How to pronounce the Voces magicae in ritual

Their transmission by angels, and the hard evidence

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

This article was inspired by a request for assistance with Greek pronunciation from Frater RC and fruitful discussions with Dr and . It is also partly inspired by a couple of American Classics scholars engaged with translating the Greek Magical Papyri who made unjust accusations regarding my motivation when they had also requested my assistance, and I had pointed out that there is no justification for the ongoing misuse of a living language and misrepresentation of its culture. I am grateful to the Biblical scholars in particular who have substantiated this argument beyond question.

Enjoy the free content but currently unable to subscribe?

Subscribe to the free plan to receive updates and free articles, or the paid plan to access exclusive content!

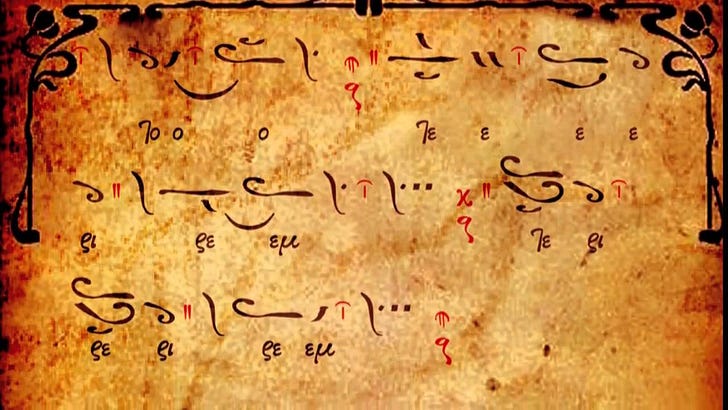

I freely admit to being a long-time skeptic when it comes to modern practices based on the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) and ritual performance of magical calls as found in some esoteric ceremonial orders, especially when it comes to use of vocalisations such as these:

The reason for my skepticism is neither, as some may assume, scholarly bias, nor my perennial displeasure at the disrespect and belittlement of modern Greek.

It begins with the convoluted discussions of what is meant by instructions such as the following regarding pronunciation:

the “A” with an open mouth, undulating like a wave; [A, α]

the “O” succinctly, as a breathed threat. [O, ο]

the “IAÔ” to earth, to air, and to heaven. [ΙAΩ, ιαω]

the “Ê” like a baboon; [Η, η]

the “O” in the same way as above; [O, ο]

the “E” with enjoyment, aspirating it, [Ε, ε]

the “Y” like a shepherd, drawing out the pronunciation. [Υ, υ]PGM V. 24 – 30

Such descriptions have sparked any number of online debates on whether to pronounce the vowels this way or that, what a shrieking baboon might sound like, and whether the indication for ‘Y’ should echo panpipes or a sheepdog howl. I have seen some quite preposterous suggestions and attempts to “divine” the correct pronunciation that go to great lengths to ignore the actual, living, spoken Greek language of today, with various arguments attached.

If we explore the actual language as it has been spoken, sung, and evolved since late antiquity, we might come far closer to something resembling the “original” pronunciation and use of such incantations, hidden in plain sight.

A key point to bear in mind is that we are not debating the pronunciation of Classical Attic Greek (the version arbitrarily applied by some scholars to represent all of Greek speech in antiquity, largely regardless of region and period), but of Hellenistic Koine in Egypt and Asia Minor: two forms of pronunciation as disparate as those of (modern) Glasgow vs. New York, to provide but one analogy.

While there is clear historical evidence for the prosodic nature of Attic Greek, it is as bizarre to propose the Erasmian reconstruction of this particular variant as the only authentic pronunciation across Greek-speaking regions and periods, as it is to propose that all historical English should henceforth be spoken in a reconstructed version of Chaucerian or Shakespearean English (prior to the Great Vowel Shift):

And whereas Greek pronunciation has certainly changed since the time of Plato, there is tangible evidence that beyond regional dialect variations and standardisation (in the vein of English Received Pronunciation) during the 20th century; a practice found across many modern nations, it has not changed essentially since the time of Alexander.

Nor has it entirely lost its prosodic nature, as can easily be heard in Cretan, Cycladean, and Ionian dialects, still spoken to this day (I speak the latter in certain circumstances, the same way a British person from Newcastle might speak Geordie with friends, but attempt something closer to RP if presenting the news).

Warning for Greek-speakers: there is some quite salty language used in this clip, but it’s the only one I could find of the Corfu dialect that’s authentic rather than staged. For non-Greek speakers, listen to the rhythm and lilt.

Cretan dialect spoken in the Greek village of Hamidie in Syria, created by the forced expulsion of Cretans by Sultan Abdul Hamit in the 19th century. Their descendants still live there and still speak with a distinctive Cretan dialect.

Since the PGM date from well after the time of Alexander, and their many variants span seven centuries of potential composition and usage, “Modern” (more correctly, “Historical”) Greek provides a far more accurate guide to the Greek phonetic spelling of the early centuries CE, than does any attempt to rationalise use of the Erasmian system or otherwise, as is now widely accepted among Biblical scholars, who study the use of Greek from precisely this period (see this video and the footnote).1

Aside from lengthy tomes with difficult phonetic notation, we have concrete evidence for the pronunciation and enunciation of sacred vowels in the one place that practitioners may prefer not to look, but which nevertheless provides a valuable repository.

Every Greek has grown up with these sounds echoing as a soundtrack to the ritual year.

Have a listen before reading further, and note the vowels and how they are articulated. The markings seen below are Byzantine musical notation, known as nevmata. The word is pronounced NEV-mata and not “neumata” because by the Byzantine period the diphthong “eu” had already acquired its “ev-ef” sound):

The association between Greek vowels, the celestial bodies, and the deities they represent is long-established, so too is the Pythagorean basis for these connections.2

Less well understood in the English-speaking world are the connections between Pythagorean musical theory, the nomina barbara of the PGM and related texts, and Greek Orthodox hymnal chanting.

Voces Magicae with their attendant gestures and correspondences are not only found in mysterious papyri; they are embedded in the Orthodox liturgy too; for their source is one and the same: hieratic practices born of Graeco-Hebrew-Egyptian syncretism in late antiquity.

Known as monodic or monophonic (with a single line of melody), Byzantine music rests on a system derived directly from Pythagorean theory and a system of harmonics (αρμονικαί) inherited from Ancient Greek music.3

Even in times of great upheaval and religious change a civilization does not simply vanish, especially not its cultural accoutrements such as art and music. These two elements (theory and notation in the case of music) comprise valuable material evidence of precisely what sacred vowels should sound like.

Music and metaphysics

As early as the 5th-4th century BCE, Greeks had elaborated what is known as the Greater Perfect System (σύστημα τέλειον) of music; a system of harmonics and intervals based on Pythagorean mathematics, that give us the octaves and notes that evolved in Western music. The Greater Perfect System corresponded to colour, geometry, and the planets, and these correspondences later came to be reflected in the magical use of voice and harmonics, on which more below.

It was later elaborated and subdivided by Aristoxenos into what are known as octave species, to reflect regional differences in how music was played in different regions, giving rise to the various modes (Lydian, Phrygian, Dorian, etc), named for the regions where they predominated. What distinguishes these are the base pitch (the note from which counting the octave starts), and the intervals between the notes.

Crucially, these modes were considered to reflect both emotions and characters, per Aristotle:

But melodies themselves do contain imitations of character. This is perfectly clear, for the harmoniai have quite distinct natures from one another, so that those who hear them are differently affected and do not respond in the same way to each. To some, such as the one called Mixolydian, they respond with more grief and anxiety, to others, such as the relaxed harmoniai, with more mellowness of mind, and to one another with a special degree of moderation and firmness, Dorian being apparently the only one of the harmoniai to have this effect, while Phrygian creates ecstatic excitement. These points have been well expressed by those who have thought deeply about this kind of education; for they cull the evidence for what they say from the facts themselves.4

Both Plato and Aristotle considered musical education of youth crucial to moulding a solid character and ethos, while Neoplatonists such as Proklos and Iamblichos specified the types of music appropriate for the gods and for humans respectively.5In his commentaries on Plato’s remarks on music, Proklos connects Neoplatonic metaphysics to the harmonic scale, considering it to be a mirror of the World Soul as elaborated by Plato in the Timaios, and Aristotle in On the Soul.

Following Aristotle, Iamblichos goes further in connecting the geometrical (and harmonic) intervals with the spiritual faculties, building in both cosmological, and gnoseological dimensions and effects, which he elaborates whereby the rays of Helios produce a vibration in the ether that equates to music; so too, do the other celestial bodies.6 Reflections (and probably sources) of these concepts are found in the Hermetic Nag Hammadi treatise Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth (Nag Hammadi Codex VI), convincingly argued to be a fusion of “popular Greek philosophy and indigenous Egyptian traditions.”7

Also in his commentary on Plato’s Republic,8 Proklos highlights the connection between the single human voice, and the essential life of the soul. Correct practice of these harmonies reflects a harmony of the spheres through which the souls travel, and Proklos notes that:

In this sense the voice of the Sirens related to vocal music is related to hieratic art, which is linked to life. The Hymns to the gods, based on the seven vowels, says Proclus, sung in the opportune moment help to preserve the harmony between the life of the cosmos and human life, and the hieratic point of view surpasses the mathematical and dialectic points of view. According to this, it is important to see the symbolism of a single phônê expressing a unitive noeric life (in a similar way the cicadas and the birds express living sounds, which are natural rather than instrumental sounds.9

Distinguishing four levels, or registers of music, from the “therapeutic and educational” which is required for the earliest cultivation of the spirit, through to Symmetry which mirrors intellect, Beauty which mirrors Life, and Truth, which mirrors Unity, these correspond to the Neoplatonic notions of Mikton (Harmony of Created Manifestation); Apeiron (Divine Infinite Possibility); and, Peras, in transcendence of both Essence and Truth. 10

From Proklos to Byzantine Music

The adoption of Christian faith in the Greek-speaking world was neither sudden nor monolithic, and cultural practices continued largely as before, with the exception of official polytheistic worship, which also altered by degree and not in one fell swoop. Existing techniques and practices were adapted to the new faith, but as exhaustively argued elsewhere,11 the theology and metaphysical concerns drew strongly on Neoplatonist thought (on which more in a future offering).

The earliest composers of Byzantine hymns used the musical system they already had, and developed the οκτάηχος: a system of eight tones identified with the modal octave species of Aristoxenos, in turn developed from Pythagorean theory. Though the notation is more recent (tenth century), that is simply a technology for recording and teaching the music, not a new system.

Reception in the Latin West was considerably different, and did not make use of Pythagorean concepts. This need not concern us beyond the consideration that differing frames of reference in relation to musical theory may also be a hindrance in grasping some of these points.

Records of early Byzantine (or Late Antique: 4th-9th centuries) liturgical chants as well as secular (court ceremonial, drama, and pagan) music are well attested and survive in the writings of Church Fathers and preserved manuscripts; some acclamations and hymns from these periods remain in use today.12This is our evidence for the fact that the music that has reached us, and the way it is sung, derives from these early roots.

Most important of all, however, is the strong conviction that music derived from sacred chants transmitted directly by angels to humanity; a belief that lay at the heart of Byzantine liturgy.

Drawing on Scriptural sources13 and Jewish beliefs, this doctrine is also well attested in the Patristic literature, including John Chrysostom, Pseudo-Dionysios, Justin Martyr, Athenagoras, and others, as well as later Byzantine writers Nikolaos Kavasilas and Symeon of Thessaloniki.

Although early liturgy featured choirs of the faithful reflecting communion with the heavens via liturgical chants in the tradition of the Ancient Greek χορός (chorus), this was abandoned in later centuries, with trained and dedicated psaltai (chanter, with strong influences from Jewish ritual chanting) replacing the more participative choir of the faithful.

Orthophony and correct vowel enunciation is key to the training of psaltai, and they sound just as heard above, in the Triumphal Liturgy from the Liturgy of Basil the Great (of Caesarea, 4th century CE). This is one of the oldest hymns still used in Orthodox liturgy, set to an Archaic melody, in the Second Echo of the octaechos which corresponds to the Phrygian Mode.

The following example, known as Χερουβικόν (Hymn to the Cherubim), in the same mode, is an invocation of the angelic hordes and is sung while the Communion bread and wine are being brought out of the sanctum, while the priest swings the censer and prays rhythmically, speaking his own public confessional of metanoia. According to Byzantine exegetes, it is thought that during this hymn, angels join their voices with those of the congregation, and the gates of heaven itself open for direct communion.

There are four different versions depending on the date within the ritual year. It begins: “We who secretly [create the image of] the cherubim and chant to the life-giving Trinity the thrice-holy hymn, let us now abandon every earthly care to receive the King of all, who is invisibly joined by the angelic hierarchy.”

The reference to “secretly creating the image” relates to the “disembodied” nature of the Cherubim, who are among the highest in the angelic hierarchy (following pseudo-Dionysius), and whose image is not/cannot be described beyond that they are creatures of divine flame that may only internally (νοερά) envisioned, and are depicted as seen below, similar to the Seraphim who are the highest ranking angels.

This is one of the more overtly mystical practices within the liturgy. I invite readers to listen while observing the use, enunciation, and melody of the vowels. Close your eyes and imagine what a creature of divine fire with wings covered in eyes really looks like. If you imagine yourself in its presence you have a sense of the power of the process.

Back to the Voces Magicae

Voces Magicae with their attendant gestures and correspondences are not only found in mysterious papyri; they are embedded in the Orthodox liturgy; for their source is one and the same: hieratic practices born of Graeco-Hebrew-Egyptian syncretism, and believed to be a crucial channel for direct communion with the divine.

Sources such as the PGM, Solomonic grimoires, or the Kyranides are quasi-folk sources of this material, encompassing a hefty chunk of Egyptian temple wisdom with Hermetic elements, syncretised and Hellenised, Hebraised, or further adapted, depending on the region.

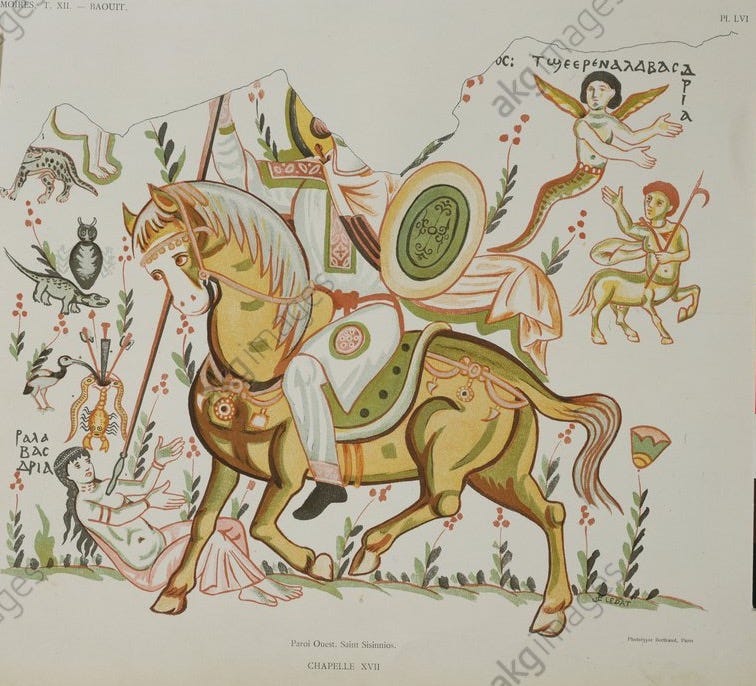

Material evidence helping us better visualise these common sources and parallel evolution is found in amulets and frescos that range from the Coptic temple at Bawit depicting St. Sisinnios vanquishing the demoness Alabasdria, who is identified with other female she-demons such as Gylou, or Abyzou, all encountered in such sources, and across lands where Byzantine influence reached.14

The relevance of this example is in the incantations that accompany it, that are both geographically and temporally widespread.

In folk magical sources we encounter many of the same calls, prayers, exorcisms and nomine barbara as we do in bona fide church hymns, kontakia, or quick blessings such as the Trisagion of Dynamis (Thrice-Blessing of Strength, see below), which is believed to be the oldest of all Orthodox prayers, found also etched on late antique amulets right alongside Gnostic or Hermetic elements.

We also encounter words of power and talismanic abbreviations imbued with power, as once seen on amulets and still seen on icons. The theology of icons provides much by way of explanation for the magical power of images; especially engravings or reliefs, since they act as vessels and repositories (this will be the topic of several future offerings so I will not elaborate at present).

One of the main differentiations between the “official” and the “folk” applications is the individualised use of such methods and the emphasis on the individual practitioner (with or without a community) as opposed to communal ritual and communion led by an officiant of the official religion; however, there is little to distinguish many of the practices themselves in terms of their purpose: the aversion of evil, the provision of sustenance and strength, and divine illumination.

In this regard, Orthodox liturgical tradition is one of the richest possible repositories for an approximation of how these practices may have been implemented, and nowhere is this more visible than in the liturgical use of melodic vowels, complete with turning to the four quarters, ritual gestures, use of incense, water, even specific plants in the ritual context.

The Orthodox communion service, among others, features aspects of overt theurgy, practiced communally, with the intentional selection of musical modes to induce specific emotional and mental effects. One need not be faithful to experience these, but I would challenge any practitioner of such rituals to sit through a service and fail to sense this.

Without prejudice

In the West, many polytheist sympathisers and believers have come to dismiss Christian practices out of hand, and I know they may find this piece challenging. Outside Greece and perhaps some other Orthodox countries, very few are familiar with the vast differences between Orthodox and other Christian practices.

In addition, the nature of the transmission of “Greek learning” to the Latin West has created a misperception that the only aspects of worth within Greece died out with the Classical era. Yet as I hope to have begun demonstrating through this newsletter/blog/journal, the evolutions of late antiquity as well as the Byzantine world merit a much closer look, through a lens that lays aside the prejudices of the past, whatever they may be, and that also challenges the boundaries between disciplines and scholarly concepts that have until now placed a false dichotomy between religion and magic.

There is much evidence within those aspects of official as well as folk religious practices that can shed light on those practices that today many believe to have been forgotten, lost, or dismissed by living traditions: I invite readers to join me in their exploration.

© Sasha Chaitow, 2025

The video and information in it is excellent, bar one point where the speaker claims (timestamp 6:16-6:24) that it doesn’t really matter how you pronounce Greek if you’re not using it as a living language. It matters, because the continued mispronunciation carries strong hegemonic implications towards Modern Greece and its people, and the continued misrepresentation of both language and culture. I have a lengthy section on this in my upcoming book. See a relevant excerpt here:

The Problem with Classics

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

Also see Philemon Zachariou, Reading and Pronouncing Biblical Greek: Historical Pronunciation versus Erasmian, Wipf and Stock 2020.

https://via-hygeia.art/charles-francois-dupuis-from-origin-of-all-cults-of-the-seven-greek-vowels/ Also: Joscelyn Godwin, The Seven Vowels, Phanes Press, 1991; Joscelyn Godwin, The Harmony of the Spheres: the Pythagorean Tradition in Music, Inner Traditions, 1992.

Landels, John G. (2001). Music in Ancient Greece and Rome (1st ed.). Routledge.

Politics (viii:1340a:40–1340b:5)

Mathiesen, T.J. (1999). Apollo's Lyre: Greek music and music theory in antiquity and the middle ages. Publications of the Center for the History of Music Theory and Literature. Vol. 2. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

Moro Tornese, S. (2010). Philosophy of Music in the Neoplatonic Tradition: Theories of Music and Harmony in Proclus' Commentaries on Plato's "Timaeus" and "Republic". [Doctoral Thesis, Royal Holloway, University of London], 226-7; Proklos, Commentary on Plato’s Republic, II, 65.15; 64.5-66.21. He further highlights the role of both Muses and Sirens in this process.

ibid., 234.

I have dedicated a lot of space to this in my commentary to Horapollon’s Hieroglyphica; a relevant excerpt serving as an example is here, a second one here, and an article not in the book is here. Also see M. David Litwa, How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths, Yale University Press, 2019.

Exodus 25; Isaiah 6:1-4; Ezekiel 3:12; Revelation 4:8-11.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365090047_From_Written_to_Oral_Tradition_The_Survival_and_Transformation_of_the_St_Sisinnios_Prayer_in_Oral_Greek_Charms - https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334190126_St_Sisinnius%27_Legend_in_Folklore_and_Handwritten_Traditions_of_Eurasia_and_Africa_Outcomes_and_Perspectives_of_Research

Absolutely fantastic Sasha, thank you.

This is excellent - thank you for the credit at the start!