The Many and the One: What We Get Wrong About Greek Religion

How plurality and community shaped the gods, the city, and the self.

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the whole post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

The minute the words “rupture” and “continuity” enter the conversation, tempers flare. To talk about “polytheism” and “monotheism” in Greek history is to step into a live argument, not just among scholars, but among practitioners, believers, and anyone who sees their story reflected in the past.

Why does it matter whether the Greeks saw their gods as “many” or “one”? Or whether Christianity marked a clean break or simply the next turn in a winding road?

It matters because the words themselves: daemon, god, saviour, aren’t just historical artefacts. They are live wires: pick them up and you might get burned, or burn someone else.

The real danger is not disagreement, but the drift into wishful thinking and logical fallacies. Arguments built on appeals to authority, special pleading, ideologies, or straw-man caricatures don’t just obscure what happened; they fuel damaging narratives. That’s why I insist -sometimes to the irritation of all sides- on method, context, and evidence over rhetoric.

If you want a refresher on the most common traps, see the infographic below. It’s worth keeping in mind as you read.

I don’t approach these questions to win followers or support anyone’s prior convictions. My only discipline is to follow the evidence wherever it leads, even when it crosses boundaries others insist are fixed.

So, this is not a safe history lesson. It’s an attempt to do justice to the evidence, to show how Greek religious plurality survived rupture after rupture, and why our arguments about it today are, in truth, arguments about ourselves.

This essay doesn’t offer easy answers or comforting slogans. Instead, it asks what really happened: How did Greek religion sustain such a plurality of forms, in the face of so many changes? And why does that plurality still matter, perhaps now more than ever?

Fair warning: What follows is a true long-form essay (yes, you’ll need coffee). Every argument is footnoted and every shortcut avoided. If you’re after a “hot take,” this may not be the best place to start; have a browse here.

When we speak of “the Greeks” in antiquity, we are not referring to a monolithic people bound to a single city or uniform way of life. “Greek” identity was a dynamic, pluralistic tapestry woven across the Mediterranean world. From the Iberian Peninsula to the Near East, Greek communities interacted with diverse cultures, negotiated identities, and adopted new practices. 1

Yet, amidst this diversity, there remained common threads: a shared language, a pantheon of gods (often merged with local deities), and core cultural values, that bound these far-flung Hellenic peoples together. Modern scholarship emphasises that ancient Greek identity was never solely Athenian and not as rigidly separated from non-Greek “others” as once thought.2

Even the term barbaroi (“barbarians”) used to distinguish non-Greek speakers was a 5th-century Athenian concept too often generalised in modern usage.3 In earlier times and outside the Athenian perspective, interactions between Greeks and others were more fluid and varied by locale. The intensity and nature of Greek–non-Greek encounters differed from area to area, underscoring that the Greek world was not homogeneous but context-dependent. It was an evolving negotiation between local uniqueness and a broader Hellenic culture, demonstrating that “the Greeks” were united by a worldview and heritage even as they remained remarkably diverse.4

So, when we generalise about “the Greeks,” it’s easy to forget that we’re speaking of nearly 4 millennia of convoluted history, encompassing a host of tribes, both elite and lay populations, spanning three continents for a time, holding the longest-lasting empire in history.5 Much of this timeline survives only in fragments, epigraphs, and ruins. And narratives. Among those narratives, some are more accurate than others, but none is complete.

Faced with these gaps, historians turn back to what the ground, the stones, and the texts actually yield, however partial; those who lack that discipline weave patterns out of thin air. It is the difference between acknowledging a gap and documenting it, or filling it with whatever shape - or ideology - most appeals.

Where scholarship is bound to evidence, reconstruction often proceeds by pattern completion under uncertainty: the mind’s refusal to tolerate a blank space. I wrote recently about ideasthesia (our tendency to see what we expect rather than what is actually present). This is the same mechanism at work: once an idea has taken hold, we “see” it everywhere, completing patterns even when the material is missing. The difference is that in history, letting the idea lead the evidence produces a mirage.

The Archaic period, c. 800-700 BCE

For the earliest Greek religion, we rely above all on Hesiod and Homer. They are not neutral authorities, nor should they be read as timeless scripture. They are poets, each initially speaking - not writing - from a specific vantage point, with traditions shaped by the needs and expectations of their own audiences. We know that these epics were transmitted and adapted through generations of oral transmission, their shape shifting according to region and audience.6

Yet precisely because they are not gospels, the versions of their works that have reached show us a divine order in the act of being negotiated. In Hesiod, older powers are confined while others are confirmed or promoted; in Homer, gods contend, bargain, and reallocate their prerogatives among mortals and themselves. These narratives reveal a pantheon that never remained static, but was continually reshaped by conflict, settlement, and redistribution.

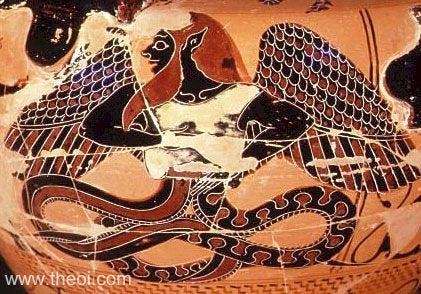

In the Theogony, the succession myth climaxes not with the annihilation of all chthonic powers but with their confinement. The Titans are cast into Tartaros, Typhoeus is buried under Aetna.7 They remain present, acknowledged, feared, even respected, but displaced from the surface of ritual life. The world is reorganised under the sovereignty of Zeus, who now redistributes timai: honours, prerogatives, offices to the Olympian gods.

The poem lingers over Hekate precisely to make the point.8 Unlike other Titans, her prerogatives are not diminished but confirmed and augmented: “in earth and in the unfruitful sea and starry heaven” she retains her share of power, able to give victory, prosperity, and protection across human life.9 In other words, the shift from Titans to Olympians is not a clean break but a redistribution of roles, the old given space in the new order. Even powers consigned to the depths are not erased; their place is marked. Those retained at the surface, like Hekate, are invested with new authority under the new regime.

Hesiod’s narrative reflects the political world of archaic Greece: the move from clan-based cults to centralised institutions of the polis, where older loyalties had to be tamed, incorporated, or formally retired.10 The divine order, like the civic order, is one of negotiation and reallocation. Already here, the pattern is visible: significant change is at hand, but important strands are carried forward into the new dispensation.

Aischylos and the Containment of the Chthonic

By the classical period, the same logic of negotiation appears on the civic stage. Aischylos’ Eumenides dramatises the transformation of the Erinyes, the ancient goddesses of blood vengeance, whose relentless pursuit of Orestes threatens to tear apart the city. At the climax, Athena intervenes: rather than annihilating the Erinyes, she reconstitutes them as the Eumenides, “Kindly Ones,” assigning them a new civic role as guardians of justice and fertility.11

Unlike Hesiod’s cosmic succession myth, here the drama resolves not by annihilation but by civic negotiation and settlement. Dangerous chthonic powers are not erased; they are mollified, granted cult, and given a controlled place inside the polis.