Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

This is the fourth piece in my ongoing series exploring how the magic and ritual of Byzantium live on in modern Greek life. Each installment tackles a different angle. This one examines icons as living agents in Greek folk magic.

The first article looked at sensory theology more generally, with a close examination of Neoplatonic theurgy in its Orthodox manifestation. The second outlined the textual and material evidence for icon theology, including an overview of the Iconoclasm. This current two-part installment examines the practical functions of sacred icons.

In Part One we traced how the metaphysics of image animation shifted from pagan theurgy into the Orthodox theological grammar of icons, chrism, and grace, where the image remained a site of power and presence.

Here in Part Two, we follow these threads into lived ritual - Graeco-Byzantine and Modern Greek. Here, sacred images are kissed, carried, buried in fields, invoked in illness, and loved. The aim is not to romanticise “survivals,” but to show how the sacred image retained its function, even as names and theological scaffolding changed.

Each article stands alone, exploring a different facet of the topic, but together they form a broader study of the transition from pagan theurgy to icon animation across textual, material, and intangible culture.

A generous preview is open to all readers. If you’d like to explore the deeper layers of this story—and support the research that makes this work possible—I’d love to welcome you as a subscriber.

Subscribers also receive rare translations, deeper explorations of material culture, and future essays connecting Greek ritual to broader Mediterranean traditions.

Your support makes it possible for me to keep researching, writing, and sharing these hidden layers of Greek history and ritual. Thank you for being part of this journey.

Folk Ritual and Magicoreligious Practices

Far from being marginal superstitions or footnotes to Orthodoxy, as they have been treated in the past, they represent the sensory, social, and metaphysical heart of Greek religious life—then and now.

This should not be understood as merely passive survival, but active, intellectual mediation: “Byzantium was a fascinating laboratory for cultural and intellectual fusion, reception, combination, and reinvention,” actively selecting and reshaping ancient material for new theological and cultural contexts.1

Clerical complicity was/is not uncommon. Parish priests in both Byzantine and Ottoman-era contexts were/are known to bless objects clearly intended for magical use or to offer prayers that are overtly protective charms rather than formal liturgical petitions. These are among many examples demonstrating the significant divergence between official theology and everyday pastoral practice, particularly when navigating the demands of popular religiosity.2 This reflects what has been identified as a defining tension in Byzantine intellectual life, where Orthodox authorities “managed to ruthlessly suppress the transmission of heretical texts,” yet tolerated or negotiated practices that did not overtly threaten ecclesiastical authority. Nonetheless, more texts have reached us than this statement suggests.3

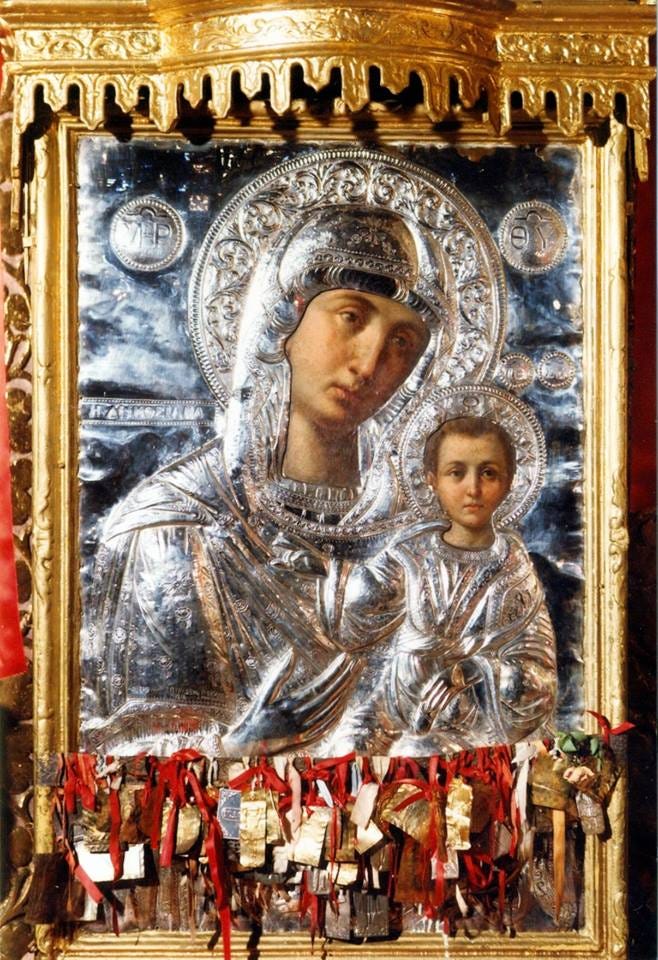

From village processions to miracle-working icons, from magical amulets placed beneath the Panagia to ritual consecration with chrism still prepared at Fanari today, the sacred image lives on—speaking the same grammar, in the same language, with added accretions, but few, if any losses.

While icons were theologically justified as visual aids to devotion and carriers of divine grace, in practice they frequently became the focus of popular ritual activity that preserved magical or apotropaic features rooted in pre-Christian antiquity. These practices reflect a continuity of function between late antique statuary and Christian iconography, wherein sacred images operated not merely as devotional tools but as active agents of divine power.

Icons and Communal Protection

The Life of St. Theodore of Sykeon (7th century) documents villagers placing the saint’s icon at the village boundaries to avert plague. In such practices, the icon is physically transported, installed, and accompanied by processional chants and invocations—a structure strongly reminiscent of ancient apotropaic rituals involving cult statues and boundary protection.4

Similarly, in the Life of St. Mary the Younger (10th century), an icon of the Theotokos is described as weeping during a communal crisis, a sign interpreted as a divine expression of grief and warning.5

In some locales, icons were said to glow at night or emit perfume, signs interpreted by locals as divine signals. These perceptions persisted through the Ottoman period, when icons were often the only perceived protectors left to a politically disenfranchised Orthodox laity. Some communities buried icons in fields to protect crops—blending apotropaic folk ritual with Christian devotional objecthood.6

Theatrical Liturgy: Manipulating the Senses in Sacred Space

This impression of ‘glowing’ is not necessarily a sensory experience brought on by intense faith: in the church context, it is by design, much like the auditory effects intentionally built into the architecture. Icons were deliberately crafted to engage the senses through the shifting interplay of candlelight and incense, to create what has been called poikilia - a “polymorphous presence” contributing to a physical experience of animation among the worshippers.7 This strategy reflected a distinctly Byzantine theory of art, which viewed sacred images as “constituted by a manifold of qualities such as color, texture, surface, and luminosity,” aiming to generate “a dynamic presence capable of engaging the senses of the beholder”8

This reflects far older practices in which the ancient priesthood would deliberately engage, disorganise, and rearrange the sensory impact of rituals - most notably at the necromanteia and chthonic shrines, where visual and spatial techniques were consciously employed to manipulate perception.

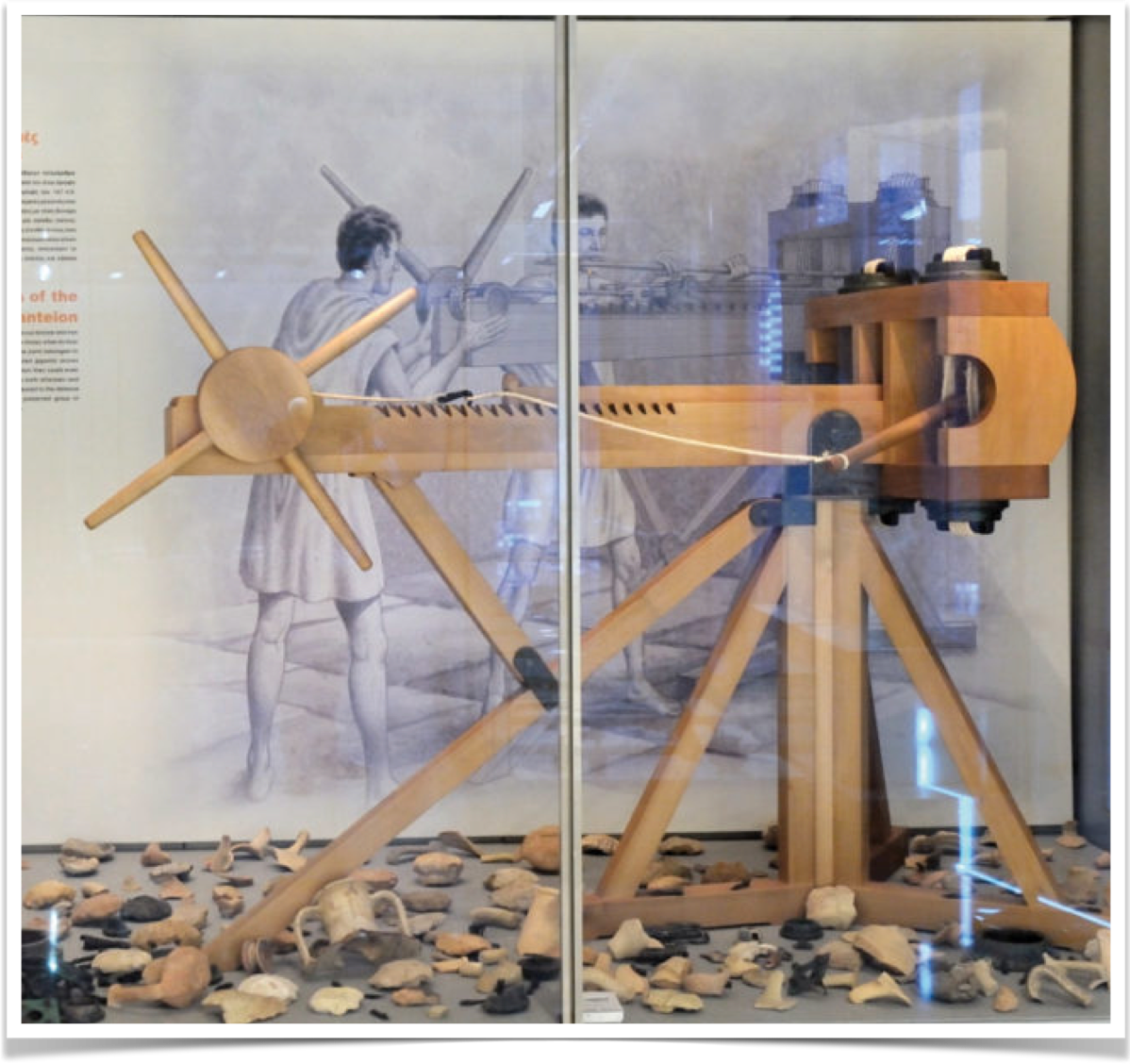

At the Necromanteion of Acheron, visitors seeking communion with the dead were subjected to deliberate sensory disorientation. Following long prayers and fasting, they were led through a labyrinthine sequence of dark corridors, subterranean chambers, and echoing halls. Archaeological analysis confirms the presence of mechanical devices including pulleys, trapdoors, and suspended effigies, to simulate apparitions of the dead. The descent into the oracular space mimicked a katabasis, choreographed to provoke awe and suggestibility.9 Similar sensory manipulations through architecture, controlled light and acoustics, augmented by the experience of fasting, bathing, and ritual chants are attested at the Asklepieion at Epidavros and other healing sanctuaries of antiquity. It is these practices that the Orthodox church inherited.10

Far from mere trickery, these mechanisms of presence were part of a broader liturgical dramaturgy (and keen understanding of psychology), in a cultivated grammar of sensory encounter that later traditions, including Christianity, inherited and repurposed. We may no longer use pulleys and cranes, but in both cases, sensory manipulation and sacred drama is used for physical and spiritual renewal, raising questions as to whether we cannot be talking about a very powerful material continuity.

Healing and Tactile Engagement

The theological basis for treating icons as animate agents lay in Orthodox doctrines of hypostasis and presence, as I have discussed in previous articles. Byzantine theology regarded the icon not merely as a representation but as “a hypostatic image,” participating in the reality of its prototype and thus capable of transmitting divine energy.11

Icons were (and are) regularly employed in healing rituals. Faithful supplicants kiss, touch, or anoint icons; cloths or cotton wool are rubbed against miracle-working images and then applied to afflicted bodies. Such tactile practices reflect a persistent belief in the transmission of dynamis (divine power) through the image’s material surface, mirroring ancient practices at temples of Asklepios and Isis.12

Icons were (and are) frequently brought into homes or sickrooms, fulfilling both sacramental and magical roles. Their effectiveness was believed to depend not only on faith but also on proximity, gesture, and ritual repetition—all traits preserved from earlier ritual models.13

That concludes the free portion of this essay.

What follows explores the deeper theological and ethnographic dimensions—why magic never vanished from Orthodox practice, how sacred images retained their power, what this means for understanding modern Greek religious life, and concerns about problematic scholarship and why this material is not more widely known.

Subscribers will also receive the upcoming rare first English translation of a remarkable 1925 Greek study documenting magical practices in folk Orthodoxy.

If you’ve found this valuable so far, I’d be delighted if you considered subscribing to read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thyrathen: Greek Magic, Myth, and Folklore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.