Why Not Every Ruin Needs a Saviour

Ghosts in the Stones and the Defilement of Memory (Thyrathen Crossroads)

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

If you’re new here, Thyrathen is my independent research platform on Greek magic, folklore, and cultural realities. Regulars get deep research, translations, and insider dispatches like this, from the crossroads where Greece meets the world. Subscribe below or check the archive for more.

There’s a peculiar tradition in these parts: every summer, just as the first budget flights touch down, a familiar procession begins—tourists peering into ruined chapels, shaking their heads, and proposing a whip-round to “fix” the scenery. Invariably, someone wonders aloud why Greeks haven’t thought to renovate their own history for the comfort of visitors.

One can hardly blame the all-inclusive cocktail tourists—ruined chapels are as exotic as it gets after your third Aperol spritz. But lately, even spiritual entrepreneurs and the odd scholar seem keen to rescue Greek ritual and language from the locals. The irony, as long-time Thyrathen readers will know, is that these supposed “relics” are not relics at all. The threads I follow in these pages—from Byzantine exorcisms and saints’ feasts to folk magic and crossroads rites at midnight—are not echoes of a vanished world, but proof that Greek tradition remains stubbornly alive, inconveniently local, and often invisible to the well-meaning gaze of outsiders.

So when I write about a roofless chapel in a ghost village, it is not nostalgia. It’s to show why the memory, ritual, and contested meaning embedded in these stones matter at least as much as their restoration. This isn’t a distraction from the questions of magic, folklore, and continuity that run through this publication, but the crucible where these questions are fought over, bottled, and sometimes lost in translation.1

Whether you come seeking a sunburn, a séance, or a footnote for your next monograph, consider this your field guide to why Greek ruins, rites, and mysteries rarely benefit from outside improvement—and why, when it comes to memory and meaning, the real secrets aren’t always for sale.

Who gets to decide what’s worth preserving, and what counts as “authentic”? If you’ve ever tried to revive an ancient practice—or wondered why the locals are suspicious when foreigners want to help—read on, this is the real backstage tour.

This is not the briefest of essays, but then again, neither is Greek history. If you need a break, pour yourself something cold and come back when you’re ready—ruins are patient.

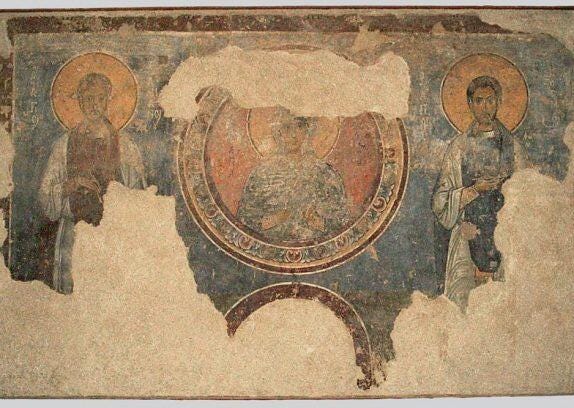

Taxiarchis chapel

In a remote Corfu mountain village, an 18th-century Orthodox chapel stands roofless, its frescoes fading under sun and rain. Tourists peer in, aghast.

“Why don’t you fix it?”

“Don’t you care about your heritage?”

“We should start a fundraiser”

This was a real post seen on social media in early June 2025, which sparked a debate along the lines of the (real but anonymised) remarks above.

Though seemingly well-meaning, these reactions reveal a deeper assumption: that outsiders better understand heritage preservation than local communities.

What outsiders seldom realise is that these ruins are shaped by far more than neglect. They are the living evidence of memory, economic and social catastrophe, government failure, and repeated outside interference.

Law and Memory

Firstly, there is a legal reality: the Greek Orthodox Church owns the majority of churches in Greece, including ruined ones. These are not public property and cannot be intervened upon at will.2

Even minor interventions require explicit Ministry of Culture approval, —a policy that frustrates many locals and outsiders alike. Good intentions alone are not enough; unauthorised intervention is both misguided and illegal. Permits must be formally requested by the Church or legal owner (often unknown or deceased), and any interventions carried out by licensed conservators.3 While this slows progress, it reflects both legitimate concern for preservation and, admittedly, longstanding bureaucratic challenges.

The Ministry prioritises flagship sites, informed by objective interest as well as local sensibilities. Greeks have long practiced a form of collective memory that leaves ruins standing as silent witnesses.

After the Persian Wars, Athenians chose not to rebuild destroyed temples, precisely so they would forever remind future generations of past violence. As Diodoros of Sicily records in the Oath of Plataiai:

ὁ δὲ ὅρκος ἦν τοιοῦτος: οὐ ποιήσομαι περὶ πλείονος τὸ ζῆντῆς ἐλευθερίας, οὐδὲ καταλείψω τοὺς ἡγεμόνας οὔτε ζῶντας οὔτεἀποθανόντας, ἀλλὰ τοὺς ἐν τῇ μάχῃ τελευτήσαντας τῶν συμμάχων πάντας θάψω, καὶ κρατήσας τῷ πολέμῳ τῶν βαρβάρων οὐδεμίαν τῶν ἀγωνισαμένων πόλεων ἀνάστατονποιήσω, καὶ τῶν ἱερῶν τῶν ἐμπρησθέντων καὶ καταβληθέντωνοὐδὲν ἀνοικοδομήσω, ἀλλ᾽ ὑπόμνημα τοῖς ἐπιγινομένοις ἐάσω καὶ καταλείψω τῆς τῶν βαρβάρων ἀσεβείας.

The oath ran as follows: "I will not hold life dearer than liberty, nor will I desert the leaders, whether they be living or dead, but I will bury all the allies who have perished in the battle; and if I overcome the barbarians in the war, I will not destroy any one of the cities which have participated in the struggle1; nor will I rebuild any one of the sanctuaries which have been burnt or demolished, but I will let them be and leave them as a reminder to coming generations of the impiety of the barbarians."4

This was not neglect but a political and cultural statement. Similarly, when Athenians rebuilt the Acropolis walls, they deliberately incorporated damaged marble blocks from destroyed temples into the North Wall, as a visible reminder of Persian destruction and a memory fragment of trauma and resilience.5

Today, Greek communities sometimes leave ruins untouched due to limited financial resources—but also as a warning to future generations. They are trauma made visible, not a dark chapter to be erased. But this is only part of the story.

Contested Heritage

The question of how to handle ruins—whether to leave them as scars, revive them, or reimagine them—goes far beyond Greek realities alone.

Internationally, the conservation of historic sites reflects multiple, often competing schools of thought. Western conservation charters (Ruskin; Venice Charter 1964) legitimise preservation approaches that stabilise structures while honouring their decay, allowing their "scars" to bear witness to history.

Interventionist schools—restoration and reconstruction—seek to return structures to earlier states, often under the guise of restoring dignity or function, but frequently blurring historical authenticity. Such approaches, especially when driven by external actors, embody a colonial gaze: privileging outsider visions of heritage over local meanings and erasing context in favour of commodified beauty.6

In recent years, the philosophy of managed decay—or “conservation of ruination”—has gained prominence, particularly in Europe, as a deliberate, ethical choice.7 This internationally recognised model advocates maintaining ruins in a stable, safe state, but not erasing the visible traces of time and trauma. It is a conscious alternative to both aggressive restoration and abandonment. Ruins are seen as living testimonies, not problems to be solved for the aesthetic comfort of outsiders, and the model aligns closely with Greek sensibilities, where the visible scars of history are not just tolerated but actively valued.

Old Peritheia: Too Much of a Good Thing?

The boundary between preservation and commercialisation can be ambiguous. Old Peritheia in Corfu encapsulates this double-edged tension.

Peritheia was founded in the 14th century, when coast dwellers fled pirate raids and malaria. It was abandoned due to 20th century tourism and became a ghost village. It is not that tourism ousted the locals - they fled the grind of rural life for the promised riches of the nascent tourist industry, in successive waves of urbanisation that decimated the villages and led to significant social rifts - which I have witnessed in my own family.

Peritheia’s recent revival was sparked not by grassroots local demand but by an Anglo-Dutch couple who restored several ruins and promoted the village as a “hidden gem.” This intervention drew global attention and investment, encouraging some local return, yet the terms of this revival were largely set by outsiders, shaping both what is preserved and who benefits.8

This project prevented Peritheia from being left to nature, demonstrating how commercial initiative can help revive such places and create livelihoods. However, the revival was framed and curated through an outsider’s lens, repackaging authenticity for the tastes and expectations of affluent tourists. As Perithia’s story circulates on travel blogs and Instagram, its authenticity becomes another heritage product: a consumable “secret Greece” for the global market. Meanwhile, local stories are subsumed by narratives defined by foreign capital and taste—whatever the original intent.

Peritheia thus stands as a case study and cautionary tale about the persistence of the colonial gaze—even in projects that appear, on the surface, to “save” neglected heritage. Is the heritage in the buildings, or the human stories and scars lost to fresh paint? This complexity is not unique to Greece, but it does highlight the need to interrogate whose vision of preservation is being enacted, and for whom.

Greeks have a deep-rooted aversion to the commercial exploitation of antiquities and historic buildings—a stance rooted partly in communal tradition and partly in left-leaning egalitarian values that span the political spectrum. There’s a widespread conviction that heritage belongs to the people, not to private owners or individual market interests.

As a result, abandoned sites—whether chapels, palaces or ancient ruins—are typically repurposed for public functions such as museums, municipal libraries, or cultural centres. This model resists the idea of allowing narrow visions and profit motives to prevail. Only recently have private, Greek-led organisations like NEON begun collaborating with the state to fund rehabilitation, but always with the condition that restored sites remain in public ownership and open access . Attempts to impose conspicuous elitism—particularly by transforming these sites into exclusive hotels or luxury venues—are met with public suspicion and often protest.

Yet tourists, as spenders, receive a different reception—one that masks the everyday tension between commodified appearance and civic values. Abroad, these nuanced whole-of-society ethics don’t exist, which is why foreign expectations about “fixing” ruins often clash with local values in the first place. There are also deeper dimensions regarding the social impact of such interventions, but those must wait for another time.

From War to Ruin: 20th Century Upheaval

To understand why so many monuments seem abandoned, one must understand the devastation of modern Greek history. The Nazi occupation left swathes of the country in ruins.9 Villages were torched, churches burnt, populations decimated. This was swiftly followed by a civil war (1946–49) so brutal it left whole regions depopulated, villages empty, and the scars of fratricidal violence embedded in the very walls of the cities and country fields with mass graves.

The Cold War, and later the dictatorship of 1967–74, produced a government apparatus that centralised control. With the restitution of democracy came bureaucratic paralysis, political patronage, and waves of emigration gutted rural communities. EU accession in 1981 brought funds, but also more red tape, and often the priorities of Brussels or Athens superseded the actual needs of local communities or the realities of depopulation and poverty.10 Tourism became a rich seam and new source of development, but at significant cost.

Cultural Imperialism and the “Fix-It” Mentality

Here the colonial gaze returned in force. Time and again, outsiders—tourists, philanthropists, foreign governments—arrive, eager to rescue, activate, or “save” monuments presumed to be at risk from Greek incompetence. The pattern is not new: Lord Elgin justified stripping the Parthenon because Greeks, under Ottoman occupation, were disenfranchised and did not have a say in their own legacy. Today, similar attitudes reappear in proposals to “restore” roofless chapels or commercially “repurpose” sacred spaces, often overriding local sensibilities, religious law, or historical reality.

This history is within living memory, and personally I have had countless encounters with this mentality. When I once led a conference tour on Samothrace, one American visitor thought the ruins were replicas, and that the ancient site was a kind of reconstructed theme park. She looked at me in disbelief when I confirmed that the ruins were genuine and over 2500 years old, saying: “In that case, why have they not been renovated?”

In Corfu, the social media debate that triggered this post was sparked by a roofless 18th-century chapel on a treacherous mountain trail. Outsiders called for fundraising and foreign intervention. Most of the village has been bought up by foreign expats, while the few remaining locals still perform devotions beneath the open sky, keeping the site alive through ritual rather than reconstruction.

The same gaze appears in everyday life: tourists complain that my four-century-old, fully renovated apartment building is “too old,” as if age were a defect; others grumble about unfinished buildings marring their idealised holiday destination, not realising these are sometimes the last trace of families dispersed by crisis or tourism itself; or new rental complexes being built as and when resources allow.

Meanwhile, multinational resorts transform what was green space and family businesses into exclusive compounds, closing off beaches from local access and driving up prices—changes that rarely draw protest from the same visitors who bemoan “neglect.”

These are not the failures of Greek culture, but symptoms of a relentless pressure to perform heritage for outsiders while survival for locals grows ever more precarious.

Tourism: Salvation and Ruin

Tourism is both Greece’s lifeline and its undoing. It accounts for nearly 20% of GDP, with one in five jobs linked to the sector (OECD, 2022). Yet the costs are immense.

Mass tourism has driven overdevelopment, especially in the islands and on coasts.11 Local communities are hollowed out as short-term rentals and global chains displace family businesses; property prices soar beyond local means, and social cohesion breaks down. In places like Santorini and parts of Corfu, the very landscapes that attract visitors are being destroyed for short-term profit, while infrastructure buckles under the strain.

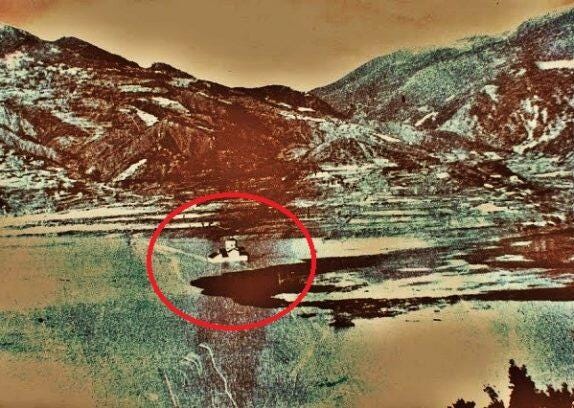

The picture above is next to the coastal village where I grew up: once a traditional resort with local colour; now the locals have been driven out and the huge complexes dominate the coastline. Mine is one of only three local families to remain in my area; all other buildings have been converted to holiday rentals. All around me, dense woodland is being replaced by new rental builds… in stages. I am coming under pressure from neighbours to bring down the tall (and old) trees on my own land because they “obstruct the view … haven’t you seen the nice lawns and low shrubbery at the hotels?” I am holding out, but am one of very few. Those who resist such “progress” are frequently mocked.

It would be dishonest to pretend that all wounds are inflicted from outside. Greek bureaucracy, political clientelism, and sometimes sheer apathy have also played their part. The tragedy is that international pressure and internal dysfunction so often reinforce each other.

When the Sacred Becomes Spectacle

These dynamics play out in sacred spaces, too. A few months ago in Corfu, I faced another example of well-meaning interference. Some europhile Greeks proposed holding concerts in the British Cemetery to raise funds for its upkeep. For them, it was a picturesque venue to “activate” - and is listed as a key attraction on tourist websites due to the Commonwealth war graves and historical connections.

However, the cemetery is also the resting place of many recently deceased with living relatives, for whom this is sacred ground. My mother’s funeral there, at the end of 2023, was one of the last before the cemetery closed to new burials. While planting flowers on my parents’ grave, I’ve had tourists stop and stare at me as if I were part of the scenery. Despite the British connections, many families with relatives resting there are mixed and bicultural like myself; to our sensibilities, using a cemetery as anything other than a place of respect and mourning is unthinkable.

Nor is it limited to cemeteries or famous ruins. At my best friend’s niece’s christening, and at my cousin’s wedding, tourists wandered in during the church services—in beach gear, snapping photos, treating private family rites as local colour for their holiday albums. Out of habit or hospitality (call it what you will), we wearily nodded them in, but there’s a point at which even the friendliest welcome starts to feel like submission to someone else’s script.

This dissonance reflects how outsider tastes are treated as the ultimate measure of value, the refusal to engage with Greek voices as equal partners, and the eagerness of some Greeks to silence dissent to appear more “European.” This is not just cultural misunderstanding—it’s political, and a form of self-erasure.12

Beyond the stones, the same attitudes surface in online forums, where Greek funeral rites and mourning practices are mocked as “too dramatic,” with foreigners proposing that “someone really needs to show these locals how to do things properly.” (actual verbatim statement from a British expat in Corfu).

Orthodox Christianity, which infuses every aspect of Greek memory and identity, is routinely misunderstood or reduced to caricature by foreign observers, even as it provides the last link to communities hollowed out by migration and loss, and assaulted by Europeanisation.

Case studies

In Corfu’s abandoned mountain villages, locals continue to perform annual processions to roofless chapels, lighting candles and singing hymns. The ruined church of Agios Nikolaos at Perithia, despite lacking a roof, hosted annual vespers and small liturgies under the open sky (Corfu Ephorate of Antiquities Report), and has been restored since 2010 through the private enterprise described above.

In Epirus, the half-collapsed chapel of Panagia Spiliotissa near Aristi (burned and pillaged by the Ottoman Turks in the 19th century, then damaged irreversibly by an earthquake), sees local villagers gathering each August for a panigyri, setting up icons among the ruins and chanting prayers.

Water, water, everywhere

Likewise, churches submerged through natural disaster or human intervention (creation of reservoirs), are still revered, with folk rituals taking place on specific feast days, as with the submerged church of St. Barbara in Drama, which I have written about here.

A rare, highly decorated 9th century Byzantine church once stood on the banks of Acheloos river, in the village of Episkopi, in Evrytania. The majority of the frescoes and icons were salvaged, exhibited worldwide, and moved to a permanent wing of the Byzantine Museum in Athens. It was well-preserved and fully functional until it was submerged in 1965 to create a hydroelectric power station. The church still stands beneath the waters, and local legend has it that sometimes they can still hear its bells.

Kallio village in Fokida, built on the site of the ancient city of Kallipolis, was expropriated in 1969 and submerged in 1981 to create a reservoir for the city of Athens. The village community relocated, but their loss remains within living memory.

A recent short essay film by creative duo Ionian Bisai and Sotiris Tsiganos, Neromanna (Water-mother), subtitled “How does one recount the history of a place that no longer exists?” reflects precisely the nature and character of Greek reclamation of memory and processing of loss through underwater filming and eye-witness accounts, alongside dedicated events and installations.

Neromanna (2017). Directed & Produced by Ionian Bisai / Sotiris Tsiganos.

These aimed to “re-inhabit the drowned village,” and the creators describe their project as “a potentially ideal place for the practice of the social rituals of the community, while also seeking opportunities for a critical confrontation with contemporary social history.”

The Altar of the Twelve Gods

In 2011, a furore erupted over the decision to rebury the 6th century BCE Altar of the Twelve Gods excavated near the railway lines at Thiseio, below the Acropolis. The Greek Supreme Court upheld the archaeological decision to rebury it. The stated reasons were twofold: first, full excavation would require major and costly disruption to essential infrastructure; second, the security and proper conservation of the altar could not be guaranteed under current conditions. The solution was to rebury the altar. This was justified as a practical decision to preserve the monument in situ for a future time when it might be adequately protected and responsibly displayed. Many archaeologists, local polytheists, and ordinary citizens disagreed strongly, but were overruled. Many of the issues I raise here were central to the debate.

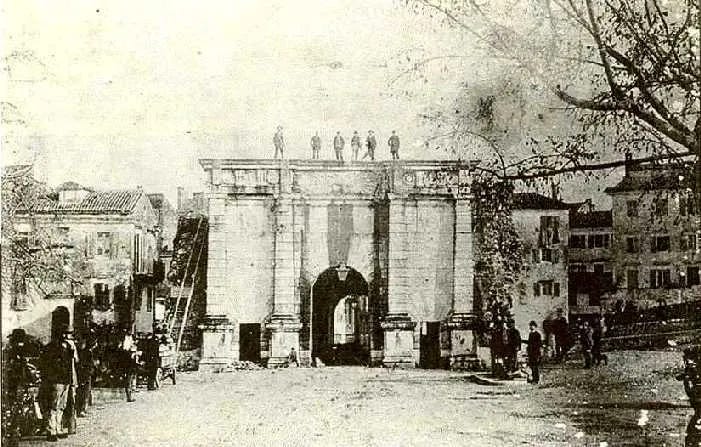

Porta Reale, the Royal Gate

A similar situation occurred with a Venetian gate in Corfu. Erected by the Venetians between roughly 1576 and 1588 as one of four principal city gates fortifying the city, Porta Reale once marked the entrance to Corfu’s walled town (the others being Spilia, Agios Nikolaos, and Porta Remounda, demolished during British rule). The official reason given for its demolition in 1893 was city expansion: as social divisions blurred and villagers - whose access to the city had been strictly regulated - were permitted to take up residence there.

Porta Reale, long a symbol of royal authority and Venetian order, was ultimately dismantled amid heated political conflict—its removal serving both practical needs and clear political aims. Some of its parts were repurposed in other construction work. An uproar ensued when the foundations were uncovered during recent paving works, with locals campaigning for full excavation and conservation of these elements. They were ultimately reburied following the same rationale as the case of the Altar of Twelve Gods.

Greek ruins, then, are not the simple result of indifference. Sometimes they are preserved intentionally, as scars of past violence, the last traces of communities destroyed by war, depopulated by emigration, bled dry by economic collapse, flooded to serve greater needs. Sometimes local law, bureaucracy, economics, or religious sensibility make “fixing” impossible.

In all cases, to accuse Greeks of “neglect” is to ignore the brutal realities of a country still struggling to reconcile memory, survival, and identity, to resist the flattening gaze of outsiders who see picturesque decay at best, but all too frequently, as the supposed failings of a backward culture which then justify heavy-handed intervention.

Even the Venice Charter recognises that a monument’s scars and setting are part of its meaning. Ruins in Greece are as much witnesses to history, crisis, and cultural imperialism as they are testaments to faith, forgetfulness, or indeed, attempts at modernisation.

The Problem of the Parthenon

In stark contrast to such examples, the “Sacred Rock” of the Acropolis was recently covered in reinforced concrete—ostensibly to make it more accessible and prevent accidents among the summer crowds. Officials stressed that the new pathway is reversible, laid over a protective membrane so it can be removed without damaging the ancient stone.

Critics, including former site architect Tasos Tanoulas, counter that detaching the concrete would require power tools and risk further harm. Greek academic Yiannis Hamilakis has called it a “barbaric intervention” and “attempt to recreate an imagined fifth century BC Acropolis, a neo-classical colonialist dream” that competes with and diminishes the natural grandeur of the hill, accusing the authorities of privileging photo‑op access and mass tourism over conservation.13 The intervention has caused increased flooding at the site and the flow of crowds has become almost unmanageable, raising questions about the safety of the monument.

Government spokespeople insist the work improves accessibility and can be reversed within a day if needed, but the broader debate lays bare the tension between the perspectives of the Greek public, intellectuals, specialists, politicians, and the relentless demands of the tourist gaze.

The Acropolis, then, stands as a stark example: even at the very centre of Greek identity, the pressure to “improve” heritage sites for outsiders can overwhelm local priorities, unleashing controversies that echo far beyond the Parthenon itself.

It’s this same pressure—often dressed up as rescue—that shapes so many decisions about what to preserve, what to restore, and whose vision of history prevails. The urge to “save” Greek ruins, whether by pouring concrete or mounting campaigns from afar, is rarely harmless, even if well-intentioned. Too often, it repeats the patterns of cultural imperialism that have long haunted Greece’s relationship with its own past.14

Cultural Imperialism Disguised as Rescue

The notion that “foreigners must intervene because locals are incompetent” stems from a colonial-era attitude which assumes Western expertise is superior. This imposes foreign aesthetic values on local heritage, reflected in both tourist promotions and the impact it has on local life, and the tensions surrounding such monuments.

It ignores the cultural meaning of ruins in local memory, whereby their renovation for commercial or apparently eco-friendly purposes erases the layers of history that went before. This is precisely what scholars call the colonial gaze.15

Foreign “rescue” can become an act of memory subjugation if it disregards local narratives or religious significance. And even if encouraged by some locals who feel that even commercial repurposing is better than decay, questions of hegemony and interference remain.

Consecrated ground

In the case of churches specifically, another profound misunderstanding is theological. In Western traditions (e.g. Roman Catholicism), a church can be “deconsecrated” and converted into secular use. In Orthodox Christianity, the notion of deconsecration does not exist: even a ruin remains holy ground, and this is enshrined in law (590/1977). Turning it into a museum, café, or concert hall would be viewed as sacrilege.

Thus, proposals to “re-purpose” abandoned churches or holy ground for cultural uses clash with deep religious sensibilities, and add a dimension to such repurposing in other cultures where Orthodox churches have been appropriated by the occupying culture - such as Aya Sofia. Ancient sites are afforded similar respect regardless of their pagan roots.

The Value of Scars

Many Greek communities perceive decay not merely as loss, but as evidence of survival through centuries of history, war, and social change:

“Ruins are palimpsests, bearing witness not only to what they were built for but to everything that has happened since.”16

Rather than being quick to erase time’s traces, we need to consider their role as deliberate markers of collective memory:

‘Memory needs places. It clings to objects, spaces, buildings, landscapes.’17

Just like in antiquity, in modern Greece, ruins may remain standing because it has become part of the community’s memory landscape—a ‘figure of memory,’ as Assmann calls it. Repairing or rebuilding isn’t always the goal; sometimes, the visible traces of damage themselves hold historical and cultural meaning. Hence, leaving some monuments in ruin can be an act of profound respect for history. In Greece, these scars are part of our cultural DNA, and “neglect” has deeper dimensions.

A Comparison: Glastonbury Abbey?

A useful question for foreign critics is: Why do the British leave Glastonbury Abbey and countless other monastic ruins untouched? These monasteries were destroyed during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century, and their ruins have a history of being pillaged for spolia, redecoration, and botched repairs - much like those for which Greece is heavily criticised by outsiders18. Glastonbury Abbey remains a spectacular ruin, open to visitors, but never rebuilt.

The British, like Greeks, have come to value ruins as symbols of historical events, memory, and identity. Glastonbury Abbey’s roofless arches speak of religious upheaval, royal authority, and national transformation - as well as how societies treat their ruins. Its ruin has become part of its narrative. Multiple such examples exist around the world.

Thus, even nations wealthy enough to rebuild historic sites sometimes choose to preserve ruins as powerful testimonies to history. Greece makes the same choice — and should not be judged by standards that even the West does not consistently apply; nor indeed critiqued for past practices that are equally seen the world over.

Economic Reality

Greece has over 15,000 Byzantine and post-Byzantine monuments (Greek Ministry of Culture data). Conserving them all is financially impossible. A single conservation project for a small painted chapel may cost between €100,000 and €500,000. Restoration of frescoes in Osios Loukas Monastery, Boeotia, exceeded €1 million.

Authorities must prioritise monuments of historical or artistic significance. Furthermore, poor restoration can do more harm than good, and this was a key argument used in the cases of reburying the excavations noted earlier. Arthur Evans’s reconstruction of the Minoan palace at Knossos is another stark example. In the early 20th century, Evans rebuilt sections of the ruins using reinforced concrete and brightly painted fresco reproductions based on his own theories about Minoan society. The result is a site that reflects early 20th-century fantasy more than Bronze Age reality—a cautionary tale about how reconstruction can overwrite history.

Cultural Self-Determination Beyond ‘the West’

Greece’s heritage does not exist to be “saved” by outsiders. We are neither a cultural charity case nor a backdrop for Western nostalgia. Our monuments, churches, and ruins are embedded in histories, legal realities, and forms of memory that cannot be reduced to simple binaries of preservation or neglect. While Greece stands at the crossroads of East and West, its identity and practices cannot be subsumed under either.

This is not to romanticise decay, nor to claim that all ruins are sacred, but to insist that meaning, use, and value are locally defined and historically contingent.

The “Disneyfication” of Greece

The reality is that many visitors to Greece—tourists and, at times, even foreign scholars—see local people as stewards or service providers for external experiences and narratives. Greeks are often expected to perform hospitality, supply “authenticity,” and maintain a picturesque landscape for others’ consumption, while having limited authority in shaping how their heritage is presented or understood. This “Disneyfication” of Greek culture is well-documented and forms part of a broader expectation that Greece serve as an open-air theme park, shaped to satisfy the imagination of outside audiences.19

Similar asymmetries appear within academic fields. In Classics, for example, non-Greek perspectives have traditionally dominated, often casting Greeks as custodians rather than full participants in the interpretation of their own history. Persistent structural biases in editorial policy, hiring, and funding have been documented.20 These dynamics are not merely abstract: they influence research priorities, public understanding, and resource allocation, with long-term effects on both cultural policy and community sustainability.

(And if anyone pipes up that this is merely “complaining about microaggressions” - actually said to me in response to this piece - I’ll file it under reasons the field still can’t hear itself think beyond Oxford and Harvard.)

Greece is not a museum, a backdrop, or a fantasy park. It is a country whose memory and contemporary realities are shaped by, but not reducible to, its engagement with outsiders. Recognition of this complexity is essential if meaningful partnership, and not mere performance, is to be achieved.

Autonomy, Not Isolation

Arguments that “if you cannot save your heritage, let us do it for you” echo old justifications for foreign intervention. The notorious case of Elgin and the Parthenon marbles rested on the supposed incapacity of Greeks to steward their own legacy—a trope that persists today, if in subtler forms.

To demand the right to determine the fate of our monuments is not nationalism, but cultural self-determination. This is granted and vigorously protected with respect to African and Asian cultures, yet when it comes to Greece, the double standards are painfully visible. Greek debates about restoration, reuse, and memory are often intense and self-critical. Collaboration and assistance from abroad can be invaluable—when grounded in respect for local law, context, and the living dimension of heritage.

There is no single “Greek approach” to ruins: attitudes and practices are contested, and priorities shift in response to legal, economic, and cultural change. What unites them is a refusal to allow outsiders—however well-intentioned—to overwrite the meanings or memories that remain attached to place.

Respect and Partnership

Neither nationalism nor nostalgia can serve as the sole answer to complex questions of heritage. If some of this sounds pointed, it is because the pressure on Greece to “perform” for outsiders has rarely been matched by an equivalent openness to local knowledge or living culture. The goal is not exclusion, but mutuality—an approach already enshrined in best practices from ICOMOS to the Venice Charter.

International expertise, technical support, and funding are all welcome—when they are offered in partnership, not as a form of rescue. Preservation is not always a matter of fixing stones or erasing scars. Sometimes, the most responsible choice is to safeguard the memory and dignity embedded in what remains—even when that means accepting ruination as part of a site’s ongoing story.

Lest I be misunderstood, this is categorically not a defence of neglect, nor a claim to cultural superiority: my aim is to insist on a fuller account of what is at stake, and whose voices get heard. As seen in the Parthenon debate, there are vast divides between Greek people and their politicians; but these are our own issues to tackle. Greece’s challenges are as much internal as external, and genuine conservation always benefits from shared expertise. The question is not whether help is welcome, but on whose terms—and with what respect for the living meaning of place.

True respect for Greece’s ruins—and those of any country—begins with listening, learning, and recognising that memory, meaning, and belonging are never the sole property of outsiders.

Anyone who read this far is entitled to an honorary Greek grandmother—and a glass of ouzo! You’re the people I write for!

A note on transparency:

It is no secret that I am half Greek and half British, with a mixed Mediterranean heritage reaching both east and west. Bicultural and bilingual, I have spent my whole life translating my understanding of each culture into the other, and only recently have I begun to articulate these perspectives in a professional setting. My academic training is British and American, and this inevitably informs my approach. Throughout, I have sought to maintain scholarly integrity—grounding my arguments in evidence and critical analysis. My occasionally sharp tone should not be mistaken for bias; it reflects frustration with persistent double standards, not a partisan agenda. My sole aim is to ensure that Greek voices have an equal seat at any table—academic, political, or informal—where their own history and heritage are discussed, and to insist that they receive the same respect routinely extended to other historically marginalised cultures.

Housekeeping

Thyrathen is evolving! Regular readers will be aware I’ve been experimenting with post formats: for the next few months I will be producing three categories of posts, and welcome feedback and requests:

Thyrathen Crossroads are free investigative dispatches sitting at the literal crossroads where explorers of Greek topics meet Greeks, that liminal space where our worlds overlap but get lost in translation. They are discussion pieces tackling some of the most stubborn misunderstandings about Greek history, ritual, and culture. They drop once a month.

Thyrathen Fragments are also open-access pieces: more focused glimpses into lesser-known traditions, regional practices, or locations, which showcase living reality and memory, or act as orientation for free subscribers. Also once a month.

The main research essays and translations remain exclusive to paid subscribers, and continue as the backbone of my work. These are building toward books, offering new translations, original scholarship, and careful analysis that you won’t find anywhere else. They drop every 2 weeks, alternating with Crossroads and Fragments.

Occasionally I may compile dossiers on themes investigated from various angles and make them available for paying subscribers or as one-off downloads. Let me know in the comments whether this would be of interest!

If you’re curious, these open posts will give you a sense of what Thyrathen is all about, as I trace threads of continuity - and severance - through the Greek landscape. To follow the deeper story through the work that challenges assumptions by building the scholarly evidence with insider insight into what Greek heritage really means—I invite you to subscribe for full access. This enables me to continue this work and supports independent scholarship.

This article is free for all subscribers—a pause between more research-heavy topics. Next week, I’ll be sharing Part 1 of my translation of the ethnographic piece on Byzantine magic. If you’re curious about real Greek culture instead of well-meaning fantasies, I’d love to have you subscribe and help keep this work going.

Herzfeld, Michael. Ours Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern Greece. Princeton University Press, 1982; Gourgouris, Stathis. Dream Nation: Enlightenment, Colonization, and the Institution of Modern Greece. Stanford University Press, 1996; Tziovas, Dimitris. Greece in Crisis: The Cultural Politics of Austerity. I.B. Tauris, 2017.

Under Greek law ( 590/1977, Art. 1–2), Orthodox churches (including ruins) are ecclesiastical property. Monuments built before 1830 automatically qualify as archaeological sites (3028/2002; Art. 2.1). A number of chapels qualify as private property, but come under the same legislation.

Ministerial Decision ΥΠΠΟ/ΓΔΑΠΚ/ΔΣΑΝΜ/Φ38/56097/2685/20-11-2008, published in Government Gazette 2458/Β/2008.

Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XI.29.3 (Loeb Classical Library, trans. C.H. Oldfather)

Camp, J. (2001). The Archaeology of Athens. Yale University Press, p. 64–65.

Ruskin, John. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. 1849; reprint, Dover Publications, 2001.

International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter). ICOMOS, 1964

Edensor, Tim. Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality. Berg, 2005.

Macdonald, Sharon. "Preserving the Ruins." International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1–17.

Sakalis, Alex. “Greek Revival: How Corfu’s 14th‑Century Ghost Village Came Back to Life.” The Guardian, 17 Oct. 2021; https://old-perithia.com/blog-pr-publicity/

As Mazower documents in Inside Hitler’s Greece and After the War Was Over

(Herzfeld, 2002; Mazower, 2015; Voglis, 2002.)

as documented by UNESCO and Leontidou (2020).

The sociological and ethnographic impacts of these phenomena are exhaustively explored and traced in Michael Herzfeld’s Cultural Intimacy and nearly all works by Charles Stewart.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/2/acropolis-pathway-restoration-project-met-with-bumpy-reception?; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/10/acropolis-now-greeks-outraged-at-concreting-of-ancient-site?

MIchael Herzfeld, Cultural Intimacy.

Kinney, D. (1997). “Spolia. Damnatio and Renovatio Memoriae.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 42, pp. 117–148.

Lowenthal, D. (1985). The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge University Press,

Jan Assmann, Cultural Memory and Early Civilization

https://sanhs.org/wp-content/uploads/Stout.pdf

Herzfeld, Michael. Ours Once More: Folklore, Ideology, and the Making of Modern Greece. Princeton University Press, 1982; Galani-Moutafi, Vasiliki. “The Self and the Other: Traveller, Ethnographer, Tourist.” Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 27, no. 1, 2000, pp. 203–224.

Gourgouris, Stathis. Dream Nation: Enlightenment, Colonization, and the Institution of Modern Greece. Stanford University Press, 1996; Hall, Edith. Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy. Oxford University Press, 2008; Tziovas, Dimitris. Greece in Crisis: The Cultural Politics of Austerity. I.B. Tauris, 2017.

So interesting! I’ve lived in the states all my life and only have a small connection to it second hand by means of entering the Orthodox Church and spending the last 15 years reading about Greak saints and researching mostly late-antique Byzantine history, philosophy, and theology. I’ve come across some of the sort of East West divide in contemporary Greece largely through philosophers like Christos Yannaros and Greek theologians. In that field I sensed a battle between those swayed by a more “scientific”, scholastic western approach to theology, and those trying to hold onto an “eastern” phronema.

What really struck me though is how much I’ve seen us in the states essentially divorce ourselves from any real historical understanding or tradition—not really having our own—and the same is often occurring cross Europe. But if we can’t preserve the marks of history and value any tradition grounded in nothing more than our own rather spontaneous predilections, we seem to lose history itself. But how can we understand our selves without understanding history. It’s like Benjamin’s angel of history caught up in the winds of progress, and trying to bring back the dead, but ever drawn forward by false dreams of paradise. Only by seeing what’s behind us though can we even have an inkling of the consequences of our actions now and the reasons for them.

It reminded me of the debates we had here about how to rebuild Notre-Dame in Paris after the 2019 fire.

Anyway, please continue to resist "progress" and don't bring down the trees that obstruct the view!