On the secret meanings of urinating baboons

And why this translation was needed: Excerpts from my new translation of the Hieroglyphica along with juicy footnotes.

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

I hope readers will forgive this temporary digression into all things Hieroglyphica as my excitement reaches a fever pitch with publication imminent!

I am so grateful for the warm response to these announcements thus far; I am also preparing a number of other surprises for my readers (thank you all so much!!) that will bring us back to the main themes of this journal/blog/newsletter!

Today’s offering is a final excerpt from my forthcoming Hieroglyphica: a section from the preface telling readers exactly what they’re getting, followed by a sample of the manuscript itself, plus translation and notes.

Pre-order is now live, the book is available here.

From the Preface, p. xx

Why a New Translation?

[…]

There are only two English translations of the Hieroglyphica in circulation: The first by Alexander Turner Cory in 1840 (available online and in print on demand facsimile), the second and most widely accessible by George Boas in 1950 (reprinted 1993).1

The first is a product of its time, and despite a sympathetic treatment, it suffers from the poetic affectations plaguing many Victorian translations. It also features inaccuracies in the transcription of the Greek, interpretation and translation, as indicated in the notes to the present translation.

Boas’ 1950 edition is the most widely used in recent decades. This is a reader-friendly freestyle, indirect translation, not from the Greek, but from a neo-Latin manuscript,2 with a speculative and inaccurate introduction that reflects the time of writing, and is a product of Boas’ stated approach, as “neither a Hellenist nor an Egyptologist, [but] a historian of ideas and of taste',” preparing the translation for “the wants of the iconologist… not for the student of either Greek literature or Egyptian culture.”3

This has strongly influenced his perspectives and translation choices, whilst the limitations set by disciplinary boundaries of his day are clearly visible.

These are not manners of pedantry or scholarly one-upmanship:

Though the Boas edition contains interesting insights in the Introduction, it is not fit for purpose due to the indirect translation. The arbitrary subjectivity of approach and the dated perspectives on Egyptology and the manuscript itself are equally problematic.

The serious scholar must resort either to the definitive critical edition by Francesco Sbordone (1940), which despite its age remains the most detailed of the editions, but it exists only in Italian and shows signs of disciplinary bias4 in the approach to the manuscript. The 1943 and 1947 French translation and addenda by van de Walle and Vergote are the next best option but rest heavily on Sbordone.5

Both are philological in approach, and while this leaves the commentary open to some bias, the analysis and referential framework is valuable. I cannot opine on the quality of translations into other languages, though I note that in the Zàrate Spanish edition, the editor has apparently arbitrarily rearranged the sequence of the entries.6

Recent scholarship has called for a fresh English translation along with a contextualisation that takes into account the considerable interdisciplinary body of literature that has evolved in recent years.

Some of the most intensive recent work on the Hieroglyphica has been done by diverse scholars: papyrologist Jean-Luc Fournet and a team of experts convened at the Collège de France, emblem scholar Pedro Germano Leal, and specialist in ancient philosophy, Mark Wildish.

Leal developed a detailed theory according to which he believes the Hieroglyphica to have originally been written in Coptic, and is attempting to identify and reconstruct what he terms “the indigenous nature of the Hieroglyphica.”7 Though I disagree with some of his conclusions, I believe that his completed projects will provide valuable insights.

Wildish has analysed the text according to Neoplatonist metaphysical philosophy, and his study is invaluable to the present commentary. Fournet has written several valuable relevant articles and convened a 2018 colloquium at the Collège de France under the Chair of Late Antique Written Culture and Byzantine Papyrology: Studia Papyrologica et Aegyptiaca Parisina (StudPAP).

This was devoted to situating the Hieroglyphica in “modern Europe” through an in-depth look at its “history, fiction, and reappropriation.” The published volume from the colloquium features fifteen cross-disciplinary studies encompassing approaches from Egyptology, Late Antique Literature, Art History, Modern Literature, and Reception Studies. In his introduction, Fournet emphasises the need for:

…[a new] systematic annotated edition of the Hieroglyphica, combining a close analysis of the text and its manuscript tradition, the most recent contributions of Egyptology, and a study of the Greco-Roman traditions at work behind Horapollo’s commentaries, while emphasising the decisive impact that this work has had on the artistic and emblematic domain in the modern era.8

The colloquium papers break new ground but also make some omissions and draw erroneous conclusions. These are addressed in this commentary.

[…]

Preface, p. xxiv

This Translation and Commentary

This translation is intended to act as an entry-point both for the general reader, and scholars from a range of Humanities disciplines. I am aware of the risks of trying to please diverse audiences, but my priorities are to provide as rich a context as possible, alongside a clean, accurate, usable translation that avoids the problems inherent in both Cory and Boas.

In preparing this commentary I made three new discoveries that break fresh ground in our understanding of the Hieroglyphica. I must emphasise that these are in a preliminary form; they require further research not permitted by the scope of the present volume. However, I have been able to identify strong evidence for the following that add significant new dimensions to our understanding and call for the manuscript’s urgent reevaluation:

The Hieroglyphica is a product of oral transmission, probably written down by a student of Horapollon.

It clearly reflects the late antique Alexandrian amalgamation of Egyptian religion and Greek Neoplatonism, infused with Hermetic influences.

Late antique alchemical hermeneutics are reflected within some of the entries.

In addition, I list two apparently undiscovered manuscripts from Greek libraries. The above findings are not the result of anachronistic errors of interpretation: each has been pinned down in the contemporary literature alongside rigorous recent scholarship.

Furthermore, I have conclusively refuted suggestions of Byzantine pseudepigraphy from the recent literature, highlighted previous mistranslations of key elements, and provided guidelines for further research. All these are presented with evidence below.

[…]

Preface, p. xxvi

How to use this book

The general reader may wish to skip the more technical discussion in the Introduction and Part 6, and dive directly into the mysteries of the manuscript in Part 1, or the Alexandrian world covered from Part 2 onward.

Notes on the translation itself tie it into the commentary, but have been limited mainly to Book One of the Hieroglyphica due to the doubtful authorship of Book Two.

This is intended as a gateway to a long overdue holistic reevaluation of this manuscript, while the general reader will come away with a fuller understanding of this complex and enthralling period of history and the place of hieroglyphic interpretation within it.

With these points in mind, this commentary is structured as follows:

The Introduction summarises our current knowledge on the Hieroglyphica, predominant theories regarding its authorship and composition, points on reception studies, and questions of decolonisation in studying Hellenic and Byzantine material and its reception.

Part 1 engages with the authenticity of the manuscript and the identity of the author.

Part 2 presents a survey of the late antique world of fifth century Alexandria, where we seek the historical Horapollon through the testimonies of his students, exploring the turbulent events leading to the last stand of the Schools of Alexandria and Athens against a still-fragmented Christianity, and the fate of pagan thought.

In Part 3 we explore the mythic and intellectual context to discover the strategies and approaches to hieratic philosophy and magical practice in the face of ever-stricter Christian dogma, tracing the role of hieroglyphs and their interpretation through Egyptian and Greek thought.

This leads us, in Part 4, to an investigation of language and metaphysics in the context of pagan philosophy as well as early Christianity. Here we examine the potential for a Hermetic and alchemical hermeneutic stream adjoining Neoplatonist input into part of the manuscript.

Part 5 provides a summary of the discovery of the Hieroglyphica in the Renaissance, its multiple misinterpretations, and the explosive creativity they ignited. This has been exhaustively covered by other scholars, therefore I have kept it brief.

Part 6 presents translation-related technicalities. Then we encounter the manuscript itself, in the original Greek and the new translation. The Appendix contains further information mainly of value to scholars seeking to continue work on this mysterious manuscript.

[…]

Book One of the Hieroglyphica, p. 301

Book One

θ’. Πῶς γάμον

Γάμον δὲ δηλοῦντες, δύο κορώνας πάλιν ζωγραφοῦσι του λεχθέντος χάριν.

x. How Marriage

To signify marriage, they again draw two crows for the reasons already stated.9

ι’. Πῶς μονογενές

Μονογενὲς δὲ δηλοῦντες, ἢ γένεσιν, ἢ πατέρα, ἢ κόσμον, ἢ ἄνδρα, κάνθαρον ζωγραφοῦσι. μονογενὲς μὲν ὅτι αὐτογενὲς ἐστι τὸ ζῷον, ὑπὸ θηλείας μὴ κυοφορούμενον. μόνη γὰρ γένεσις αὐτοῦ τοιαύτη ἐστὶν· ἐπειδὰν ὁ ἄρσην βούληται παιδοποιήσασθαι, βοὸς ἀφόδευμα λαβῶν, πλάσσει σφαιροειδὲς παραπλήσιον τῷ κόσμῳ σχῆμα, ὅ ἐκ τῶν ὀπισθίων μερῶν κυλίσας ἀπὸ ἀνατολῆς εἰς δύσιν, αὐτὸς πρὸς ἀνατολὴν βλέπει, ἰνα ἀποδῷ τὸ τοῦ κόσμου σχῆμα· (αὐτὸς γὰρ ἀπὸ τοῦ ἀπηλιώτου εἰς λίβα φέρεται, ό δὲ τῶν ἀστέρων δρόμος ἀπὸ λιβὸς εἰς ἀπηλιώτην). ταύτην οὗν τὴν σφαῖραν κατορύξας, εἰς γῆν κατατίθεται ἐπὶ ἡμέρας εἰκοσιοκτώ, ἐν ὅσαις καὶ ἡ σελήνη ἡμέραις τὰ δώδεκα ζῴδια κυκλεύει, ὑφ΄ἣν ἀπομένον, ζωογονεῖται τὸ τῶνκανθάρων γένος· τῇ ἐνάτῃ δὲ καὶ εἰκοστῇ ἡμέρᾳ ἀνοίξας τὴν σφαῖραν, εἰς ὕδωρ βάλλει, (ταύτην γὰρ τὴν ἡμέραν νομίζει σύνοδον εἶναι σελήνης καὶ ἡλίου, ἔτι τε καὶ γένεσιν κόσμου), ᾖς ἀνοιγομένης ἐν τῷ ὕδατι, ζῷα ἐξέρχεται, τουτέστιν οἱ κάνθαροι. γένεσιν δὲ διά την προειρημένην αἰτίαν· πατέρα δέ, ὅτι ἐκ μόνου πατρὸς τὴν γένεσιν ἔχει ὁ κάνθαρος· κόσμον δέ, ἐπειδὴ κοσμοειδῆ τὴν γένεσιν ποιεῖται· ἄνδρα δέ, ἐπειδὴ θηλυκὸν γένος αὐτοῖς οὐ γίνεται. Εἰσὶ δὲ καὶ κανθάρων ἰδέαι τρεῖς. πρώτη μὲν αἰλουρόμορφος καὶ ἀκτινωτή, ἥνπερ καὶ ἡλίῳ ἀνέθεσαν διὰ τὸ σύμβολον· φασὶ γὰρ τὸν ἄρρενα αἴλουρον συμμεταβάλλειν τὰς κόρας τοῖς τοῦ ἡλίου δρόμοις· ὑπεκτείνονται μὲν γὰρ κατὰ πρωΐ πρός τἡν τοῦ θεοῦ ἀνατολήν, στρογγυλοειδεῖς δὲ γίνονται κατὰ τὸ μέσον τῆς ἡμέρας, ἀμαυρότεραι δὲ φαίνονται δύνειν μέλλοντος τοῦ ἡλίου, ὅθεν καὶ τὸ ἐν Ὴλιουπόλει ξόανον τοῦ θεοῦ αἰλουρόμορφον ὑπάρχει. ἔχει δὲ πᾶς κάνθαρος καὶ δακτύλους τριάκοντα διά την τριακονταήμερον τοῦ μηνός, ἐν αἶς ὁ ἥλιος ἀνατέλλων, τὸν ἑαυτοῦ ποιεῖται δρόμον. δευτέρα δὲ γενεά, ἡ δίκερως καὶ ταυροειδής, ἥτις καὶ τῇ σελήνῃ καθιερώθη, ἀφ’οὖ καὶ τὸν οὐράνιον ταῦρον ὕψωμα τῆς θεοῦ ταύτης λέγουσιν εἶναι παῖδες Αἰγυπτίων. τρίτη δὲ ἡ μονόκερως καὶ ἰβιόμορφος, ἢν Ἑρμῆ διαφέρειν ἐνόμισαν, καθὰ καὶ ἴβις τὸ ὄρνεον.

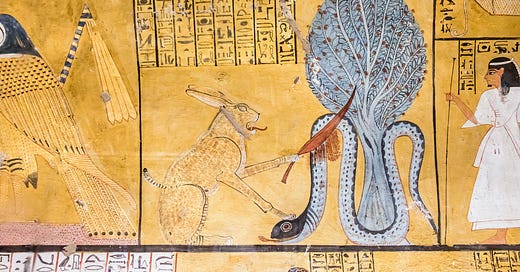

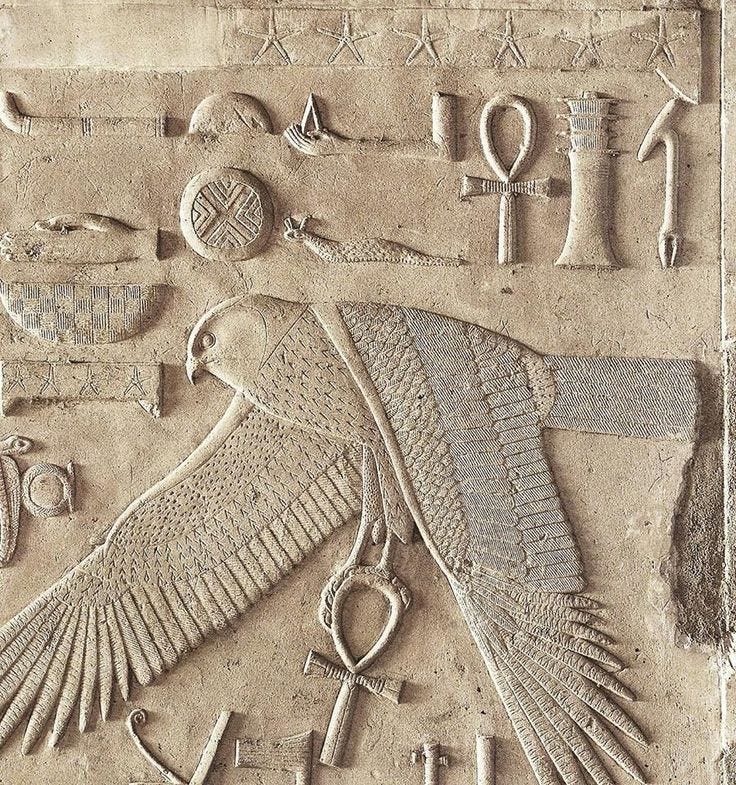

X. How Monogenés10

To signify an only child, or birth, or father, or the world, or a man, they draw a scarab beetle. It signifies a monogenés because the scarab is a self-generated animal, not gestated by a female. It is thus born alone, for this is the manner of its generation; when the male wishes to procreate, taking the dung of an ox, he shapes it into a spherical form resembling the world, he then uses his hind limbs to roll it from east to west, while he looks to the east, that he may impart to it the shape of the world, (for the world is borne from east to west; while the path of the stars is from west to east).11 Then, he digs and places the sphere in the earth for twenty eight days, as many days as the moon takes to circuit the signs of the zodiac; by remaining beneath the moon, the race of scarabs is given life. On the twenty ninth day, having opened the sphere, the scarab casts it into water, (for he believes this day to be the conjunction between sun and moon, and therefore of the birth of the world), as the sphere opens in the water, animals emerge, that is, the scarabs.12 It is thus birth for the aforesaid reasons. Also a father, since a scarab is only born from a father. The world, because its birth takes place through the form of the world.13 Man, because the female kind are not among them [scarabs].14 Additionally there are three kinds of scarab. The first has the form of a feline, with rays, and thus it is appointed a symbol of the sun;15 for they say that the male feline alters the shape of the pupils of his eyes according to the path of the sun; in the morning at the rising of the god they dilate; and at midday, they are round, and they appear darker as sunset approaches. Hence, in the Heliopolis there is a xoanon16 of the [sun-]god in the form of a feline.17 Every scarab also has thirty toes, for the thirty days of the month in which the sun rises and runs its course. The second type [of scarab] has two horns and resembles a bull, and is consecrated to the moon, whence the celestial bull is said to be an elevation of this goddess; so say the children of the Egyptians. The third type is single horned and resembles the ibis, as Hermes is thought to differ [from other gods].18

[…] Page 322

ιστ᾽. Πῶς ἰσημερίας δύο

Ἰσημερίας δύο πάλιν σημαίνοντες, κυνοκέφαλον καθήμενον ζωγραφοῦσι ζῷον. ἐν ταῖς δυσί γὰρ ἰσημερίαις τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ δωδεκάκις τῆς ἡμέρας καθ᾽ἑκάστην ὥραν οὐρεῖ, τὸ δὲ αὐτὸ καὶ ταῖς δυσί νυξὶ ποιεῖ· διόπερ οὐκ ἀλόγως ἐν τοῖς ὑδρολογίοις αὑτῶν Αἰγύπτιοι κυνοκέφαλον καθήμενον γλύφουσιν, ἐκ δὲ τοῦ μορίου αὑτῷ ὕδωρ ἐπιρρέον ποιοῦσιν, ἐπεί, ὥσπερ προεῖπον, τὰς τῆς ἰσημερίας δώδεκα σημαίνει ὤρας· ἰνα δὲ μὴ εὐρύτερον τὸ ὕδωρ ( ἐξ αὐτομάτου) κατασκευάσματος ὑπάρχῃ, δι᾽οὒ [τὸ ὕδωρ] εἰς τὸ ὡρολόγιον ἀποκρίνεται, μηδὲ πάλιν στενώτερον, (ἀμφοτέρων γὰρ χρεία, τὸ μὲν γὰρ εὐρύτερον, ταχέως ἐκφέρον τὸ ὕδωρ, οὐχ ὑγιῶς τὴν ἀναμέτρησιν τῆς ὤρας ἀποτελεῖ, τὸ δὲ στενώτερον, κατ᾽ ὀλίγον καὶ βραδέως ἀπολῦον τὸν κρουνόν), ἕως τῆς οὐρᾶς τρῦμα διείραντες , πρὸς τὸ ταύτης πάχος σίδηρον κατασκευάζουσι πρὸς τὴν προκειμένην χρείαν· τοῦτο δὲ αὐτοῖς ἀρέσκει ποιεῖν οὐκ ἄνευ λόγου τινός, ὡς οὐδὲ ἐπὶ τῶν ἄλλων. καὶ ὅτι ἐν ταῖς ἰσημερίαις μόνος τῶν ἄλλων ζῴων δωδεκάκις τῆς ἡμέρας κράζει καθ᾽ ἑκάστην ὤραν.

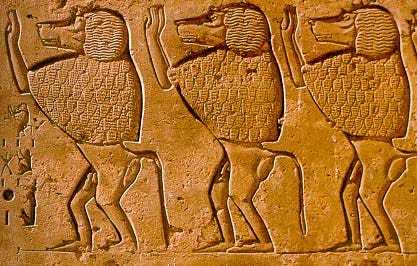

xvi. Ηow the two equinoxes

Again, to signify the two equinoxes, they draw a sitting kynokephalos. For at the two equinoxes of the year, it urinates twelve times in the day, once every hour, and it does the same during the two nights. Thus not without reason do the Egyptians carve a seated kynokephalos on their hydrologia [water clocks] and they cause the water to run from its member because, as previously said, the twelve hours of the equinox are thus signified. And lest the water run too broadly, an [automated] mechanism exists to regulate it, through which water runs through the clock, not with too narrow a stream, (for both are needed; the one that is wider, making the water flow fast, does not correctly measure the hour, and the one that is narrower, flows too slowly and only slightly); [hence] they loosen the tap by a hair’s breadth and they manufacture an iron plug for this purpose, according to the thickness of the stream [needed]. They do not do this without reason; more than in other cases, and during the equinoxes, this is the only animal that cries out twelve times a day, once every hour.19

[…] p. 333

κβ᾽. Πῶς Αἴγυπτον γράφουσιν

Αἴγυπτον δὲ γράφοντες, θυμιατήριον καιόμενον ζωγραφοῦσι, καὶ ἐπάνω καρδιὰν, δηλοῦντες ὅτι, ὡς ἡ τοῦ ζηλοτύπου καρδιὰ διὰ παντὸς πυροῦται, οὕτως ἡ Αἴγυπτος ἐκ τῆς θερμότητος διά παντὸς ζῳογονεῖ τὰ ἐν αὑτῇ ἢ παρ᾽αυτῇ ὑπάρχοντα.

xxii. How they signify Egypt

To write Egypt, they draw a burning censer and a heart above it, showing that as the heart of a jealous person is constantly aflame, so Egypt, through heat, forever vivifies everything that is within or near it.20

κγ᾽. Πῶς ἄνθρωπον μὴ ἀποδημήσαντα τῆς πατρίδος

Ἄνθρωπον τῆς πατρίδος μὴ ἀποδημήσαντα σημαίνοντες, ὀνοκέφαλον ζωγραφοῦσιν, ἐπειδὴ οὔτε ἀκούει τινος ἱστορίας, οὔτε τῶν ἐπὶ ξένης γινομένων αἰσθάνεται.

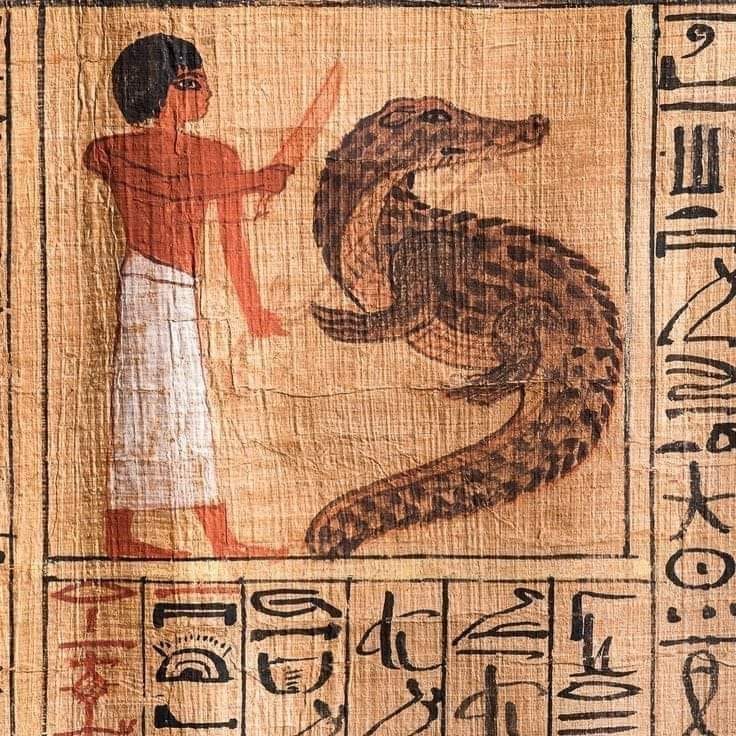

xxiii. How a man who has not travelled from his homeland

To signify a man of the homeland who has never travelled abroad, they draw a man with an ass’s head (onocephalus), because he has neither heard any stories, nor does he sense what is happening in foreign lands.21

© Sasha Chaitow and Black Letter Press, 2025. All rights reserved.

This is the last excerpt I shall be sharing from my Hieroglyphica; the rest is in the book!

Visit the publisher’s website here to read the full description, scholarly endorsements, and find ordering information and further details.

Wildish lists a third English translation: J. G. Mead, The ‘Hieroglyphica’ of Horapollo Nilous; Which He Himself Transmitted in the Egyptian Tongue, and which Philippus Faithfully translated into the Greek Language. With a Mystical Commentary. Edmonton: Jeffrey Mead, 2001. I have not been able to locate references to this book in any repository.

Leal, Pedro Germano Moraes Cardoso, “Reassessing Horapollon: A Contemporary View on Hieroglyphica,” Emblematica, Brooklyn Vol. 21, 2014: 37-75 (70). Translations of translations are notoriously problematic, as the following commentary demonstrates.

BoH xxiii-xxiv.

J.-L. Fournet éd., Les Hieroglyphica d’Horapollon de l’Égypte antique à l’Europe moderne (StudPAP 2), Paris 2021, p. 1-8. (7, n. 19).

For full bibliographical data and lists of editions see the Appendix.

Leal, “Reassessing Horapollon,” 43, n. 16.

Leal, “Reassessing Horapollon,” 70.

Fournet, “Les Hieroglyphica à l’Europe moderne,” 7.

Sbordone considers this “superfluous detail” from a Greek source and suggests it is an editorial insertion; he further claims the same for several other entries in his focus on distinguishing “authentic” Egyptian from Greek material. SbH, XLVI. However, in Kyranides, Book One, we have the line: “The nature of the crow, the bird, is the following: If the female dies, the male touches no other. Equally, the female does the same. So if the man wears the heart of a male crow and his wife that of a female, they will love each other for all their years.” Kyranides 1, B, 14-19, in Hermes Trismegistos, Complete Works, Vol. 4: Magic: The Kyranides, Athens: Kaktos, 2001, 851-3. Cf. M. Ruelle, F. De Mély, Les lapidaries de l’antiquité et du moyen-âge; 2. Les lapidaires grecs, Paris: Leroux, 1898-9.

Μονογενής [monogenēs] has two primary meanings: either an only (or only legitimate) child, only begotten (as translated by both Cory and Boas), or unique (born of a single parent, or indeed, self-generated. The translation ‘only-begotten’ clearly reflects the Nicene-Constantinopolitan creed in which “τὸν Υἱὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ τὸν μονογενῆ” translates to “the only-begotten Son of God.” There is complex theological reasoning and continued debate surrounding the connotations of the term, one of which is the question of procession versus creation embedded in the Filioque controversy. Although our author specifies that one of the meanings he is referring to does include procreation by a male alone (without gestation), I felt the theological connotation of ‘only-begotten’ will only cause confusion since this is not a Christian text. The late antique debate as to the nature of Christ and the Trinity raged even on the street in Asia Minor, according to St. Gregory of Nyssa (A. Vasiliev, History of the Byzantine Empire, Vol 1, 111.) As discussed in the commentary, members of Horapollon’s school were engaged in active efforts to counter Christian doctrine, so he would not have been unaware of it (also see discussion on the generation controversy in Part 4 of the commentary). Mythological and philosophical usage in ancient and Hellenistic texts clouds the issue further. The usage here clearly reflects the meaning ‘self-generated’ —αυτογενής—as seen within the text itself, a term that is not part of the Creed and is one of the main points of contention between pagans and Christians of this period. This is further strengthened by the use of the neuter —ές rather than masculine -ἦς suffix; he is referring to animals, not divine figures. This also counters Fournet’s claim that this demonstrates a Christian context for the composer of the manuscript (Fournet, “Horapollon,” op.cit.) To avoid the theological connotations I have retained the Greek term to demonstrate that it should be understood synchronically and not in relation to other uses of the word; if any such connections are to be drawn then we should consider Aiōn. Wildish selects ‘sole-begotten’ here in an attempt to avoid the same problem; I feel the word is familiar enough in direct transliteration to be acceptable in this form. Wildish, HSLA, 352-4. On the generation of beings also see in the Hermetica; CH XI.

ἀπηλιώτης: East wind, so named for από τον ήλιο (from the direction of the rising sun). Λίβας: West wind, so named for λιβάς (note accent shift), original meaning of “small stream, water source - stagnant water.” Also connotes vb. λείβω: “to drip - to pour” and hence the root of “libation.” These roots may connote a form of wordplay and secondary meanings, especially in relation to the repetition of emphasis on these cardinal directions: in the context of the definitions being given in this entry as well as the reference to water below, these lines may be read as: “the world is borne from sunrise to libation (ie, for the dead), while the path of the stars is from death to birth.” This may be worthy of further exploration. Definitions from EL, s.v. απηλιώτης; s.v. λίβας.

This sequence closely resembles veiled alchemical instructions as seen in the GAC, especially Zosimos.

Literally, through a form resembling the world, ie. the sphere.

Cf. Ploutarkhos, Isis and Osiris, 51: “…[F]or there is no such thing as a female beetle, but all beetles are male.” Cf. Berthelot: “The blood of a bull signifies the egg of a scarab.” CAG, Vol. 1, 12.

The dwarf-god Bes appears in the company of the Sun god in the form of a scarab beetle in scenes from the New Kingdom onwards and represents a guardian of Horus: “The scarab under the name of Khepry, was the form of the morning Sun, later associated with Horus, the infant god, embodying the “Sun-child.” The scarab between its forelegs pushed the Sun into the sky every day after its long journey in the dark… It was Bes, the god of infants and neonates, who protected the newborn sun.” Adrien Orosz, “Scenes with two Bes figures from Nimrud and the Second Step of Bes toward Globalisation,” Klaus Gets and Mark Geller eds., Esoteric Knowledge in Antiquity, TOPOI: Dahlem Seminar for the History of Ancient Sciences Vol. II, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, 2014, 21-36 (26).

ξόανον: image carved of wood, E. Ion 1403, X. An. 5.3.12: then, generally, image, statue, esp. of a god, Acus. 28 J., E. IT 1359, Tr. 525 (lyr.), 1074 (lyr.), B.Mus.Inscr. 1012 (Chalcedon, i B. C./ I A).

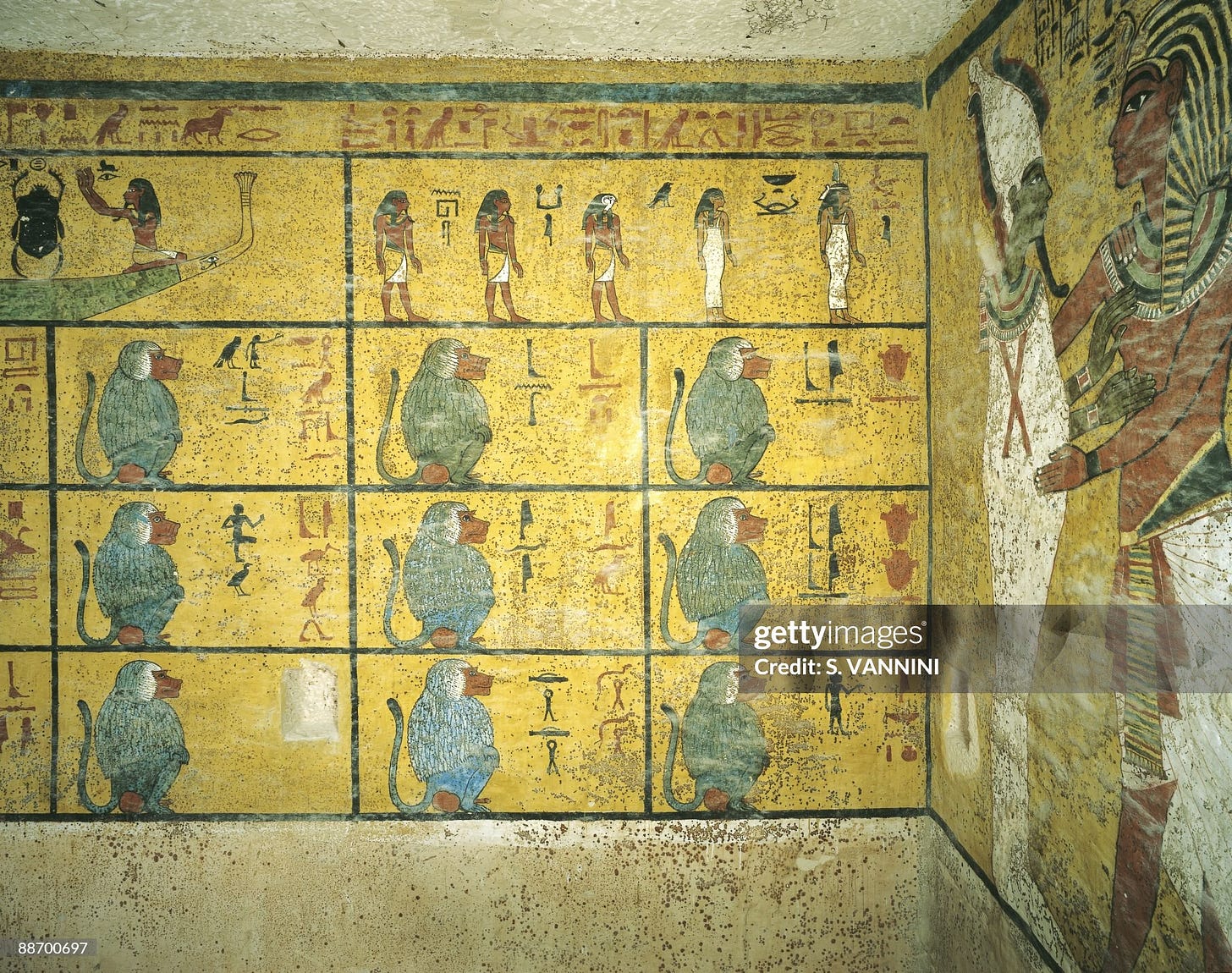

The “sun-god in the form of a cat” is a reference to the “Great Cat” of Ra, or “solar cat” Mau. Ra becomes the solar cat to slay Apep (Apophis) in the seventh hour of the Amduat adorning the walls of burial chambers and certain temples. The scene is also described in Spell 17 of The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Book of Going Forth By Day): “I am the Cat which fought near the Persea Tree on the night where the foes of Neb-er-tcher were destroyed. This male Cat is Ra himself and he was called ‘Mau’ because of the speech of the god Sa, who said concerning him: ‘He is like (mau) unto that which he hath made;’ therefore, did the name of Ra become ‘Mau.’” Papyrus of Nebseni, Brit. Mus. No. 9900, Sheet 14, ll. 16ff. In terms of temple depictions, one such scene is found in the 20th Dynasty Tomb of Inherkau at Deir-el Medina, Luxor. The writer/speaker of the exegesis may have known of a wooden statue still present at the temple of Ra-Atum in his day. The centre of a significant solar cult, it had largely faded by the time of Strabon (first century BC), who also gives some useful further insight: “At Heliopolis we saw large buildings in which the priests lived… But there are no longer either such a body of persons or such pursuits… They had… communicated the knowledge of the additional portions of the day and night, in the space of 365 days, necessary to complete the annual periods and at that time the length of the year was unknown to the Greeks… until later astronomers received them from the persons who translated the records of the priests into the Greek language and even now derive knowledge from their writings and from those of the Chaldeans.” Strabon, Geography, 17.1.29, in H.C. Hamilton & W. Falconer trans., London, George Bell & Sons, 1903.

These three types of scarab are also attested in the PGM; it is speculated that the cat-formed beetle refers to the sacred scarab (Scarabæus sacer), thought to be the solar beetle (κάνθαρος ἡλιακός, PGM IV.751-752). It is attested in two spells, one in which it is ‘drowned and mummified to wear as an amulet in a ritual of mystic ascent to witness the sun god;” in another to “cancel a love spell (PGM LXI.34). The “bull-shaped” beetle is thought to be the lunar beetle of the PGM (κάνθαροι σεληνιακοί, PGM IV.2457-2458, 2684-2691), used as offerings to the lunar goddess, “and once threatened by being suspended over a fire to compel a summoned deity, (called in this case a “bull-formed scarab”, κάνθαρος ταυρόμορφος, PGM IV.63-85). Korshi Dosoo, Thomas Galoppin, “Animals in Græco-Egyptian Magical Practice,” Magikon zōon: Animal et magie dans l’Antiquité et au Moyen Âge, Institut de recherche et d’histoire des textes, 2022, 203-256, (219, n. 19).

Sbordone identifies a Hermetic reference: “At one time, Hermes Trismegistus, when he was in Egypt, conjectured that a certain sacred animal dedicated to Serapis, urinated twelve times throughout the day, at equal intervals of time, this measured a day of twelve hours and since then, this number of hours has been preserved.” (Mario Vittorino, ad Ciceronis scripta rhet., Halm, Rhet. lat. min. 223). Also see Sbordone on the transmission of hourly timekeeping in Babylon, Egypt, and Greece as well as archaeological evidence for devices such as that described, SbH 45-49. He further confirms a connection with the twelve hours of Osiris’ passage through the underworld cited above (SbH 49) and Egyptian and Greek astrological practices. Photios records Damaskios ascribing the same habit to cats, equally used for timekeeping (“the cat distinguishes the twelve hours, urinating every hour of day and night, like a timekeeping instrument;” PH in Phot. Bibl. cod. 242, p. 343a), and a similar entry in the Physiologos. Also consider pseudo-Democritus on twelve hours of alchemical operations (III. XVI: “Sur L’exposé détaillé de l’Oeuvre: Discours a Philarète,” Berthelot, Traduction, 164, n. 5). In relation to Aiōn: “‘You who transform into everything, you are the invisible Aiōn of Aiōn (ἀόρατος εῖ Αἰὼν Αἰῶνος).’ This god who transforms into everything (ὁ μεταμορφούμενος εἰς πάντας) makes us think of the Sun who changes form on every one of the twelve hours of the day.” (PGM, XIII 63, from a prayer in the Kosmopoiia; cf III 494) in Festugière, Révélation, vol 4, 194, translation mine. Together with the reference to controlled release of water, timekeeping, and urination, it may reflect alchemical operations; urine signifies sulphuric acid in Zosimos (III. XXV “Sur L’Eau Divine), Berthelot, Traduction, 182); cf. Blemmydes, “Commentary,” in Berthelot, 425); but dehydrated corresponds to earth (Fragment attr. to Zosimos, V.II. “Travail des quatre éléments,” in Berthelot, Traduction, 323).

Both Ploutarkhos and Kyrillos (Cyril) of Alexandria designate this hieroglyph of the censer and heart as signifying the soul, rather than Egypt. Sbordone (67) identifies an allegorical substitution of “Egypt” for “soul” on account of the vivifying heat generation; this association between Egypt and heat is also found the in the Kore Kosmou, as is the designation of the Eye of the World. Cf. discussion in Bull, “Chapter 3,” Tradition, passim. Also see the following note.

This hieroglyph was used to designate Set (Ploutarkhos, Isis and Osiris, 30, 31, 50; Aelian, X, 28). Sbordone, following Lauth, suggests that this degree of contempt for someone who has not travelled reflects more the opinion of a Greek than an Egyptian, in the sense that one who does not visit Egypt remains ignorant of civilised life. He draws a parallel with Hermes Trismegistus in Stobaios (I, 49, 45, Vol I): and proposes a Stobaian Hermetic fragment as the source: “Horus said: “For what reason, mother, are the people outside our most sacred land not prudent and thoughtful in their thinking, like our people?” My trans. of Stobaios I.49.45 from Hermes Trismegistos, Complete Works, Vol. 3: Fragments, Testimonia, Athens: Kaktos, 2001; 712-13. Cf. Litwa, Hermetica II, 135. On this Sbordone remarks: “It follows that the former, due to their alleged mental inferiority, were considered on a par with barbarians by the Greeks.” Aside from this essentialisation on which we have already commented in the Introduction, these fragments have been identified as being among the most “Egyptian” of the Hermetic Corpus (see Jørgen Podemann Sørensen, “The Eye of the World, An Interpretation of the Kore Kosmou on its Egyptian Background,” Herme<neu>tica: New Approaches to the Text and Interpretation of the Corpus Hermeticum, Princeton University Colloquium, 2012; though some scholars consider them to belong to a separate, if related tradition (Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 141). If this is correct, then an Egyptian is asking why others are not as prudent, and not vice versa. In the Stobaian fragment I disagree with translating “συνετοί” as “wise” and “διανοίαις” as “deliberations;” there is a distance between σοφία and σύνεση or φρόνηση, and “deliberations” connotes something more specific; διανοίαις refers to thoughts or intellectual considerations, a different form of thinking than “to deliberate.” I also believe there to be grounds for considering this an alchemical reference; again see Berthelot, Traduction, 129; cf. Festugière “La création des âmes dans la Korè Kosmou,” 102–16, in which he notes that the composer of the text must have been aware of alchemical processes. In Bull, Tradition, 103, n. 34.

My favorite was the asshead. Prescient.

Now this is a headline that drives readership!