The Pagan Answer to Jesus?

Apollonios, hagiographies, and the importance of the Greek biography genre

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the whole post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

Part of what follows is excerpted from my book “The Hieroglyphics of Horapollon: A New Translation with Commentary and Notes,” forthcoming from Black Letter Press later this year; the remainder is written exclusively for Thyrathen.

In the late second century CE, Roman Empress Julia Domna, the daughter of an Arab pagan priest of Elagabalus and wife of Septimus Severus, commissioned the sophist Philostratos to write the biography of the philosopher Apollonios of Tyana (first century CE). It has been suggested that the biography was commissioned by the Severan court as a piece of Pagan propaganda, possibly with the aim of countering early Christianity by producing a “pagan messiah”.1

Apollonios was a real historical figure and Pythagorean philosopher who lived around the time of Christ. Philostratos presents him as a divine, miracle-worker who, at the end of his life, ascended to heaven from the sanctuary of Dictynna in Crete.

Claiming to know little of Apollonios himself, Philostratos claims to have had access to the (probably fictitious) diaries of Damis,2 disciple and companion of Apollonius. Relating his travels around Asia, as far as India, Ethiopia, but also Italy and Spain, the book is replete with tales of his virtuous life and deeds, medical, magical, divinatory, and philosophical accomplishments, while there is some evidence that his cultic worship began in his lifetime, both in Tyana and further afield.3

Though Julia Domna did not live to see its completion in around 220 CE, the impact and influence of Philostratos’ The Life of Apollonios (more correctly, In Honour of Apollonios)4 was colossal, as she no doubt intended. Her son, the emperor Caracalla, and grandson, Severus Alexandros, both worshipped Apollonios within their personal sanctuaries, while Caracalla also erected a shrine to him in Tyana. He was depicted on fourth century coins and medals, and a fifth century epigram from Mopsouhestia (Cilicia) lauds him as “one ‘named after Apollo’ who ‘extinguished the errors of men’ …and… was taken up into heaven ‘to drive out the sorrow of mortals.’”5

The book was widely circulated and provoked a broad range of reactions among Christians of the period: some upholding Apollonios as an embodiment of Greek “ancestral culture” and preferring him as a comparison to Christ in contrast with Jupiter; others riposting against his admirers in disgust.

In the third century, Porphyrios and Hierocles compared Apollonios to Jesus; multiple Christian and Pagan thinkers argued over his nature, variously as a “disgusting" magician “polluted by sorcery;”6 or as a semi-divine “icon of a supposed ‘pagan resistance’ to Christianity” and an “exemplar of philosophical Hellenism.”

The early Christian counter-offensive to Apollonios’ posthumous fame is mainly found in Origen and Eusebius among others, who dub him a “magician” and “philosopher" who consorted with demons to distance him from the “true” miracle-worker, Jesus.7

In later centuries, among Latin Christians Apollonios came to be seen more as a cultural hero and dubious mage, but his Byzantine reception is more curious. An anonymous work known as the Apotelesmata of Apollonios of Tyana on the astrological workings of Apollonios, tallies with references in Philostratos to certain books on astral prophecy. Photios of Constantinople, the ninth century archbishop and book collector who contributed significantly to the first Byzantine Humanist Renaissance writes almost admiringly of Apollonios himself as a figure “leading a philosophic and temperate life, in which he exhibits the teachings of Pythagoras, in both manners and doctrine.”8

Holy-Man biography and its place in Greek thought

Beyond its role as a piece of pagan propaganda, the Life of Apollonios is a prime example of the “holy-man biography” genre of late antiquity. This genre has deep roots in the fifth century BCE, and developed as a differentiation from the historical works that began evolving at around the same time.

Whereas histories tended to focus on military and political developments following Thucydides,9 biographies occupied a special place in antique literature. Idealisation of the figure described was common, especially in the case of philosophers, and by the Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman period the hagiographical, panegyric nature of biography became its hallmark. Though this has sometimes been criticised by scholars, a new understanding of its role in Greek society, culture, and religion has since developed: these biographies played very specific roles:

Biographies like Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Porphyry’s Lives of Pythagoras and Plotinus, and Eusebius’ Life of Origen all serve an old typological interest: the traditional sage of philosophy. But this venerable figure had been transformed by the religious temper of the times and was endowed with specific qualities and talents linking him to divinity. A mythology of the holy man could be used by the philosophical schools because philosophy itself, which had once resisted the incursions of religious speculation, came increasingly to denote the search for God.

Thus while biography had formerly been used in the battle of school against school, it was now used by cult against cult in the rivalry between paganism and Christianity, a rivalry whose intensity had reached a feverish pitch by the time these biographers were writing. Scrambling to gain adherents, each side produced biographies of its “patron saints” in an endeavour to crystallise belief and so win converts. One only has to consider the amount of space given over to discussions of disciples, teaching methods, and publications in biographies like Eusebius’ of Origen and Porphyry’s of Plotinus to understand that they are a form of propaganda for a way of life and body of beliefs.10

Somewhere between myth and legend, holy-man biographies were lives writ large, the desirable virtues exaggerated and stylised to capture the essence, or spirit of the individual, but also to function moralistically, didactically, much like archaic heroic epics, “with the voice of myth… negotiating the intersection of the human and the divine.”11

There is much we can learn from this vantage point: firstly, what attributes were valued by the given community - philosophical, Christian, pagan, Greek, Hellenistic, Graeco-Egyptian, Byzantine - from which these hagiographies emerged. In turn this tells us much about the concerns of the era, as we discover from the Life of Apollonios upheld as a serious contender for the role of a Hellenic Messiah.

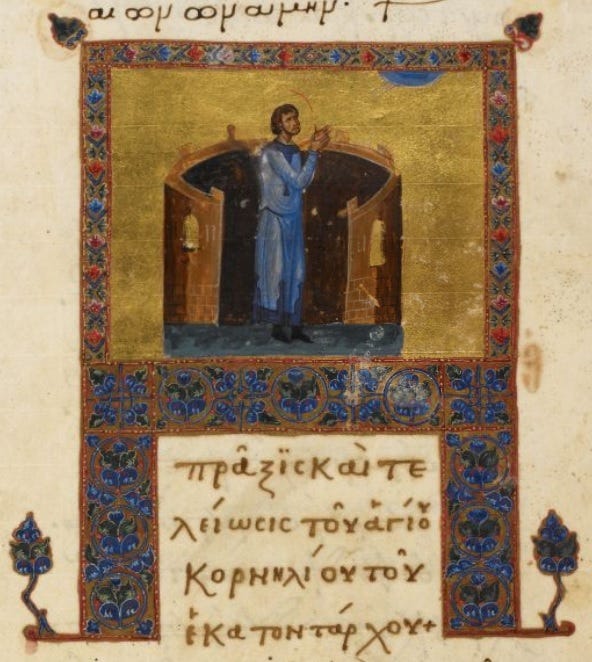

This framework also gives us a valuable perspective from which to consider later hagiographies in the Byzantine Lives of the Saints. Too often these have been dismissed or neglected as being the internal catechism for Orthodox Christians - indeed their original purpose - and a poor, lowbrow literary form of little interest to scholars. They are also understandably unpopular among pagan sympathisers and contemporary pagans alike, given their role in conversion and spiritual redirection.

However, more recent scholarship has revealed the multifaceted value of Christian panegyric hagiographies: (to clarify, here I am writing specifically of those found in Greek Orthodox Christianity as these are the ones whose conceptual framework I am exploring: some of this may also apply to local saints as well as those in the Catholic canon who are not recognised by the Eastern Orthodox Church, but they are outside my scope here).

Christian hagiographies: A rich seam

Regarding Orthodox hagiographies then: firstly, their style and genre derives directly from the late antique holy-man biography. Not only does this place them in a literary tradition of interest for its own sake; it is a valuable record of the evolution of this tradition. This became a literary genre in its own right, taken very seriously by Byzantine scholars, as seen especially through the work of Symeon Metaphrastes, who undertook to rewrite dozens of hagiographies in a “high” literary style extolled by Michael Psellos in his eulogy for Metaphrastes.12

Secondly, the holy-man biography provides a template and set of mythic tropes that changed little if at all over the centuries: this became an important vehicle for pagan vestiges even when the figures and valorised virtues changed. In many such hagiographies we find only the barest of Christian veneers, with the main thrust of the storytelling and motifs maintaining a recognisable pagan core. Vernacular biographies not associated with Christianity, such as the Alexander Romance and the Ballad of Digenes Akritas reflect these elements even more strongly.

Thirdly, as they were written and rewritten numerous times as new saints were beatified over the centuries, they also reflect how the vernacular oral, the “high” literary, and the visual iconographic traditions informed each other in a seemingly endless feedback loop. There are multiple examples of oral folk storytelling informing formal church-sanctioned hagiographies and vice versa; most importantly, where folk tradition and practice was especially persistent, we see it eventually reflected in the official Lives, rather than censored. There are also examples of overtly pagan practices deriving from this interplay between folk and Church tradition. We will see examples of all these elements in future instalments.13

Beyond the profiles of known scriptural figures, subgenres14 of this literary form include hagiographies of the warrior saints, of ascetics, mystics, saints pertaining to specific maladies, to women’s mysteries, and sometimes, even pagan figures such as Plato and Aristotle, reframed as precursors heralding the birth of Christ and salvific gift of Christian faith.

This is just one of the many elements of Orthodoxy which provides the richest of seams for exploring evolutions and persistencies bridging the late antique pagan world with the Byzantine theocracy - which was far from the period of stagnation and stasis that has often been imagined in the past.

See this article on St Barbara as an avatar of Hekate for a few examples of the abοve; more will be forthcoming in future instalments!

Hekate's Honey Cakes and a Poxy Saint

It is freely acknowledged by the Orthodox Church that in the early Christian period, deliberate efforts were made to replace Pagan deities with figures from the new religion that resembled them, while retaining elements of the previous ritual. Their integration into folk religion and fusion with folk practice was acceptable as long as it served to foreground the new religion. This was commonly done by the Greeks; Hesiod’s Theogony is a masterclass in fusing the older chthonic beliefs and deities with the ‘new’ Olympian ones; it is seen again in Roman times where similarities served as a bridge for Roman hellenisation, in Hellenistic Alexandria, and across the Greek colonies.

Matthias dall’Asta, Philosoph, Magier, Scharlatan und Antichrist: Zur Rezeption von Philostratus’ Vita Apollonii in der Renaissance, Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 2008; cf. Nikoletta Kanavou, Philostratos’ Life of Apollonios of Tyana and Its Literary Context, C.H.Beck, 2018, 4.

M. Dzielska, “On the memoirs of Damis,” Apollonius of Tyana in legend and history, Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 83-85, 186-192.

Jones, C. P. “An Epigram on Apollonius of Tyana.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 100, 1980, pp. 190–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/630745.

Gerard Boter, “The Title of Philostratus’ Life of Apollonius of Tyana,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 135 (2015) 1-7 (1,6).

Jones, C. P. “An Epigram on Apollonius of Tyana.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 100, 1980, pp. 190–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/630745.

Anonymous, The Life and Miracles of St Thekla, in Jones, “Apollonius,” Online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Johnson_ed.Greek_Literature_in_Late_Antiquity.2006

Speyer, W. ‘Zum Bild des Apollonios von Tyana bei Heiden und Christen’, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 17 (1974): 47–63 (5); Jones, “Apollonius,” Online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Johnson_ed.Greek_Literature_in_Late_Antiquity.2006

Photios, Myriobivlon 44; J.H. Freese trans. Online: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/photius_03bibliotheca.htm. Photios also decries the descriptions of Indian wonderworkers as a waste of time. Curiously, Photios states that Philostratos “denies that [Apollonios] was a wonder-worker, if he performed some of the wonders that are commonly attributed to him, they were the result of his philosophy and the purity of his life. On the contrary, he was the enemy of magicians and sorcerers and certainly no devotee of magic.” Either Photios’ reading is extremely objective, or perhaps scribal interventions are at play.

See :

Patricia Cox, Biography in late antiquity: A quest for the holy man, University of California Press, 1983, xv.

Cox, Holy Man, xi.

Elizabeth A Fisher, Michael Psellos: On Symeon the Metaphrast and On the Miracle at Blachernae: Annotated Translations with Introductions, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_FisherEA.Michael_Psellos_on_Symeon_the_Metaphrast.2014.

A key source for some of these points as well as fascinating explorations of the qualities of Orthodox hagiographies in the context of wider Byzantine Literature is Stratis Papaioannou ed., The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Literature, OUP 2021; also Christopher Walter, The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition, Routledge 2013 [Ashgate, 2006].

Hinterberger, Martin. 2014. “Byzantine Hagiography and its Literary Genres. Some Critical Observations.” Pages 25–60 in volume 2 of The Ashgate Research Companion to Byzantine Hagiography. Edited by Stephanos Efthmiadis. 2 vols. London and New York: Routledge.