a carefully contextualised analysis of material cultural patterning and archaeological residues of practices.”

Both synchronic and diachronic approaches can bring much to the conversation: it is possible to assess “‘non-Greek” entanglements “at each stage of transmission without undermining the integrity of the language and culture as a whole,” reframing it as a topos of “interaction and inclusion rather than exclusion.”27 The Alexandrian milieu in which the Hieroglyphica, or elements of it, emerged, functions as a third ground of shifting hegemonies in which this degree of nuance is necessary. So too, does modern scholarly reception of such manuscripts, nowhere more visible than in the consistent neglect of the Byzantine lines of transmission.28

The book continues by situating the Hieroglyphica in the midst of its historical and cultural milieu, with a culturally sensitive exploration of the School of Alexandria, of which Horapollon was the penultimate leader.

Mathura Umachandran and Marchella Ward, “Towards a Manifesto for Critical Ancient World Studies,” in Critical Ancient World Studies: The Case for Forgetting Classics, M. Umachandran & M. Ward eds., Routledge, 2023, 3.

Written in the context of International Relations, the foundation for this is nevertheless especially pertinent. See Claudia Brunner, “Conceptualizing epistemic violence: an interdisciplinary assemblage for IR,” International Politics Reviews, Vol 9, 2021: 193-212.

Umachandran and Ward, “Manifesto,” 3-6.

This encompasses the Hellenic diaspora as well as the adoption of the modern Greek language, mentality, and way of life.

Herzfeld, Michael, “The Absent Presence: Discourses of Crypto-Colonialism,” South Atlantic Quarterly 101, 2002, 899–926; ibid., Cultural Intimacy, 25, 39, 71-2, 74, 137. The latter source especially explains the immense sociopolitical consequences of “the consequences of the contested but authoritative valorisation of Western culture in people’s daily lives.” (72).

See Hall, Hellenicity, op. cit; Cf. Aaron P. Johnson, Religion and Identity in Porphyry of Tyre: The Limits of Hellenism in Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press 2013, Ch. 1, for a meticulous analysis of the difference between Hellenocentrism as a mark of cultural power, and proliferating cultural exchange resulting in hellenization of cultural activity that did not involve power relations and cannot be subsumed under an essentialist label of ethnocentrism. In Irad Malkin ed., Ancient Perceptions of Greek Ethnicity, 2001, we find a valuable collection of studies interrogating the nature of cultural and ethnic self-identification in antiquity and the degree to which ethnicity was culturally determined in various locales. Likewise Glen W. Bowersock, Hellenism in Late Antiquity (Thomas Spencer Jerome Lectures), University of Michigan Press, 1990, for an early, but still valuable exploration of the texture and dynamics of late antique Hellenisation. Also T. Derks & N. Roymans, Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition, Amsterdam University Press, 2009 for useful perspectives on the study of material culture in relation to definitions of ethnicity and identity in antiquity.

See Yannis Stouraitis, “Is Byzantinism an Orientalism? Reflections on Byzantium's constructed identities and debated ideologies,” in Identities and Ideologies in the Medieval East Roman World, Y. Stouraitis ed, Edinburgh, EUP, 2022, 19-47. The references to this piece further reflect claims made above. Also see Przemysław Marciniak, “Oriental Like Byzantium: Some Remarks on Similarities between Byzantinism and Orientalism,” Alena Alshanskaya, Andreas Gietzen, Christina Hadjiafxenti eds., Imagining Byzantium: Perceptions, Patterns, Problems, Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 2018.

For example, in his recent book Hellenic Tantra, (Ch. I) Gregory Shaw writes: “To describe theurgy as “Hellenic Tantra” is thus a provocation and contradiction. Hellenism evokes the glory of Greece and the foundations of Western rationalism. Tantra is associated with superstitious Oriental rites and sexuality. To imagine Hellenism and Platonic philosophy as a kind of Tantra challenges our cultural identity as the heirs of Greek rationality.” Shaw uses Tantra throughout the book as a measure of comparison for non-dualist practices through which to better conceptualise Hellenic theurgy. Yet in so doing, he is placing a gloss on Graeco-Egyptian thought that immediately creates associations and connotations, while claiming for his Anglo-American audience a cultural identity “as heirs of Greek rationality.” He has not considered that the same non-dualism seen in Neoplatonism is familiar to Modern Greek thinkers and intellectuals, is present in Greek scholarship, is visible within Greek Orthodox practice, and that the Greek culture is heir to this by default in an inherently non-dualistic culture that is far more conversant with the non-dualist conceptualisation that is only just being perceived by Western scholars, as he notes in his narrative of the mis-reception of Neoplatonism in the West. Orthodox theology is adamant on the matter of non-dualism and does not accept matter as being lesser than spirit, as is seen in polemics against the Gnostics (Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses; Klemes of Alexandria, Stromateis VII, the work of Maximos the Confessor especially, and modern theological treatises; indicatively, Archim. Theophilos Lemontzis, “Gender Identities and the Gnostic Henophylia,” Pemptousia, 2018; F. Antonios Alevizopoulos, Occultism in the Light of Orthodoxy, Athens 1994. His narrative of auto-Orientalisation on the part of Iamblichos and parallel with Helena Blavatsky is even more problematic irrespective of whether it is simply a gloss for the convenience of readers, because it represents a presentist bias and comparisons that overlook the historical interactions and dynamics between these cultures.

Lylaah L. Bhalerao, “Away from “Civilisational” Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean: Embracing Classical and Islamic Cultural Co-presences and Simultaneous Histories at the Parthenon and Ayasofya,” in Critical Ancient World Studies, 156-171 (157-8). The author suggests that too often such Islamic histories are dismissed as untrue or misconstrued, arguing that what matters most is that “[Athens] belonged to different cultures at different points in its chronology, each with its own timeline and construction of the past.” She claims that this justifies its designation as “an Islamic city” under Ottoman occupation, irrespective of the fact that under Ottoman rule Athens was little more than a backwater and collection of villages. She continues by criticising “Greek nationalism” for “eradicating traces of Islam” as “the newly independent Greece wanted to extricate itself from any ties to their Ottoman conquerors.” (159-160). The author has a point regarding simultaneous histories; however the entanglements flow still deeper in cases where such histories involve a self-admitted oppressor (the Ottoman Empire) and a former vassal state (Greece). The millet system, the material history of Athens, or any locale with such “simultaneous histories” requires far more nuanced treatment. I feel that Alexiou’s elegant approach is a more balanced proposal addressing both sides of the equation. An example of simultaneous histories applied in practice without the need for such rhetoric: “Today one perceives a general reluctance among Muslim colleagues to be concerned with the Greek impact on their culture… But, within the framework of Muslim civilisation, the Greek heritage was more the continuation of an indigenous tradition, comparable to Oriental Christendom, and less the reception of something from outside. And the Greeks who settled around the Mediterranean were not Europeans in the modern sense of the word; moreover, there were authors of the Hellenistic age and the Roman Empire who wrote Greek but ethnically were not themselves ‘Greek.’ All modern European ideologies that left their successive imprint on intellectuals in the Orient conveyed the idea that the Greeks had been the spiritual ancestors of the Europeans only.” Gotthard Strohmaier, “The Greek Heritage in Islam,” in The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, 140-149 (148). A focused argument on this point is found in Herzfeld, Michael, A Place in History: Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Town, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Bhalerao, “Simultaneous Histories,” 161; citing Greenberg and Hamilakis, 2022, 11; Herzfeld, 2002.

Taken here to signify the Great Powers of the nineteenth century.

Bintliff, J.,“The Ethnoarcheology of 'Passive' Ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece,” in The Unusable Past: Greek Metahistories, K. S. Brown, Y. Hamilakis eds. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2003; Simeon Spyros Magliveras, “The Ontology of Difference: Nationalism, Localism, and Ethnicity in a Greek Arvanite Village,” PhD thesis, Durham University, 2009. Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/248/; Evdoxios Doxiadis, State, Nationalism, and the Jewish Communities of Modern Greece, Bloomsbury, 2018.

Alexiou, After Antiquity, 2; cf. Bernal, M., Black Athena: The Afro-Asiatic roots of classical civilisation. London: Free Association Books, 1987; Trenton, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

Which really should be laid to rest in view of modern scholarship. Cf. Alexiou, After Antiquity, 13; Anthony Kaldellis, The Case for East Roman Studies, ARC Humanities Press 2024 (forthcoming); Makrides, Hellenic Temples, op. cit.

As is evident from the quality of work in the public repository of doctoral theses at www.didaktorika.gr; as well as that emerging from Hellenic Studies centres. The language barrier prevents wider dissemination of these; one queries why Modern Greek continues to be dismissed as a language for scholarly communication.

Alexiou, op. cit., Kaldellis 2012., op. cit., Herzfeld, op. cit., Hall., op. cit. Cf. Rachel Yuen-Collingridge, “Forgery as decolonisation: Constantine Simonides in Liverpool,” in Blouin & Akrigg eds., The Routledge Handbook of Classics, Colonialism, and Postcolonial Theory, Routledge 2024, 487. This has also been my own experience as a British-Greek scholar among some British, Northern European, and American academics.

For example, Kaldellis, Byzantine Readings, op. cit.; ibid., “The Byzantine Role in the Making of the Corpus of Classical Greek Historiography: A Preliminary Investigation,” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 2012; 132:71-85; Elizabeth Jeffreys, “We need to talk about Byzantium: or, Byzantium, its reception of the classical world as discussed in current scholarship, and should classicists pay attention?, Classical Receptions Journal, Vol. 6(1), Jan. 2014, 158–174; Herrin J, Unrivalled Influence: Women and Empire in Byzantium, Princeton University Press, 2013.

Indicatively: Carruthers, W., Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary measures, New York and London: Routledge 2015; Colla, E., Conflicted antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptian modernity, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007; Christian Langer & Uroš Matić, “Postcolonial Theory in Egyptology: Key Concepts and Agendas,” Archaeologies, Vol. 19 (2023): 1-19.

For example Martin Bernal, “The Afrocentric Interpretation of History: Bernal replies to Lefkowitz,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 11 (Spring 1996), 86-94. It is unthinkable to deny the Egyptian influence on Greek civilisation, or the cultural exchange beyond recorded history, acknowledged by Herodotos and Plato, well-documented by later authors, or indeed the multiculturalism of the broader Greek-speaking world of late antiquity. I agree with Bernal on most points of Egyptian influence, as well as bias in the Classics upholding Greek rationalism as the highest ideal. My objection is with those who have taken Bernal’s ideas to extremes, casting cultural exchange (in whichever direction) as theft (“stolen legacy”) or fabrication ultimately laid at the feet of ancient Greeks rather than inaccurate modern scholarship. Bernal does not do this; other scholarship has unfortunately done so. Cf. Saif above. A further reason for highlighting this debate is the ongoing exclusion of Greek scholarship from academe or specific disciplines on the basis of accusations of “nationalism,” or ethnocentrism, even as agency is finally hard-won by other excluded groups. As the foregoing should demonstrate, my argument is against romanticised classical idealisation and essentialism overall.

Also see the recent book by Jørn Borup, Decolonising the Study of Religion: Who Owns Buddhism?, Routledge 2024; cf. J. Borup, “Who Owns Religion? Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Cultural Appropriation in Postglobal Buddhism,” Numen 67 (2020), 226-255.

Christopher S. Celenza, “Hellenism in the Renaissance,” The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, Oxford University Press 2009, 150-2 (151-2), citing Petrarch, quoted in M. Cortesi, ‘Umanesimo Greco,’ in Lo spazio letterario de medioevo, 1. Il medioevo latino, vol. 3: La ricezione del testo, 457-507, G. Cavallo, C. Leonardi, & E. Menestò eds., Rome, 1995, 457. Here one might also mention the fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople; long prior to this, the many tensions between Byzantium and the West in the sense of the Holy Roman Empire and the Great Schism as dynamics underlying the often hostile treatment of Greek-speakers in the West on religious, cultural, and indeed, power-related grounds. Indicatively, see Nikolaos G. Chrissis, Athina Kolia-Dermitzaki, and Angeliki Papageorgiou eds., Byzantium and the West: Perception and Reality (11th-15th C.), Routledge 2019. It is crucial that Western scholars understand the dynamics and impact of these factors, not as isolated historical events, but as synchronic and diachronic lenses that have affected their own perception of this material.

There are several more historical reasons as to why, which I hope to address in future work. Cursory references to Michael Psellos and Georgios Gemistos Plethōn, are tokenisms that do not resolve this.

Yuen-Collingridge, “Forgery,” 487; Cameron, The Byzantines, 177; Herzfeld, Cultural Intimacy, 127-9.

Alexiou, After Antiquity, 13.

For an excellent analysis of the broader sociopolitical context for such attitudes towards Greece and Greeks in relation to Euro-American narratives, see Herzfeld, “Chapter 6: Cultural Intimacy and the Meaning of Europe,” in Cultural Intimacy, 120-138. Cf. Yannis Hamilakis, “Indigenous Hellenisms/Indigenous Modernities: Classical Antiquity, Materiality, and Modern Greek Society,” in G. Boys-Stones, B. Graziosi, Phiroze Vasunia eds., The Oxford Handbook of Hellenic Studies, 2009, 19-31 (25).

Bernd-Christian Otto, “Introduction: Western Learned Magic as an Entangled Tradition,” Entangled Religions, 14(3), 2023.

Alexiou, After Antiquity, 13.

Buzon, M. R., Smith, S. T., & Simonetti, A, “Entanglement and the formation of the ancient Nubian Napatan State,”American Anthropologist, 2016: 118, 284–300. Matić emphasises: “Contrary to relational entanglement, material entanglement “signifies the creation of something new that is more than just the sum of its parts and combines the familiar with the previously foreign. This object is more than just a sum of the entities from which it originated and clearly not the result of local continuities.” Stockhammer, Ph. W., “From hybridity to entanglement, from essentialism to practice, Archaeological Review from Cambridge,” 2013: 28(1), 11–28 (16) in Matić, “Reverse Discourse,” op. cit. Third space is any encounter in which ambivalent meanings are formed through communication between the “I” and the “you,”’ and does not refer to physical space. On “third ground” and “hybridity” in the context of postcolonialism see Homa Bhabha, The Location of Culture, Routledge 1994; on their limitations see Acheraïou, Rethinking Postcolonialism, 40-54. Bhabha is referring to the construction of cultural artifacts as “a political object that is new, neither the one nor the other… a disturbing questioning of the images and presences of authority.” (25; 113) This is identified as “a subversive strategy, mimicry of the authority for the sake of its questioning.” However, cultural hybrids in archaeology and the history of material culture possess a broader meaning: “visual hybridism… cosmopolitanism… cultural mixing,” which are sometimes problematic in themselves when such labels are the product of assumptions thereby concealing the input and power relations between cultures (Matić, “Reverse Discourse,” op. cit.). The differentiation between uses of the word “hybrid,” and the nature and quality of historical entanglements in the archaeological/historiographical usages are as relevant to texts as they are to material culture, as emphasised by Matić further in his analysis.

Thank you for your remarkable work🙏. I've now realized 'cultural co-presences' is not just a combination of wordsyou can find in pannel, but a meant approch to history.

I think you are absolutly right about Renaissance.

At the beginning, I suppose Italian Peninsula politicians proposed themselves as rescue-team to Romaioi's Empire to preserve their gained though centuries influence, certifying their action by blood affinity (I'm thinking about the Piedmont Crusade in 1366 or about the fresco cycle of the 'Torneo dei Cavalieri', by Pisanello, in Mantua Castle, recently proposed to depict Cleophe Malatesta as the daughter of king Brangoire, mother by trick to Hélain;) le Blanc, future heir to the Constantinopolitan throne). Later, much more champions without blemish and fear wanted to join the quest and resolved to pretend cultural affinity if not blood one.

You masterly explained about Carolingian and Othonian agenda in other works, and - may be it's just an idle idea of mines - I suspect even a Norman segment in the plot, undergoing from Abbey Du Bec school to Grosseteste translations of Eustrathius of Niceae and Michael of Ephesus works about Aristotle:)

How dare we question the goodness of the western project and how it brings enlightenment to those places not deconstructed and dislodged from actual culture with roots! How dare we not accept the secular western categories and phronema (it’s globalizing imperative)! How dare we value roots and traditions and customs and values which have not been “sanitized” by modernity and post-modern and the empire of Western academic modes of thinking. And how dare we value the culture that gave us democracy, philosophy (much of which is superior to the post Cartesian elimination of formal and final causes and Ockhams rejection of universals)! No to question our narrative of progress and showing with critical theory the ontological violence perpetrated by every historical civilization!

Nothing would be sadder to me than if the west wins out in Greece, because as use it stands it seems as the last example of being still at least mostly a not completely westernized nation. Philosophers (not just theologians) there like yannaros have drawn on Maximus the confessor to dialogue and offer an alternative to Heidegger.

And for Orthodoxy watching the sense of identity the orthodox displaced from Russia at the St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute France, had as possessing a different phenomena and approach to theology being lost to the academy and its categories (with the American Orthodox losing touch with roots and phenomena as well makes me worried) that we will lose the preservation of any episteme and phronema but that of the western project altogether.

And the irony is that every native population that enters into the global economy and has been reached by Protestant missionaries and had western education imposed upon them (like many in Alaska who became orthodox but without being required to modernize or become or speak Russian) end up suffering from alcoholism and depression and very high rates.

No, we Anglo-Americans and Western Europeans have protected our narrative of progress with its constant unfulfilled promise by turning against the past and the sins we now are fixing with absurd and irrational forms of theory.