Solomonic Magic and Astrology in Orthodox Tradition - and Modern Greece

Echoes of Aion and celestial timekeeping as Helios still reigns supreme

Please note that as a long read, not all of this post will show up in your inbox. Just click on the “read more” link at the bottom to see the full post, or click here to view the full post in your browser.

Η ουχί τοιούτος ο χρόνος ου το μεν παρελθόν ηφανίσθη, το δε μέλλον ούπω πάρεστι, το δε παρόν πριν ή γνωσθήναι διαδιδράσκει την αίσθησιν;

Or is time not such whose past is gone, whose future not yet apparent, and whose present escapes the senses before it is even known?

St Basileios [the Great], Hexaemeron1

I apologise to readers for the delay in posting this week; Easter is always a frenzied time in my home town of Corfu, with participation in communal rituals being one of the most intensely liminal parts of the year.

I considered writing these up in more detail, but was won over by the emphasis on ritual time during this period, leading me to develop this extended piece as this week’s offering. I felt it was time (pun inevitable!) to highlight the central role of ritual time and the planetary hours in continuing Greek ritual and practice.

Time and temporality are among the most fundamental elements that shape culture; how we perceive time shapes the way we perceive the cosmos, personal and collective identity, and matters of hegemony.

I have alluded repeatedly to the nature of cyclical time, its reliance on contact with nature, and its significance to the ritual year in Modern Greek reality: this is a pre-modern conceptual framework that has a great impact on the cultural perceptions and dynamics.

Without actively experiencing and consciously adopting it, it is very difficult to see how any experiential practice claiming to rest on Greek foundations can possibly remain true to its roots, still less to be its heir.2

In the Greek cultural matrix, and especially in the context of Orthodox theology, the ritual year is a circle, but it is also a spiral, for the cosmos is perceived to be in a state of perpetual unfolding and becoming.

The potential and urgency for human becoming is embedded within it, with the greatest driving force of all being that of free will and mindful eros. I will elaborate on this point at another time but I circle round to it at the end of this piece (the unintentional puns are going to keep coming and there’s nothing to be done!)

Here we unfold the continuous evolution and becoming of a living tradition with the celestial hours as points of reference for the invocation of personifications of the divine into sacred spaces, images, and participants.

The elements the West bundled into an “esoteric tradition” out of reinterpreted fragments ripped from their cultural substrate remained integral to a living tradition that was called Orthodox, but seems to have become a counter-culture beginning with the Schism. Most esoteric practices are not countercultural in Greek reality, but Orthodoxy is countercultural vis-a-vis the Latin and Lutheran West, and has found itself in the wastebasket of Western history more than esotericism ever did. At the threshold, Thyrathen, we explore its secrets hidden in plain sight.

This offering focuses on the very real survival of ancient timekeeping and cosmology - and its reliant magical, spiritual, and lay practices - throughout the Byzantine and modern periods. We may curse newer religions for displacing the old ones; but it is best to do so according to the facts, rather than the fiction.

Roots: Ptolemaios’ Tetrabiblos & “Almagest”

The second century Alexandrian astronomer and mathematician Claudios Ptolemaios codified Hellenistic (drawing on astrological and astronomical knowledge and practices in his magisterial four-volume Tetrabiblos (aka Apotelesmatika, meaning Effects), and the Mathematike (Megale) Syntaxis (known as the Almagest from the Arabic epithet Al-majisti).3

Written and transmitted in Greek as a synthesis of Babylonian, Egyptian, and Greek traditions, these exerted a profound influence on Byzantine intellectual culture from the 4th century on.4

Ptolemaic timekeeping

The Mathematike Syntaxis formalised the division of the day into two sets of twelve unequal hours based on the time of sunrise and sunset, and adjusted in every season. The Byzantine calendar divided the day into 24 hours from midnight, with the first diurnal hour at dawn, employing 12 unequal hours per day and night.

It is often incorrectly stated that this system ceased in the fifteenth century with the fall of Byzantium; however, it continued during the Ottoman occupation of Greece, dubbed “alla Turca” time (juxtaposed with alla Franga, or French time), both terms sometimes encountered in old manuscripts and in use until at least the 18th century.5 It remains the main timekeeping method used on Mt Athos, known as Byzantine time (juxtaposed with “secular” or “European” time).

Planetary Magic

Ptolemaios’ Tetrabiblos assigns celestial influences to temporal segments (ie, hours) which are the basis of many of the magical practices encoded in the Greek Magical Papyri. Rituals are timed to specific planetary influences, such as Mercury’s hour for communication (PGM IV.1596–1715) or planetary rulers for broader efficacy (PGM XIII.1–343).6 The temporal system precisely reflects Ptolemaic timekeeping and the attendant astrological traditions, overlaid with a syncretic integration of Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, and early Christian elements.

As a mode of division of time, the seven-day week derives from Jewish practices and is attested as early as the 5th century BCE; this repeating unit of time was not found among neighbouring cultures, but is first attested in the Septuagint (among Greek-speaking Jews), and was more widely adopted around the second century CE.

In Hellenised regions a planetary system also known as the Chaldean Order was applied for naming the weekdays : (Day of Kronos for Saturday; Helios for Sunday; Selene for Monday; Ares for Tuesday; Hermes for Wednesday; Zeus for Thursday; Aphrodite for Friday). Of these, Tuesday and Wednesday still echo in some Romance languages and even English (Mardi; Mercredi; Saturday, Sunday).

Early Greek-speaking Christians reverted to the Hebrew system, in which the days were not named, but simply numbered. Since Sunday was designated “Day of the Lord”, this was named Kyriaki, with the weekdays renamed numerically: Second (Deftera=Monday); Third (Triti=Tuesday), and so forth until Friday. In the Hebrew tradition, Friday was a day of preparation for the Sabbath, hence named Παρασκευή (meaning preparation in Greek), while Saturday (Σάββατον) is a loan-word from Hebrew reflecting the Sabbath.7 The planetary names for the days survived somewhat longer in southern Italy and Sicily, while the early Christian system was eventually adopted across the Byzantine Empire.8

The same system was used to calculate the creation of the world, adopted in 691 CE by the Quinisext Council under Justinian II, intending to replace the earlier “Alexandrian system,” which nevertheless remained in use among many clerics and monks.9 It is codified in the Paschalion Chronikon, a 628 universal history, according to which the world was created on the Spring Equinox of 5508 BCE. (Therefore 5508 is added to the current year to calculate the Etos Ktiseos - date since Creation).

This “Constantinopolitan" system was abandoned among the Orthodox laity in 1728, but is still used on Mt Athos. It differs from the Jewish calculation of time; though both use the genealogies of the Old Testament as a guide, the calculations differ.

Byzantine Hours: Secular and Liturgical Applications

In the Byzantine Empire, the planetary hour system was adapted to secular and liturgical contexts, with astrology flourishing in agrarian, lay, and court circles.

Educated laity consulted Ptolemaic manuals for auspicious timing in activities like agriculture, favoring Jupiter’s hour for prosperity.10 At court, Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) employed astrologers who implemented calculations derived from the Tetrabiblos to time military and diplomatic actions, such as treaties during Mercury’s hour. 11

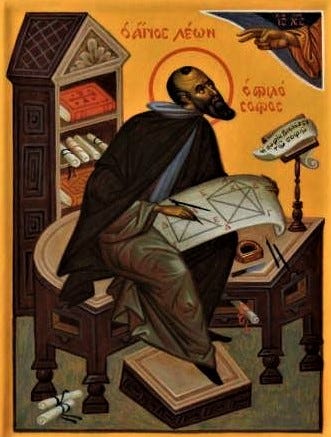

Scholars like Leon the Philosopher (790-p.869, also known as the Mathematician) preserved Ptolemaic texts, integrating astronomy into courtly scholarship.12 Raised in Andros where he was taught rhetoric, philosophy, and mathematics by monks, he later became the archbishop of Thessaloniki and teacher of Aristotelian logic at Magnaura School in Constantinople. Leon sought out and preserved all the extant work of other ancient thinkers, including Apollonios, Pergaieos, Theon of Alexandria, Archimedes, and wrote extensive commentaries on Euclid and Plato.

His work fostered a revival of classical learning and repositioned the Byzantine court as a hub of philosophical and scientific inquiry at the end of the second iconoclasm (a topic I will develop in due course). His Ptolemaic studies influenced later scholars and the transmission of texts like the Hygromanteia (on which more below).

Despite tensions with the ecclesiastic authorities that led to the loss of his archbishopric, he was popular with several emperors and other clergy. He invented a number of mechanical automata and the optical telegraph (fryktoria) based on a system of hourly hydraulic clocks (horonomion) and numerical codes. These transmitted news codified according to the hour when the beacons burned, so that important news could be transmitted across the empire within 11 hours.13

Several Byzantine chroniclers attest to his significance, yet very little of his writing survives aside from a few poems and his commentary on Euclid. This fragment is highly revealing of his spirit, degree of classical learning, and integration of faiths and worldviews (especially since the concept of Tyche - Fortune - was anathema to Orthodox theology which emphasised human free will):

Hail, Tyche (poem fragment by Leon the Philosopher)

Hail, Tyche, you do well to decorate me with the pleasant idleness of Epikouros

offering me comfort through peace.

What do I need with the business of men with many cares?

I do not desire riches, a blind, fickle friend,

nor honours, which are to mortals a faded dream;

Leave me, oh dark cave of Circe; I am ashamed,

though I have come from heaven, to eat acorns like a beast.

I hate the sweet food of the Lotus-eaters that makes one forsake one’s homeland.

And the tempting music of the Sirens I repulse as an enemy;

May I receive the godgiven, soul-saving flower,

Moly, the shield against evil thoughts; sealing my ears

well with wax I hope to pacify my sexual urges.

I wish to reach the end of my life saying and writing these things.14

Liturgy

The Byzantine hours were integral to the precise lunar and solar calculations needed for fixing the date of Easter and other movable feasts. Seventh-century monk Georgios emphasized their astronomical alignment for dating sacred events.15

Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos also informed liturgical texts like the Horologion, since prayers are scheduled to hours tied to celestial cycles (e.g., Third, Sixth Hours).16 The Orthodox overlay on these prayers emphasises spiritual discipline and reflects a temporal framework tied to the narrative of Christ’s life mapped upon the cosmic order.17

More than simply commemorating these events, in the Orthodox liturgy it recreates them through elaborate ritual that include invocations of the Trinity, specific angels and saints, and the use of designated incenses, harmonics and calls precisely as seen in “esoteric” workings. This recreation is vivid, intense, and for many, very powerful. See more on this in my earlier piece on the Voces magicae and their preservation in Orthodox chanting.

These incenses remain in production on Mt Athos following ancient recipes (and are commercially available directly from monastery outlets).

I do not believe this phenomenon has yet been properly examined in relation to other late antique practices based on sacred figure narratives (such as the reflection of Aion and the cosmic order); my own preliminary exploration of this reveals more than a few similarities. A proper, interdisciplinary scholarly comparison is sorely needed: and philological work alone does not suffice.

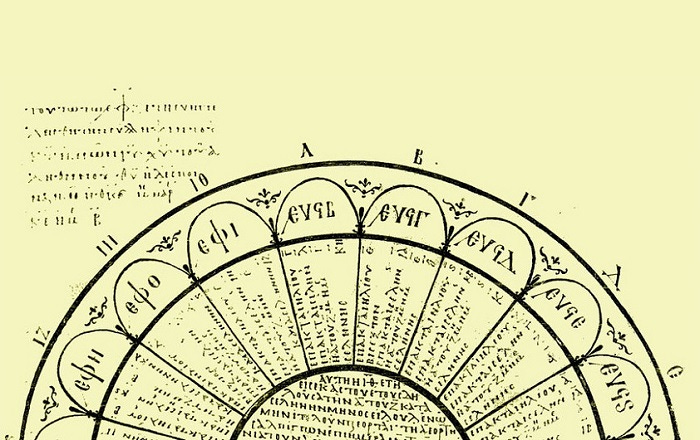

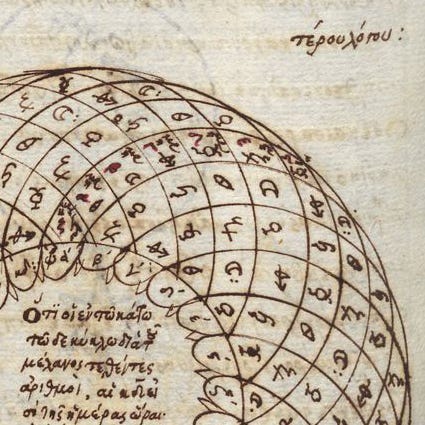

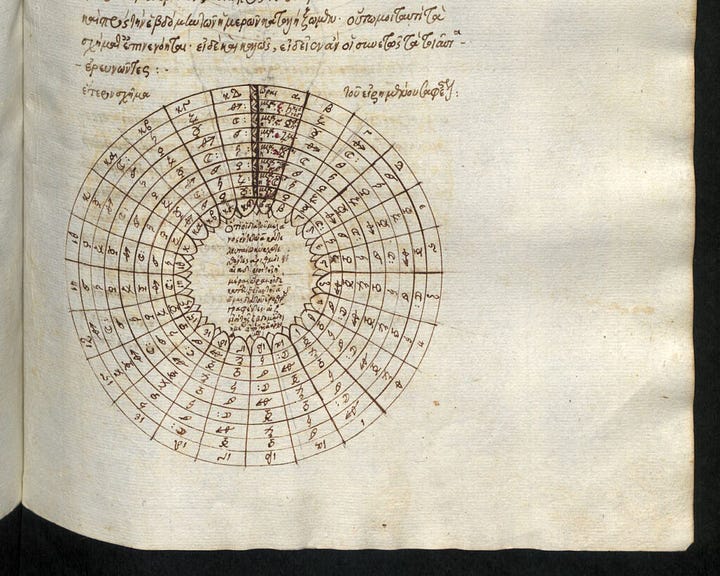

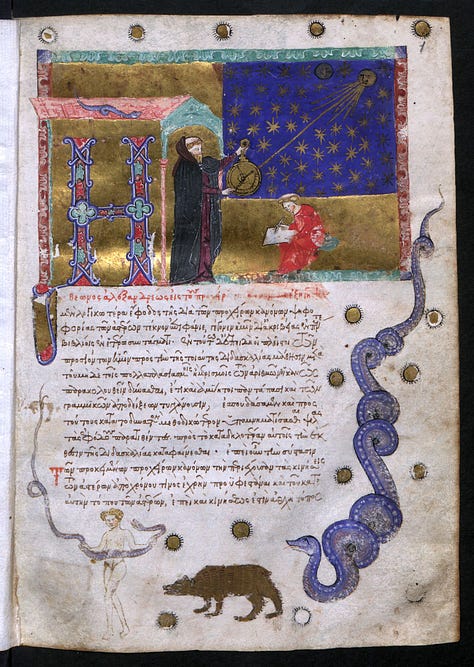

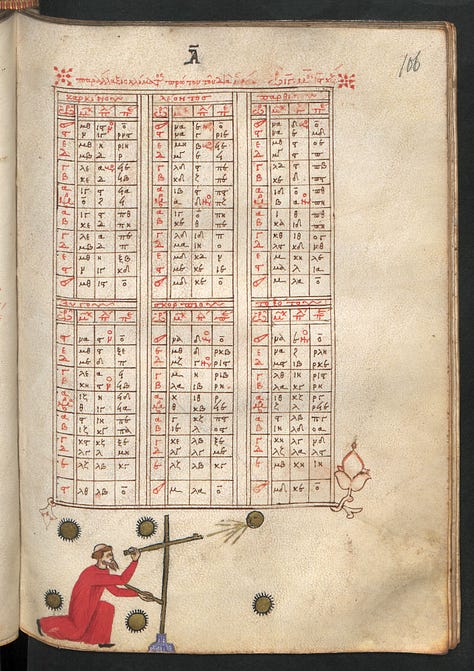

Manuscripts such as Ambrosiana C 263 (16th century) preserve Ptolemaic planetary hour tables, used in ecclesiastical astronomy to align the Orthodox liturgy with celestial phenomena.

Still others depict the lengths to which clerics went to correctly study and establish celestial movements in order to make their calculations; this was an active practice rather than a reliance on Ptolemy alone:

Solomonic Magic: Hygromanteia and Key of Solomon

The Hygromanteia, or Magical Treatise of Solomon, a medieval Greek grimoire, bridges the PGM and what became the Western esoteric “tradition”. Thought to have been composed in Byzantine southern Italy or Venetian Crete between the 6th and 14th centuries, it details rituals for talismans, spirit invocations, and divinations, timed to planetary hours.18 Its Mercury-hour rituals reflect PGM IV.1596–1715, indicating direct influence from the PGM’s Ptolemaic framework.19

The Hygromanteia adapts PGM practices to a Christian context, substituting pagan deities with angels and demons while retaining the planetary hours of the Tetrabiblos.20 It incorporates Jewish mysticism, including angelic names and kabbalistic symbols, possibly reflecting an influence from Byzantine Jewish communities in southern Italy.21

Byzantine demonology employed planetary hours for exorcisms, a practice rooted in PGM traditions, echoed in the Hygromanteia,22 as well as other folk grimoires and iatrosofic texts still in wide circulation. As noted in last week’s article, the preservation, development, and transmission of such texts was widely mediated by monasteries folk medics, and scholars.23 The Hygromanteia’s development was further fuelled by the prominence of Byzantine astrology in lay and court circles.24

The Key of Solomon is a Renaissance compilation of medieval sources that draws directly on Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos and Planetary Hypotheses. The grimoire’s reliance on the Hygromanteia is evident in shared planetary hour structures, angelic invocations, and Ptolemaic timing, adapted for a Western esoteric context.25

Though its influence is well-established, and its efficacy attested by its practitioners, the point I will continue to emphasise is that this represents a branch from a trunk which remains alive, with a solid conceptual, theological, and philosophical framework underpinning it. That requires a lot more unpacking, but I will close with just one key element.

Astrology in churches?

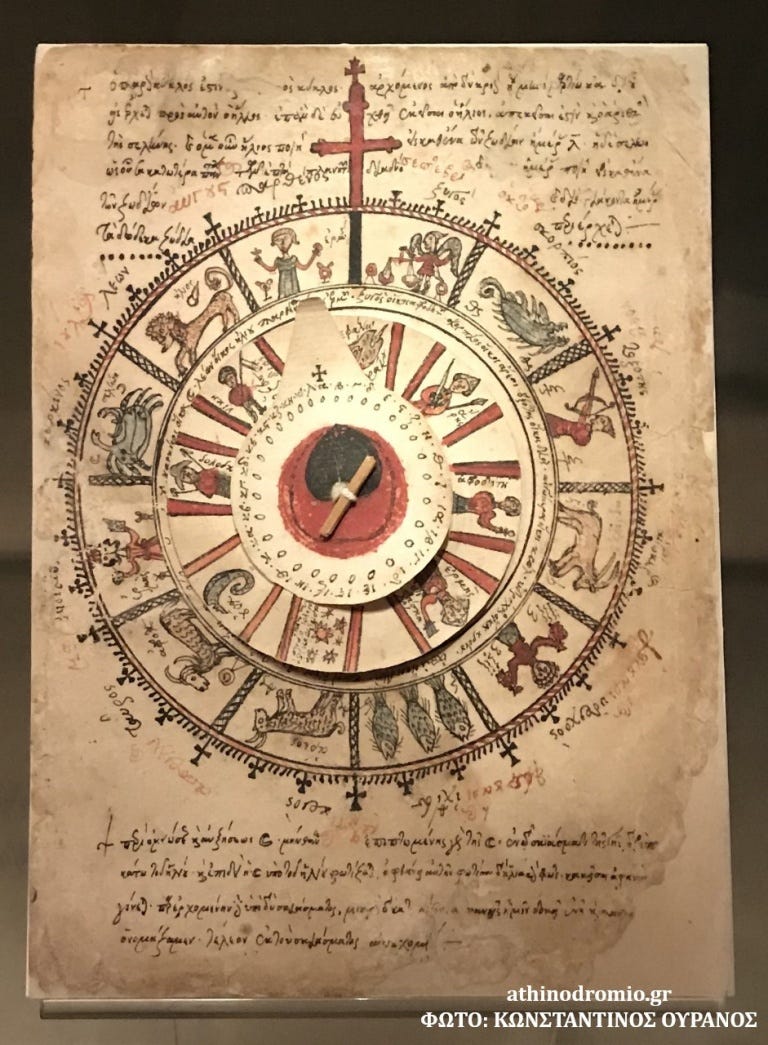

The circle of the Zodiac is seen in Byzantine manuscripts of the 14th century as well as in numerous frescoes in churches and monasteries across the former Byzantine lands. They became especially popular from the 17th century onwards.

The first icon-type shown here depicts the cosmic hierarchy and is labelled “In you rejoices, most gracious one, all creation, the system of angels and the race of humans.” The zodiac is mapped to angels and its significance explained as follows by St Nikodemos of Naxos (18th century):

Hail bright circle of twelve zodiacal signs, through which Christ the sun proceeded. And incarnated within the [divine] economy, for the salvation of humanity, fulfilling all of time.

Theotokarion of St. Nikodemos

The important 20th century iconographer Fotis Kontoglou explains its use in icons thus:

A rare depiction is the hagiography [depiction as saints] of the Sun and Moon, obviously symbolising the Most Holy Theotokos as outshining every constellation or planet through which Christ proceeded, himself an intelligible Sun for the salvation of Humanity.

The second fresco from the pronaos of the Church of the Heavenly Hosts in Milies is entitled “The vain life of the world of illusion.” The passage of the year is depicted by a wheel, encircled by the zodiac, each corresponding to a month, and enclosing the seasons personified by young (Spring), middle aged (summer, autumn), and elderly (winter) men. The elderly king in the centre depicts “the world of illusion.” At the top sits an earthly king holding a sword and a pouch of money, surrounded by seven male figures at various stages of life, from birth to death (it is reminiscent of Shakespeare’s seven Ages of Man, but it derives from Hippocrates)26. A strong young man is rising to push him from the throne.

The didactic purpose of the icon is obvious in relation to the vanity of youth, beauty, worldly riches and serves also as a memento mori. Yet it also reflects the infinite renewal of nature and life through the turning wheel of the year; the eternal return of the sun, moon, and seasons, and the emphasis on the generation of new life through the personified seasons: life and the promise of regeneration is hidden within matter itself.

A key reason for which the Orthodox doctrine condemns predictive astrology is down to the theology of the nature of humanity: the concept of preordained fate is considered utterly unacceptable, as humanity has been granted the gift of perpetual becoming, if they grasp it. Since personal and predictive horoscopes imply preordination, this conflicts with the doctrine of free will. Hence, though the zodiacs are seen as governing the seasons and as part of material nature, they can never impact the soul. This element deserves broader discussion that I hope to get to in time (sorry!), but for now, may provide fruitful food for thought (sorry again!)…

These perceptions of time are how we live, work, and even the secular, participate in communal ritual to this day. Have you considered how the perception of time in your own cultural matrix informs your conceptualisation of such matters? Let me know in the comments!

The promised translations for paid subscribers will be published this Sunday. Thank you from the heart for your support, it is both valued and needed, and I am rearranging my post scheduling just a little to begin producing more material for paid subscribers alone to express my gratitude.

Please remember that Thyrathen is a reader-supported publication; I believe you can see how much work goes into every piece. Please do consider supporting however you can. I’ve decided to keep feature articles free, but will be producing more specialised material for paid subscribers only, and am considering a live communication channel to engage with you all more closely. Please do let me know if there are specific topic or other requests that might be of interest!

Enjoy the free content but currently unable to subscribe?

Hexaemeron: A 4th century collection of nine homilies given by St. Basileios in Caesaria on the nature of Genesis I and the creation of the world in six days, reflecting a fusion of Greek Neoplatonic thought with early Christian theology precisely at its inception. Though the term was used by Philon of Alexandria in his own allegorical reading of Genesis, that of Basilieios is the earliest Christian Hexaemeron (a genre in itself focused on biblical commentary that overlaps with the pagan tradition of philosophical treatises on the origins of the cosmos) that strongly influenced other Orthodox and Latin theologians. See Kochańczyk-Bonińska, Karolina (2016). "The Concept Of The Cosmos According To Basil The Great's On The Hexaemeron". Despite the problematic translation from Polish, this writeup is a close reading and summary of core elements of Basileios’ Hexaemeron.

https://www.rhuthmos.eu/IMG/pdf/gonzalo_iparraguirre_time_temporality_and_cultural_rhythmics.pdf; https://www.academia.edu/5968780/Cultural_Mismatches_Greek_Concepts_of_Time_Personal_Identity_and_Authority_in_the_Context_of_Europe_in_Kevin_Featherstone_ed_Europe_in_Modern_Greek_History_Hurst_and_Co

Claudius Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos, trans. F. E. Robbins (Harvard University Press, 1940), Book I, Chapter 8, 83–85; Claudius Ptolemy, Almagest, trans. G. J. Toomer (Princeton University Press, 1998), 1–3; 68–70; Maria Mavroudi, “Occult Science and Society in Byzantium,” The Occult Sciences in Byzantium (La Pomme d’Or, 2006), 89–90. The Mathematike Syntaxis (Almagest) provides the mathematical and astronomical foundation for the Tetrabiblos’ astrological applications.

Francesca Rochberg, “Babylonian Horoscopy: The Texts and Their Relations,” In the Path of the Moon (Brill, 2010), 45–47.

1. Tunçalp D. Times Alla Turca E Franga: Conceptions of Time and the Materiality of the Late-Ottoman Clock Towers. In: de Vaujany F-X, Holt R, Grandazzi A, eds. Organization as Time: Technology, Power and Politics. Cambridge University Press; 2023:297-328.

Hans Dieter Betz, ed., The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells (University of Chicago Press, 1992), xlvi, 62–65, 172–175.

Some scholarly sources simply note that “rejecting pagan Latin day names, Byzantines used terms like Kyriake (Lord’s Day) and numbered days (Deutera, Trite), reflecting Roman influences Christianized for ecclesiastical use. [Marcus Rautman, Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire (Greenwood Press, 2006), 45.] Yet the Jewish influence - indeed the very significant Jewish content of Orthodox practice and liturgy should be paid far closer attention. There was no concept of a seven-day week among Greeks and Romans until the period in question, nor can we really speak of Byzantines in the second-third century Middle East since this practice derived from Greek-speaking early Christians of both Jewish and mixed pagan origins. It is sweeping generalisations such as this that have created a false image of a monolithic “Byzantium” with cut-off points in time that simply do not apply.

Dennis H. Green, Language and History in the Early Germanic World (Cambridge 1998), 236-253.

Βασιλικοπούλου-Ιωαννίδου Αγνή, Η Βυζαντινή Ιστοριογραφία (324-1204)-Σύντομη Επισκόπηση, Αθήνα 1982, σελ. 48.49.

Maria Mavroudi, “Occult Science and Society in Byzantium: Considerations for Future Research,” The Occult Sciences in Byzantium, ed. Paul Magdalino and Maria Mavroudi (La Pomme d’Or, 2006), 81–82, 85.

Paul Magdalino, “The Byzantine Reception of Classical Astrology,” Literacy, Education and Manuscript Transmission in Byzantium and Beyond, ed. Catherine Holmes and Judith Waring (Brill, 2002), 36–38; Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos, Book III, Chapter 4, 267.

Mavroudi, “Occult Science,” 89–90.

Tougher, Shaun (1997). The Reign of Leo VI (886–912): Politics and People. Leiden: Brill. p. 113; Treadgold, Warren T. (1979). "The Revival of Byzantine Learning and the Revival of the Byzantine State". The American Historical Review. 84 (5). American Historical Association: 1245–1266; Leone Montagnini (2002), "Leone il Matematico, un anello mancante nella storia della scienza", Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Studi sull'Oriente Cristiano, 6 (2), 89–108. Efthymios Nicolaidis (Susan Emanuel trans.) ‘Science and Eastern Orthodoxy: From the Greek Fathers to the Age of Globalization (Medicine, Science, and Religion in Historical Context)’, Νοv.8.2011.

Palatine Anthology XV 12 (Kaktos Publishing, Athens). Translation mine.

Εὖγε, Τύχη, με ποεῖς ἀπραγμοσύνῃ μ᾿ Ἐπικούρου

ἡδίστη κομέουσα καὶ ἡσυχίῃ τέρπουσα.

Τίπτε δέ μοι χρέος ἀσχολίης πολυκηδέος ἀνδρῶν;

Οὐκ ἐθέλω πλοῦτον, τυφλὸν φίλον, ἀλλοπρόσαλλον,

Οὐ τιμάς· τιμαὶ δὲ βροτῶν ἀμενητὸς ὄνειρος·

ἔρρε μοι, ὦ Κίρκης δνοφερὸν σπέος· αἰδέομαι γὰρ

οὐράνιος γεγαὼς βαλάνους ἅτε θηρίον ἔσθειν·

μισῶ Λωτοφάγων γλυκερὴν λιποόπατριν ἐδωδήν,

Σειρήνων τε μέλος καταγωγὸν ἀναίνομαι ἐχθρῶν·

ἀλλὰ λαβεῖν θεόθεν ψυχοσσόον εὔχομαι ἄνθος,

μῶλυ, κακῶν δοξῶν ἀλκτήριον· ὦτα δὲ κηρῷ

ἀσφαλέως κλείσας προσφυγὴν γενετήσιον ὁρμήν.

Ταῦτα λέγων τε γράφων τε πέρας βιότοιο κιχείην.

Marcus Rautman, Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire (Greenwood Press, 2006), 47. For the Paschal Chronicle: 1. Neville L. Paschal Chronicle. In: Guide to Byzantine Historical Writing. Cambridge University Press; 2018:52-55.

Darin Hayton, “Byzantine Tables of Planetary Hours,” Darin Hayton, 22 Jan. 2021, dhayton.haverford.edu/byzantine-tables-of-planetary-hours/.

Holy Transfiguration Monastery, The Great Horologion (Boston: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 1997), 1–5.

Pablo A. Torijano, Solomon, the Esoteric King: From King to Magus, Development of a Tradition (Brill, 2002), 156–158; Ioannis Marathakis, trans., The Magical Treatise of Solomon, or Hygromanteia, ed. Stephen Skinner (Golden Hoard Press, 2011), 23–25.

Betz, Greek Magical Papyri, 62–65; Marathakis, Hygromanteia, 89.

Marathakis, Hygromanteia, 45–47; Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos, Book I, Chapter 8, 83–85.

Katelyn Mesler, “The Transmission of Jewish Magical Texts in Medieval Europe,” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 9, no. 2 (2014): 127–130.

Richard P. Greenfield, Traditions of Belief in Late Byzantine Demonology (Hakkert, 1988), 112–115.

David Pingree, “The Diffusion of Arabic Magical Texts in Europe,” The Legacy of Muslim Spain, ed. Salma Khadra Jayyusi (Brill, 1980), 60–62.

Mavroudi, “Occult Science,” 92.

Torijano, Solomon, 156–158.

Clerical attitudes to astrology are an interesting subject in their own right. The idea that astrology is impermissible because it can't be reconciled with free will came to be held in the Catholic West too. This still left room for predicting things that weren't dependent on free will, such as a person's health. It was also believed that it was acceptable to predict the behaviour of *large numbers* of people through astrology because, while each individual among them had free will, it was reasonable to say that general patterns of behaviour would assert themselves across a population. So, for example, you could use a horoscope to predict whether a nation would launch a rebellion. You could also use a birth chart to make *broad conjectures* about a person's actions, as long as you didn't claim that they were definite predictions. This is all a classic example of the pedantry of Catholic moral theology, and it would be interesting to know if Orthodox clerics descended into this level of hairsplitting.

Thanks for this. I believe the numbering system for days is also employed in Portuguese, a break from the other Latin languages.

That sense of spirality suggests the unfolding of Logos, his continual disclosure in time and space.

Are there any correspondences or resonances here for, say, the Liturgy of the Hours? Thanks again.