How Pagan Magic Shaped Christian Icons 1/2

The Statues Never Stopped Speaking: Sacred Image Traditions from Late Paganism to Byzantium

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

In earlier installments, I explored the Neoplatonic framework behind Orthodox ritual, and how icons function as vessels of divine presence. I explained how Orthodox ritual engages all five senses in a Neoplatonic frame, and how icons are not mere paintings but sacramental inscriptions. Today’s offering explores continuity in practice.

If function, mechanics of material invocation, ritual, and their sociocultural role are conceived as a grammar, and their material expression as a vocabulary, then irrespective of adaptations and accretions to the underlying theology, there is a clear throughline within their evolution.

Below, I lay out the ritual grammar that predates Orthodoxy but survives within it. From miraculously appearing statues to the solar cult of Constantine and the lunar elevation of Helena, what emerges is a continuous metaphysics of image animation. And while there are undoubtedly modifications - as there were between pagan generations, there is a throughline of practice that cannot be ignored.

Far from rejecting them, Orthodox theology repurposed these practices, transforming telestikē into consecration rites and adopting the language of divine energy and presence, sanctified now by chrism and liturgy. Perhaps the greatest change of all, however, was the shift from elite back to communal public practice. Here I outline evidence on how ancient image cults became the theological and ritual foundation for Byzantine icon veneration.

This is Part One of a two-part study; Part Two will examine how these continuities endured not only in theology but in popular ritual and lived devotion.

I’m currently preparing to travel to Vilnius for the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism, where I’ve been invited to speak at the Orthodox–Esotericism Working Group on related themes. My Notes will be quieter while I’m away, but the usual Sunday publishing schedule will continue uninterrupted. Part Two appears next week, and the week after that, subscribers will receive a first English translation of a remarkable 1925 Greek folklore study on Byzantine folk magic, defixiones, curses and other magical practices along with their full evidence base—material that speaks directly to these broader questions.

On Ritual Grammar

The theological language of Orthodox icons is not merely doctrinal or aesthetic. It draws from a much older ritual grammar shaped by Neoplatonic metaphysics and late antique syncretic magical practices. By the 4th to 6th centuries, long-standing practices of statue animation began its transition to parallel practices of icon veneration and statue divination. Many statues once ensouled through ritual were relocated to public or semi-sacred spaces and continued to be used—sometimes openly, sometimes covertly—for ritual and magical purposes.

For those naturally wary about continuity claims, I have written elsewhere about the distinctions between continuity, survival, and persistence. So do bear with me: in what follows, supported by textual evidence as well as the scholarly consensus, I attempt to classify each case accordingly—grounded in both textual evidence and scholarly consensus. At the end of Part Two, I’ll turn directly to the academic distortions that have allowed these dynamics to remain obscured for so long.

Telestikē: The Sacred Craft of Theurgy

Though many of my readers do not need this introduction, it is a necessary point of departure and may be valuable to non-specialists.

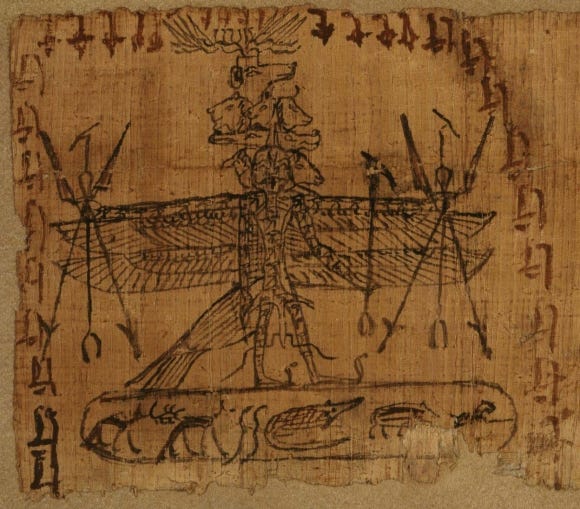

Drawing on Egyptian ritual practices and evolving through syncretism, Greek statue animation, known as telestikē, became a refined theurgic art in the Hellenistic era. A process understood to instill divine presence into statues and images through ritual consecration, it was foundational to late Neoplatonist theology, elaborated in the writings of Iamblichos and Proklos.

The Greco-Egyptian syncretism that shaped Neoplatonic theurgy elevated these rituals into hieratic philosophy. In On the Mysteries, Iamblichos explains how divine presence could dwell materially within cult images through sacred symbols and divine invocation.

Proklos further details in On the Hieratic Art that an image becomes a vessel for divine presence through symbolic actions: inscribing sacred names, choosing astrologically opportune times, and performing appropriate rites of anointment, thereby creating a receptacle for divine energy.1 These views underpinned a complex tradition of ritual image consecration extending from Egyptian and Hermetic practices into late antique Neoplatonism.

The Greek Magical Papyri (PGM), a set of Greco-Egyptian ritual texts compiled between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE, includes numerous examples of image-based ritual, such as invocations of deities through figurines, consecration of statues with oils, and magical ensoulment through names and rites.2

This blend of magic and metaphysics lies at the heart of Byzantine icon theology and I do not think we can consider it “just” a persistence, for reasons I will address below. Many scholars have made this observation, but it remains marginalised for reasons to be discussed in Part Two of this article.

These telestic principles—ritual, symbolism, divine presence in matter—did not vanish with the end of paganism, nor were they confined to abstract theology. Instead, they were modified and strategically repurposed—first by emperors, then by bishops, and eventually by popular devotion.

One of the clearest bridges between late antique image-cult and Orthodox icon theology lies in the evolving function of the palladion: a sacred image whose power was not artistic but ontological, protective by nature and divine by origin.

From the Palladion to Acheiropoieita icons

One of the most striking examples of pagan symbolism being reinterpreted within a Christian context is the concept of the palladion—a sacred image believed to guarantee the protection of a city or realm. In its pagan origin, the most famous Palladion [Palladium] was the xoanon of Pallas Athena in Troy, believed to have fallen from the heavens in response to the pleas of Ilus, founder of Troy.3 Her celestial origin - as opposed to human craftsmanship, is key to icon theology.

The legendary statue became central to Roman identity. Constantine’s founding of Constantinople intensified this symbolism. According to 6th-century chronicler John Malalas, Constantine stealthily relocated the Palladion from Rome and interred it beneath the Forum’s porphyry column (the Column of Constantine - on which more below), thereby reassigning the city’s divine protection from Rome to “New Rome,” sacramentally embedding the city’s protectress at its heart. 4

The Palladion legend was swiftly woven into Constantinopolitan topography. Its placement beneath the column transformed it into a hidden relic—a palimpsest combining the Trojan mythos with imperial cosmology in a deliberate act signalling continuity.5 The subterranean symbolism also explained the persistence of oracular and thaumaturgic beliefs.

In a seamless evolution of sacred image beliefs, the ancient concept of a divine protector embodied in an image was transmuted into Byzantine icon veneration. The Tyche of Constantinople; the city’s fortune, was personified on medallions and temple fronts wearing a turreted crown. An embodiment of pagan protective images, adapted from Cybele’s iconography by Constantine, she remained despite the growing Christianised mythopoeia.

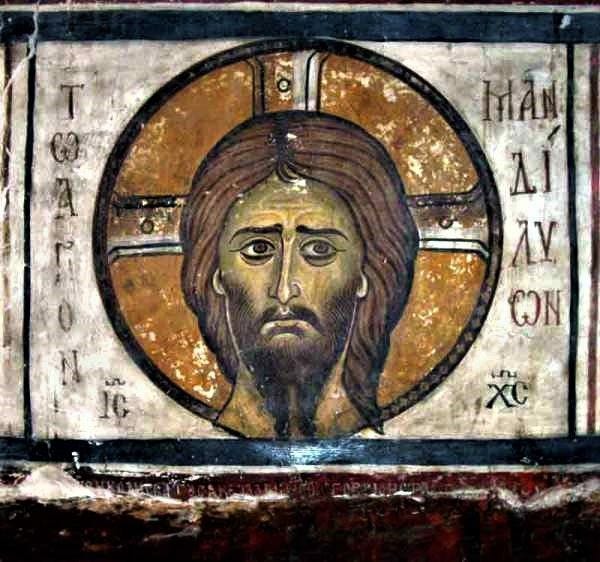

Concurrently, acheiropoieita—or “icons not made by human hands” (miraculously found, not made)—began to emerge within Christian practice. These miraculous icons fulfilled a role analogous to the Palladion as conduits of divine presence whose legitimacy lay in their apotropaic efficacy and sacral provenance.6 Once enshrined, they became city guardians—much like the Palladion before them.

By the late sixth century, Byzantium had come to venerate Christian palladia, notably images of Christ or the Virgin believed to carry protective power during wars. These were routinely paraded on the city walls during sieges. The Mandylion or Image of Edessa, reputedly miraculously imprinted with Christ’s face, first appears as a protective image in Evagrius Scholasticus’ account of 593, credited with averting a Sassanid siege of Edessa.7 Alongside the Mandylion, the icon of Kamoulianà [Camuliana, Cappadocia]—another acheiropoieton—was carried in military processions, becoming a talismanic artifact capable of influencing imperial fortunes in key battles .8

Byzantine devotion to icons like the Odegētria and the Tyche cult fused civic protection, divine presence, and ritual practice into a cohesive iconological worldview. The transition from pagan statue cult to Christian icon palladia reveals less break and more strategic adaptation—a theological and cultural transformation carried out by bishops and emperors for their own purposes, but embraced and further adapted by the wider populace.

These early Christian palladia closely mirror their pagan predecessors in function, but crucially, also in origin. The acheiropoieita (not made by hands) nature denotes their creation through divine agency, an argument that was later used to justify the use of sacred images during the iconoclasm (on which more here).

Their emergence signals the blending of apotropaic traditions in Byzantine culture with a novel theology of sacred imagery: an evolution, not a break. 9

This reflects a twofold significance: the Christian palladion retained the pagan function—a safeguard of earthly powers—but doubles down on its nature as evidence of divine incarnation and protection. Not simply venerated, these objects were celebrated for being directly created by divine force, rather than crafted by artists. This both preserved the mythic gravity of the Palladion and transformed it into a visual affirmation of Christian doctrine.

By the time the Mandylion reached Constantinople in 944 amidst great ceremony, it had already been suffused with centuries of layered meaning. Far more than a sign of imperial favour or divine protection, it was the Christian palladium par excellence—an acheiropoieton that symbolised and embodied incarnation itself in a seamless evolution of icon theology whose continuity was both acknowledged and officially sanctified, not only by the Church, but by the imperial cult.10

The Imperial Cult: Constantine-Helios and Helena-Selene

In the early visual and ideological landscape of Constantinople, Emperor Constantine I was explicitly portrayed in the guise of Helios, the unconquered sun. His mother, Helena, was correspondingly depicted as Selene, the moon goddess. This solar-lunar dyad invoked late Roman cosmological imagery and lent metaphysical legitimacy to the Constantinian dynasty. It also aligned the imperial family with celestial order and divine sanction.

Constantine’s Helios-imagery is well documented. At the centre of the Forum of Constantine stood the monumental Colossus of Constantine—a colossal statue of the emperor in a radiate crown, positioned atop a porphyry column (the Column of Constantine). Aligning Constantine with Sol Invictus, to whom he was known to be devoted before his deathbed conversion to Christianity, the buried fragment of the Palladion lent further mythic resonance to the emperor’s divine status.11 His mother Helena was depicted as Selene-Aphrodite. This statue, still extant, reflects the pagan imperial tradition of associating dynastic figures with cosmic forces.12

These images predate the hagiographic transformation of Helena into the pious discoverer of the True Cross and demonstrate the extent to which imperial self-representation was deeply steeped in pre-Christian religious and cosmological frameworks. Rather than evidence of personal piety, this iconography positioned Constantine and his family within a divine cosmic order familiar to Roman religious imagination.

These representations reflect the attempt to link the Constantinian dynasty with celestial and divine legitimisation, even before the full articulation of Nicene orthodoxy. Ιt has been suggested that Helen’s inclusion was intended to rehabilitate her low-born status and stave off ambivalence regarding Constantine’s own legitimacy. This monumental pairing with Constantine elevated her politically and spiritually, especially in public visual culture, making them one of the most beloved pairs of saints in Greek folk culture, about which more in Part Two.

This layering of Christian and late pagan motifs reflects the ideological fluidity of the early 4th century imperial milieu. More importantly, the shift from Helios-Selene to twin Christian saints (a mother-son dyad rather than a divine couple, transformed through the ‘discovery’ of the most sacred Christian relic of the True Cross— ie, material culture), precisely tracks how this transition between pagan cultic symbolism to Christian sacred imagery occurred. This clearly illustrates the use of divine personification as a mode of asserting spiritual authority - one of the clearest reflections of the Greek theological idiom recognisable long before Christianity.

The divine power once embodied in Helios and Selene was reconfigured into the iconography of Christ Pantocrator and the Theotokos, echoed in the more familiar double icon of St Constantine and the rehabilitated Helena.

From Cult Statues to Icons

Thus, while Christian theology rejected the polytheistic framework in name, it preserved the metaphysical assumption that the divine could be mediated through material objects, alongside the notion of divine ascent of mortals, laying the groundwork for icon theology.

With imperial support for Christianity, the practices of statue animation transitioned into a combination of icon veneration and statue divination, with temple statues relocated to public locations and used for magicoreligious purposes, both overtly and covertly. Their reinterpretation (“re-semanticisation”)13 enabled their persistent visual dominance in public life, with an oddly powerful role.

In the 6th century, John Malalas describes the statue of Apollo at Daphne near Antioch being used for clandestine divination.14 Similarly, the 7th-century Life of St. Theodore of Sykeon recounts villagers invoking icons for magical protection, placing them at village boundaries while chanting incantations—practices almost identical to older apotropaic rituals conducted with statues,15 which persist to this day.

Further key examples are found in the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai (8th-9th century), a Byzantine text cataloguing many statues in Constantinople and revealing the persistence of pagan statuary and their miraculous powers attributed by the public imagination even centuries after official Christianisation. It tells of a statue of Athena that gave oracles until it was sealed by Christian prayers. Another entry refers to the apotropaic nature of the statue of Constantine, whose outstretched hand turned toward danger.

The remainder of this piece traces how ancient theurgy was reconfigured within Orthodox consecration rites, how chrism bridges matter and grace, and how these logics carried from imperial theology into living popular ritual.

Click below to continue—or consider upgrading for access to full footnotes, archival translations, and the extended second installment, which will also include a subscriber-only section.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thyrathen: Greek Magic, Myth, and Folklore to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.