What We Keep Getting Wrong about Herakles

On the perils of reading ancient myth through modern eyes

Archaeologists, poets, and geologists all meet in the story of Herakles—but somewhere along the way, we forgot what he was really wrestling. But first, some housekeeping.

Housekeeping

I must apologise to my readers for this delayed post and the inconsistent schedule of the last couple of weeks. As many of you know, I have been in Berlin for the Occulture 2025 conference, where I delivered a well-received lecture on Modern Greek Goeteia. The slides and supporting material are available here.

Today is an opportunity to share with you a little insider perspective on how scholars approach material.

This is a free post for all readers by way of apology for the disrupted schedule, and includes an exclusive, full length video lecture from my Introduction to Hesiod course (see below). Read on for more.

About today’s post

Every culture remakes Herakles in its own image. To the ancients he was the man who wrestled nature into order; to us he’s a mirror for whatever we fear or admire about strength. What gets lost in that exchange is the prehistoric grammar that shaped him.

Recently, a casual remark I made online that “Herakles myths date from the Neolithic” was misunderstood, and additional evidence requested.

What follows lifts the curtain on why I insist on a particular approach to myth, how I do and don’t approach it, and why scholarship is the darkest of arts. I also hope to demonstrate the nature of scholarly responsibility wherever, and whenever, we write anything on record.

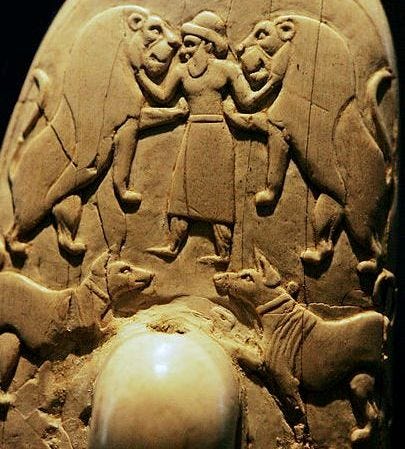

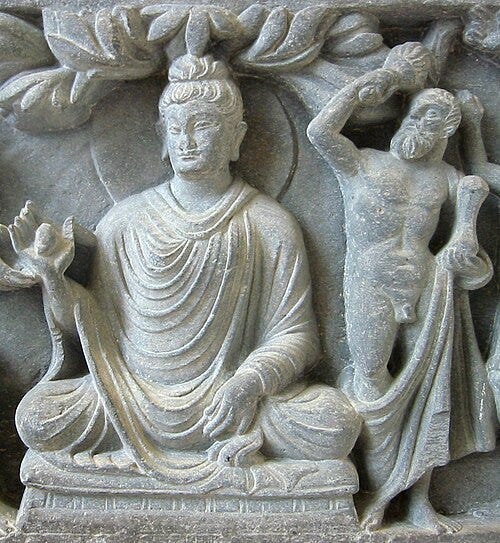

The symbolic complex that crystallises as Herakles draws on very old imagery and narrative grammar. Walter Burkert identified Herakles as the Greek crystallisation of the prehistoric Master of Animals type and traced its deep iconographic pedigree across the Near East and the Aegean.

Motif age is not Myth Age

The term prehistoric is used here in its archaeological sense: referring to material and iconographic evidence from periods before written records, not to cultural or ethnic continuity. In Mediterranean archaeology, prehistoric conventionally covers Neolithic through Bronze-Age horizons, and thus denotes the time-depth of certain symbols rather than of named figures or myths.1

In this context, “prehistoric” is not a claim about descent or ownership but a descriptor of archaeological time-depth. It marks the horizon where certain symbolic patterns first appear in material form, long before they are fixed in the narratives we later recognise as Greek myth.

Prehistoric here denotes the age of the motif, not the date of the Greek myth.

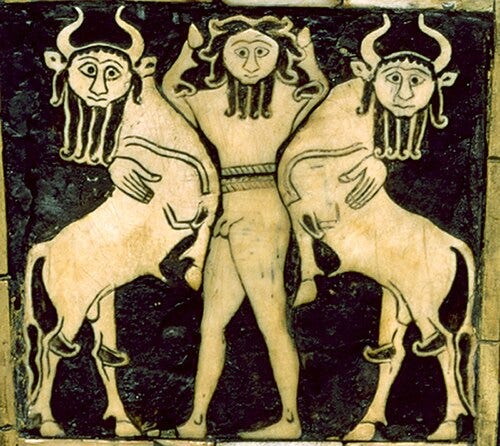

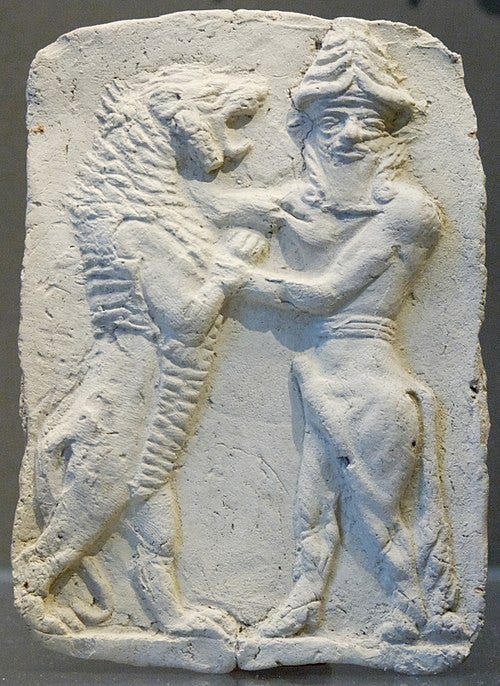

By “Master of Animals,” Burkert meant a very ancient visual schema: a central figure grasping or overpowering flanking beasts in symmetrical composition. This pattern appears in Neolithic and Bronze Age seals and figurines from Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Aegean.

He treated it not as a single figure passed intact through time, but as a symbolic grammar expressing the mastery of wild nature and the transformation of violence into order, first through the hunt and sacrifice, later through heroic narrative. This mirrors the Hesiodic epic narrating the adoption of Olympian order that subdues older, chthonic forces, a reading that is also well-documented.2

Burkert’s interpretation of Herakles as the Greek synthesis of a prehistoric “animal-subduer” type has not been superseded; only the explanatory framework has evolved. The idea of a Neolithic-to-Bronze-Age symbolic horizon feeding into the first-millennium Herakles remains accepted, though now framed in terms of shared iconographic grammar and multidirectional exchange rather than linear descent.3

Burkert did not claim an unbroken line from the Neolithic to classical Greece, and nor did I. Rather, he proposed a long process of exchange, adaptation, and recombination across the Eastern Mediterranean. Regular readers know that I consistently use the term “entanglement,” and “hybridity” belonging to recent research on transcultural and transreligious forms of ritual, to emphasise that there is nothing “pure” under the sun. 4

For avoidance of any doubt, readers are asked to familiarise themselves with my position statement on this here. Note that the scholarly version is below the lay summary:

What I meant by “Neolithic”

My remark that Herakles “dates from the Neolithic,”referred to the age of the Master-of-Animals motif that underlies the later mythic figure. In the sense used within the field this is indeed supported by “scholarly consensus.”

The prehistoric (Neolithic–Bronze Age) horizon of the motif is firmly established archaeologically and has been accepted since Burkert’s Homo Necans. Subsequent studies: West (1997), Larson (2007), Bremmer (2008), Stafford (2012), Thomas (2020), and Shapland (2025) all affirm that Herakles crystallises this older symbolic complex while updating Burkert’s diffusion model into a framework of networked exchange. I am not aware of any peer-reviewed work that denies the prehistoric time-depth of the imagery; debates concern mechanisms of transmission, not whether the motif precedes the literary figure.

The journey of a motif

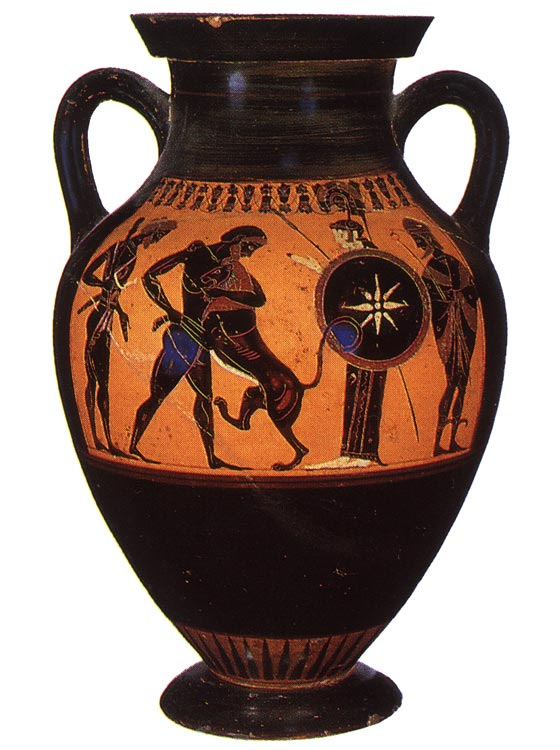

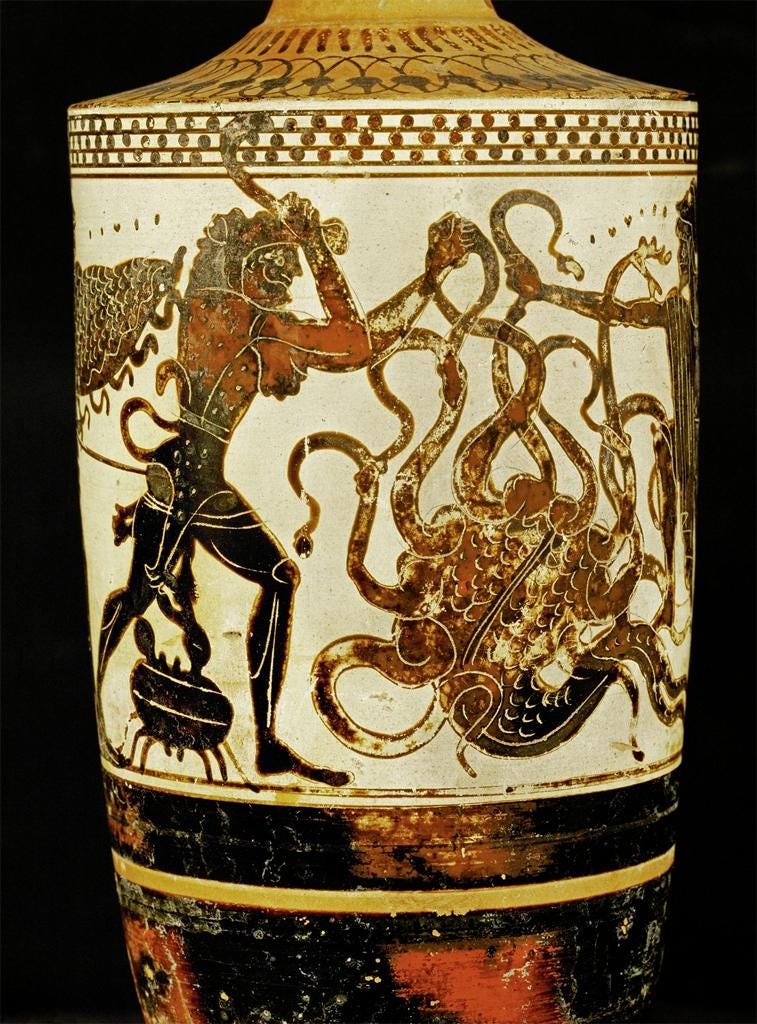

In Greek myth, the Labours of Herakles—lion, bull, boar, serpent, monstrous cattle—replay the symbolic patterns Burkert identified in narrative form. The hero’s feats mark the points where wilderness is subdued and made safe for human and civic life, a transition remembered in cult and visual art.

Shared motifs travelled through trade, craftsmanship, and ritual contact; local communities reinterpreted them; and Greek poets and artists eventually wove multiple strongman and beast-subduer strands into the capacious figure of Herakles. The motif may therefore be prehistoric, while the familiar Greek form of the myth, the Herakles we meet in literature and cult, is traced to the first millennium BCE.

My remark referred to the age of those older symbolic layers, not to the date of the written myths themselves. Herakles belongs to a mythic and ritual imagination whose roots lie in a worldview that predates our moral categories and social concerns by thousands of years. To evaluate this figure according to modern considerations of gender and behaviour is therefore not interpretation but a category error in historical terms, a point to which I return below.

This is neither a niche view nor a controversial one. It should be self-evident that we cannot map modern sensibilities onto the value systems of earlier eras or different cultures and still be fair to the material in question.

There is broad interdisciplinary agreement on the qualified claim that the Heraklean cycle synthesises prehistoric symbolic material. Scholars of Greek myth still recognise the link between Herakles and the ancient “Master of Animals” figure; what they now debate is how those older images and stories diffused into and through Greek tradition. 5

Archaeologists continue to map the type across iconography from prehistoric horizons into the Aegean. Geologists and Earth-science researchers have likewise developed geomythology, a field that studies how ancient stories preserve memories of real geological events such as earthquakes, floods, or volcanic eruptions. In that research, the stories about Herakles are often cited as examples, since several of his Labours appear to echo prehistoric features of the Greek landscape.

When the landscape speaks

A second, independent line of evidence comes from this field. In the Greek material, several episodes in the Heraklean cycle, particularly those involving rivers, caves, and the reshaping of terrain, appear to preserve memories of real prehistoric changes in the Aegean landscape. This body of work is represented in public lectures and in peer-reviewed venues such as the Geological Society of London Special Publications and the Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece.

H. D. Mariolakos has presented the Heraklean material extensively, and Elena P. Mitropetrou’s University of Patras PhD6 systematises these findings within a Greek framework of geomythology. Read together with the Master of Animals linkage and with contemporary network models of transmission, the claim aligns with both current classical and archaeological scholarship: the Heraklean cycle is an early Greek synthesis that recombines much older symbolic and environmental imaginaries, some traceable to prehistoric contexts.

Some further examples of such geomythological work are as follows:

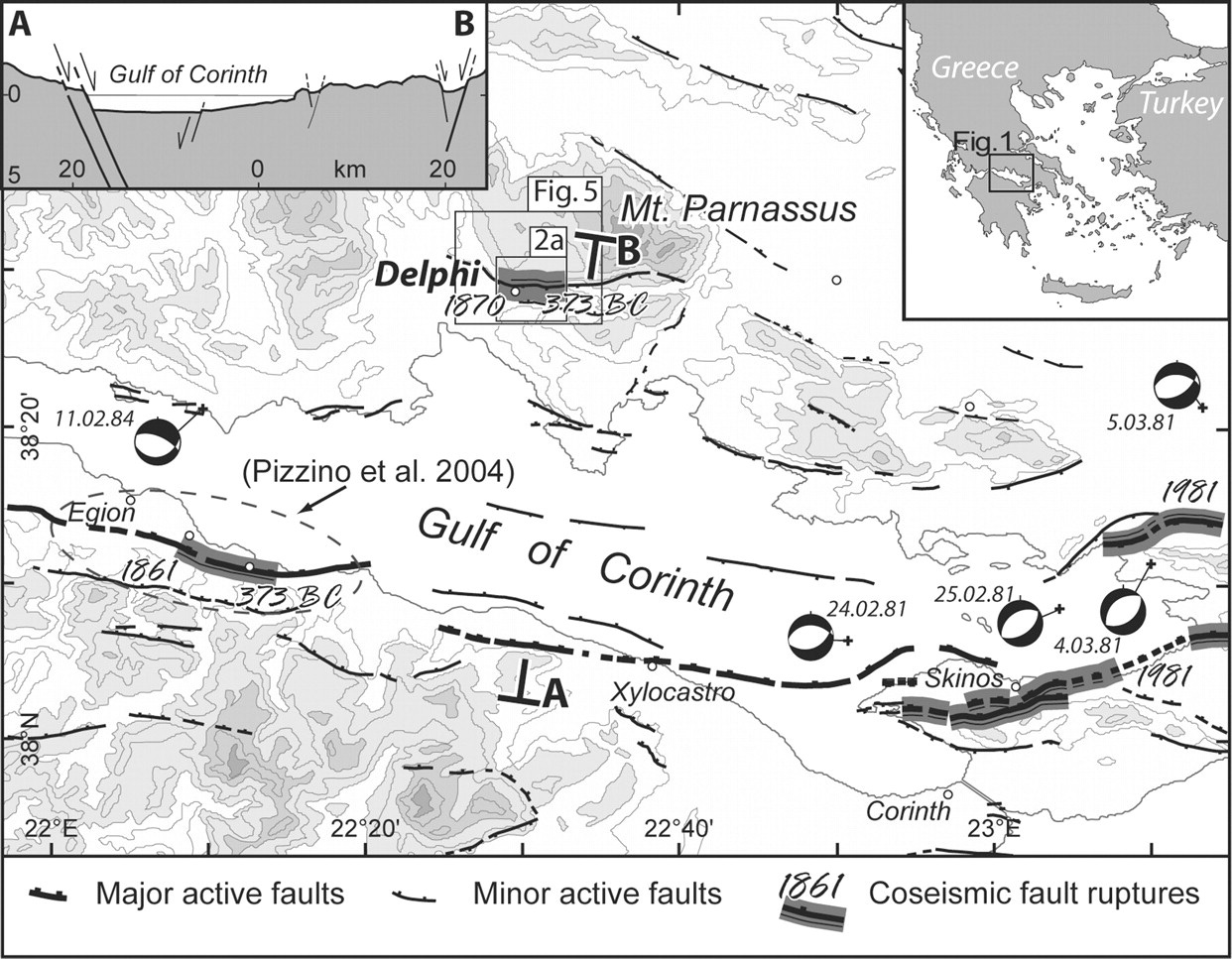

Delphi (oracle gases, faulting, and myth):

Piccardi et al. (above) show that ancient testimonies about vapours and a chasm at Delphi align with local fault intersections and episodic gas release; a flagship, peer-reviewed case of geological process preserved in Greek sacred narrative. 7Delphi (independent corroboration):

De Boer, Hale & Chanton in Geology locate young faults and explain water/gas pathways beneath the Temple of Apollo, reinforcing the geological basis behind the mythic-ritual setting. 8Greek palaeotsunamis (Aegean, multiple coasts):

Kortekaas et al. synthesise geological and geomorphological evidence for ancient tsunamis around Greece (sediment cores, boulder fields), providing the processual backdrop for flood/destruction narratives used in Greek mythic memory. 9Aegean prehistory tsunamis (Minoan, Troy):

Papadopoulos documents large prehistoric Aegean tsunamis and models impact supplying the event-layer that geomythology connects to narrative traditions. 10Greek tsunami deposits and historical correlation:

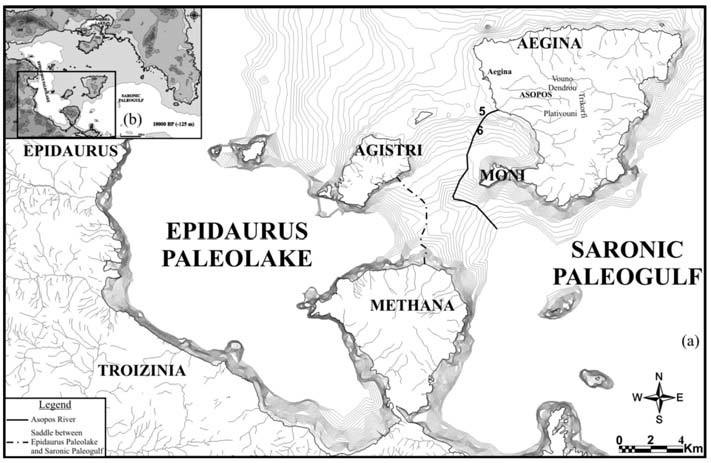

Papadopoulos et al. correlate trench stratigraphy with historically attested tsunamis from the eastern Hellenic Arc, showing how extreme events leave durable signatures that can underpin long-lived stories. 11Asopos/Aegina (river-island geomyth):

Mariolakos’ study in the Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece tests whether the Asopos river course and Saronic palaeogeography underlie mythic accounts, illustrating a method for linking local myths to palaeolandscapes. 12

From I. Mariolakos’ study on the Asopos river demonstrating how paleogeography applied alongside archaeology can contribute to the understanding of myth. Source. Greek geomythology overview in BGSG and elsewhere:

Mariolakos, The Geoenvironmental Dimension of Greek Mythology (BGSG), lays out a programmatic, peer-reviewed survey of Greek cases (rivers, islands, hazards) and their geological plausibility as sites of mythic narrative. 13Disaster geoarchaeology with Greek cases:

Liritzis integrates Greek archaeology, geology, and myth to show how catastrophic events become encoded as durable cultural narratives.14

These studies do not claim one-to-one event matching in every case; they propose geologically plausible contexts for enduring narrative patterns, especially where archaeology provides supporting data.

So where’s the problem?

The methodological issue is not semantic but structural. For over a century, the discipline of Classics has privileged philology and close reading of texts while marginalising material, environmental, and cognitive evidence that fall outside its traditional boundaries.

The result has often been a closed evidential loop that reproduces itself through commentary rather than enquiry. This is one of my core criticisms of the whole discipline that I have repeatedly highlighted along with the problems caused by disciplinary boundaries and the blind spots they create. At its best, philology is indispensable; but it simply cannot do the whole job alone. As an interdisciplinary specialist (my actual formal title), I zero in on these as part of what I do.

Efforts at innovative approaches sometimes attempt wholly new treatments that in and of themselves can be creative and insightful, but also distortive without appropriate framing.

As Burkert himself observed, philology can preserve evidence but cannot explain cultural function, for which context is crucial: “philology depends on a biologically, psychologically, and sociologically determined environment and tradition to provide its basis for understanding.” Textual exegesis must be joined with anthropology and ritual study if we wish to understand Greek myth as lived experience.15

Since the 1980s, archaeological and anthropological work has repeatedly demonstrated that literary texts are late surfaces of much deeper cultural processes. Excavation and iconographic study have traced mythic imagery back into prehistoric strata that philology alone cannot access.16 Cognitive and environmental approaches have shown that myth-making arises in constant interaction with landscape, resource use, and perception of natural hazard.17

When modern readings treat ancient texts only as self-contained pieces of literature, they cut those works off from the wider world that gave them meaning. In turn, this obscures those worlds to us. Interdisciplinary research restores that connection by drawing on archaeology, art, and the sciences to show how myth operated within lived experience. The Heraklean material makes this clear.

The “Master of Animals” imagery, the pattern of the Labours, and the hero’s confrontations with elemental or geological forces all appear first in material forms—seal stones, vase paintings, local cults, and oral traditions—long before they reach written versions.

Skimming the surface is bad scholarship

To study any text without that background is like trying to understand a palimpsest by reading only the top layer and ignoring the older writing beneath it, the age and provenance of the parchment, and the changing scripts through which it passed. This is the core limitation of a purely philological approach to myth, one that can be easily corrected through proper framing, discussed below.

A narrow focus on language or literary theory cannot explain why certain myths endure or how they evolve. It can describe style and rhetoric, but not the deeper cultural mechanics at work. The combined evidence from archaeology, geology, and comparative anthropology shows that Heraklean themes act as a thread connecting Neolithic ritual imagination (justified by the regional diffusion of the myth), Bronze Age imagery, and later classical storytelling. Bringing these fields together puts the philology back in context, allowing the texts to speak within the full complexity of their world.

And that, ultimately, is the point. If our aim is to understand the ancient world, we have to approach it on its own terms: through the full range of evidence that its people left behind. Without that, we are not studying antiquity at all, but merely using it as a mirror for ourselves. The task of the responsible scholar is to reconstruct how those societies thought, imagined, and represented their realities, not to conscript their stories into our own debates.

On framing and disciplinary limits

Modern interpretations can take many forms: psychological, political, gender-based, or symbolic, and in principle there is nothing wrong with that. But such approaches are only responsible when they are presented for what they are: modern readings, shaped by today’s questions and values. That means being transparent about the lens being used (for instance, a gender-critical perspective), what kind of evidence it draws on, and how far its conclusions can reach.

Without that framing, it becomes easy for a twenty-first-century critique to be mistaken for a statement about what the ancient Greeks themselves believed. We are still dealing with monumental errors made in older scholarship, where the beliefs and values of a particular time and place were overlaid onto historical material, leading to persistent misinterpretations.

Greatest hits of misreading

Victorian moralising of Greek religion

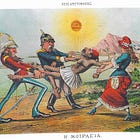

Early classicists such as L.R. Farnell and Jane Harrison framed Greek ritual as a primitive prelude to modern ethics or Christianity. They treated myth as an allegory of moral progress rather than a living religious system. This reflected Victorian confidence in “civilisational evolution” rather than ancient realities.18Racialist readings of Greek origins

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, scholars such as Friedrich Max Müller and Martin Nilsson tried to trace Greek culture to Indo-European or “Aryan” racial stock, interpreting similarities in myth as proof of biological descent rather than cultural exchange. Modern archaeology and comparative anthropology have dismantled those assumptions.19Gender and psychology projected onto myth

Mid-twentieth-century interpretations often read myths through Freudian or Jungian psychology, turning ancient figures into case studies of modern Western identity. For example, Medea was cast as a symbol of repressed hysteria or “female pathology,” while Dionysos became a metaphor for unconscious desire. Such readings said more about twentieth-century anxieties than about ancient religion.20The erasure of Byzantium

Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788) dismissed a thousand years of Greek-speaking civilisation as an age of “monks and sophists,” corrupt and degenerate in contrast to the rational heroism of pagan Rome. That caricature entrenched Western prejudice against the Eastern Roman and Orthodox world, cutting Byzantium out of the European historical imagination for more than two centuries. The damage was not only reputational but methodological: by deciding in advance what counted as “civilised,” scholars systematically excluded evidence that contradicted their own ideals.

A sequence of other approaches I have outlined elsewhere:

Each of these approaches distorted the evidence and reshaped public understanding for generations. They created hierarchies of “civilised” versus “primitive” belief, cemented racial categories that still haunt classical studies and public understanding, and encouraged the view that myth was a symptom of irrationality rather than a vehicle of meaning. The fallout extended well beyond academia: school curricula, museum displays, and popular retellings all carried those biases forward, teaching audiences to see antiquity through Victorian moral lenses or twentieth-century racial pseudoscience.

There is no excuse, in modern scholarship, for this to continue. To understand the ancient world—or any world not our own—we have to let it speak in its own categories, with the full range of tools now available to us.

Herakles will not sit still

In the case of Herakles, the ancient evidence is vast and contradictory. Different authors and artists portrayed him in different ways: as monster-killer, civiliser, servant, protector, even victim. There is no single, consistent model of “Greek masculinity” here, only a series of shifting, context-specific ideals. Works like Emma Stafford’s Herakles21 map this range across visual and literary evidence precisely to avoid reduction to one modern label.

One example often singled out is Sophokles’ Trachiniae. It is sometimes read today as a story about male pride or violent behaviour, but that misses the play’s complexity. Sophokles presents Herakles at a point of collapse between human suffering and divine transformation, between domestic life, fame, and impending deification. As it stands, this play in particular has been incisively explored by multiple scholars, with the sensible understanding that plays written for Athenian audiences reflected the concerns of those audiences in their time. Attempting to read it without first acknowledging this makes any attempt questionable.

The tragedy explores the contradictions of heroism rather than prescribing a moral lesson about masculinity. Scholars have long recognised that the play is not a behavioural case study but a meditation on conflicting values within ancient Greek culture itself.22 I have written extensively on this plurality of voice precisely to counter monolithic claims that automatically misrepresent the material:

Claims that Herakles is an archetype of “toxic masculinity,” let alone intimations that he speaks for Greek masculinity overall, fail on both counts. Greek masculinities were plural and situational, negotiated through civic, agonistic, domestic, and ritual contexts under differing norms. The standard studies: Rosen and Sluiter’s Andreia23 and Foxhall and Salmon’s When Men Were Men (1999) show manliness as a contested cultural value that varies by genre, occasion, and community. The Oxford Handbook of Heracles likewise proceeds by discrete case studies demonstrating the hero’s local recompositions rather than a monolithic essence. A responsible reading situates any modern critique within that evidential ecology. All it takes is one line, but that line makes the difference.24

Accordingly, a responsible approach to contemporary interpretations, even when published in informal and semi-formal venues, is clear:

Declare the lens and scope up front: state that the reading is a modern critical intervention, not a reconstruction of historical Greek norms. Do not allow the reading to stand in for an authoritative historical claim.

Cite the evidential hierarchy: acknowledge the variability of Herakles across sources and periods and the specific context of every source.

Avoid totalising inferences: do not let one reading or one disciplinary tool suggest that the reading is definitive; anchor any generalisation in the broader scholarship.

Cross-check with the broader Heraklean mythos: use handbooks and surveys to test whether the proposed traits hold across evidence or are contextual effects.

Above all, check one’s own positionality and factor it into the reading.

Framed this way, modern or “new-school” readings can be productive, innovative, and creative. Unframed, they overclaim and misinform the public. A discipline that relies solely on philology and literary theory is no longer adequate to the material, environmental, and comparative evidence now available. Texts live within those contexts, which often correct or enlarge what close reading alone can see. The Heraklean corpus makes that visible: it is a palimpsest of prehistoric symbols, local cults, and later literary transformations. To read it responsibly requires interdisciplinary literacy, not moral projection.

On cultural responsibility and the consequences of omission

When framing is omitted, the cost is not just intellectual precision but scholarly integrity, because the material under discussion is turned into a stage for rehearsal of whatever theory one applies. Unframed performances that treat ancient figures as direct stand-ins for modern archetypes—whether moral, political, or psychological—produce distorted narratives that migrate rapidly beyond the academy.

Within the compressed, viral economy of the internet, a complex cultural phenomenon becomes reduced to slogans: “the Greeks fostered toxic masculinity,” “Herakles is the first misogynist,” “Medusa and Persephone were victims of rape culture,” “all Greek women were oppressed,” “Hera was a jealous misery-guts,” and the ubiquitous Nietzschean Apollo-Dionysus binary. These are not readings; they are soundbites. They erase context, flatten historical diversity, and feed a wider culture of disinformation that substitutes outrage for understanding.

When framing fails, culture vanishes

Each of these slogans collapses a rich and diverse body of evidence into a single moral label. The Heraklean cycle, as Emma Stafford and contributors to The Oxford Handbook of Heracles have shown, presents a composite figure who embodies civic duty, cosmic order, and human suffering in equal measure.

Medusa, as Françoise Frontisi-Ducroux’s Le monde du Gorgon and Kenneth Lapatin’s recent survey in the Oxford Handbook of Classical Mythology make clear, was primarily an apotropaic power whose gaze protected temples, homes, and entire cities; the later idea of her as a rape victim belongs to Ovid’s Roman retelling and to modern reinterpretations, not to Greek religion.

Nor were “all Greek women oppressed.” Sarah Pomeroy’s Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves first demonstrated the range of female experience across class and region, while Lin Foxhall’s Studying Gender in Classical Antiquity shows that women exercised ritual, economic, and domestic agency within complex civic systems, and neither Athens nor Sparta can abe upheld as models across city-states and rural Greece. Hera, as Jennifer Larson and Walter Burkert have detailed, was not a jealous caricature but a guardian of sovereignty and lawful marriage, her “anger” functioning as a mythic symbol of cosmic balance.

Persephone, in the work of Kevin Clinton and Helene Foley, is revealed as an initiatory power and co-ruler of the underworld, not a passive victim. Even the famous Apollo–Dionysos polarity, first popularised by Nietzsche, has long been dismantled: modern studies by Richard Seaford and Lisa Maurizio describe the two gods as complementary forces of order and renewal within a single religious continuum.

Together, this scholarship shows that what the internet turns into slogans are, in fact, intricate systems of meaning. To flatten them into moral fables about patriarchy, repression, or liberation, thereby colouring our understanding of a historical culture and, by extension, of the communities that continue to live within its linguistic and ritual continuum today, is not progress but regression: a return to the same habit of imposing our own categories on the past. It is no different to the pre-Champollion attempts to reinvent Egyptian hieroglyphics, with the attendant misconceptions that still plague Egyptology. And my ever shorter fuse when I encounter these slogans is directly correlated with their ubiquity.

Such interpretations have value only when framed as contemporary critical appropriations, not as historical truth-claims about Greek religion or society. Without that framing, each becomes a caricature that says more about modern anxieties than ancient worldviews.

These distortions have wider consequences. They not only mislead the public but also corrode living relationships with the past. In Greece, where ancient myth still shapes language, ritual, and everyday culture, turning those stories into ideological shorthand severs them from the contexts that give them meaning and breeds distrust toward scholarship itself.

Internationally, this same habit reinforces the view of the ancient Mediterranean as a single, oppressive system to be condemned rather than understood. The result is a kind of epistemic vandalism: complexity is stripped away until history is reduced to propaganda.

Positionality in brief

In this context, a further remark of mine was misinterpreted. I am intimately familiar with the culture in which I was partly raised. My immediate family’s origins span five countries on three continents, across four ethnicities and three religions, shaped by several diasporic migrations and two generations of refugees in both maternal and paternal lines. I speak five languages and am interculturally fluent across three of the cultures involved. I have studied Greek history and culture closely for years and experienced it both from outside, as an expatriate, and inside, having returned to its lived frame. Yet I have been told all my life that I am “too Greek” by some and “not Greek enough” by others. I made it the object of my study to understand why.

Anthropologists often study their own culture from within (a subdivision called Insider Anthropology that closely overlaps with sociocultural anthropology). As a cultural historian utilising an interdisciplinary toolbox drawing strongly on anthropology, I am obliged to be transparent about my positions on Greek culture, and have been so in every article I write.

So, when I call it “my own culture,” whether referring to historical or modern iterations, I am signalling an emic relationship alongside the etic one, grounded in situated cultural understanding through long immersion and through linguistic and historical literacy, not lineage or inheritance: both of which, in my case, are thin at best anyway.

Emic/etic are fundamental anthropological terms signalling objective outsider (etic) vs. insider (emic) experience of the phenomenon being studied (culture, ritual, social phenomenon, etc). It is a natural statement of positionality that in normal scholarly discourse signals transparency and self-reflexivity and that I expected to be read as such, particularly since my gender had just been invoked inappropriately.25 My objection to that was then distorted out of all proportion.

This episode has also been a costly reminder of how easily misplaced certainty wastes collective effort. I have had to divert precious time from other pressing matters to restate evidence that is already well established in the scholarship, simply because misreadings circulated on the basis of assumptions rather than due diligence .

It is frustrating to be forced to perform remedial work that should be standard within our field. I was recently informed about the dual meanings of terms in analytic philosophy, a domain I do not know well, and was fascinated to realise how those connotations can cause communication breakdowns simply due to disciplinary blind spots - in this case on both sides. And I was genuinely excited to learn about it. Once clarified, the discussion was productive despite a core theoretical disagreement. That is how scholarly dialogue should proceed: by examining one’s assumptions before drawing conclusions. This incident illustrates why such standards exist.

Academic freedom entails corresponding duties of method and context. Scholars working in public view— in the classroom, on the conference stage, in print, or online—carry a professional obligation to distinguish clearly between analysis and projection, evidence and analogy. The integrity of our disciplines depends on that clarity. Otherwise, let us not be surprised at the decline of the Humanities and the identity crisis facing Classics in particular.

Scholarly critique is often sharp, and it should be; argument is how knowledge advances. But it should never be taken as a personal attack, nor used as one, whether in formal or informal settings. Scholars are professionally bound to know the difference and to uphold it, and scholars who defend evidential accuracy or methodological integrity should never be accused of ideology for doing so.

To equate rigour and transparency with partisanship is to abandon the very principle of open inquiry on which the humanities rest. If we fail to uphold that distinction, we help to erode public trust and to feed the misinformation that thrives on simplification. The remedy is not self-censorship but transparency: say what lens you are using, what evidence it rests on, and where its limits lie. That is how genuine debate remains possible, and how understanding of the world - ancient and modern - continues to grow.

Where I stand

For the sake of clarity, it is worth restating that my own work operates from an interdisciplinary lens, drawing on textual study, archaeology and material culture, social anthropology, ethnography, and, where applicable, the natural sciences. I largely follow Margaret Alexiou, whose scholarship demonstrates the power of reading traditions both diachronically—across long continuities—and synchronically—within their particular historical settings. The aim is always to widen perspective, not to narrow it.

I am openly critical of approaches that reduce the record to a single disciplinary method or treat modern reinterpretations as historical fact, because both obscure more than they reveal. This is not a matter of identity but of poor results: understanding the past demands breadth of evidence and precision of frame. That principle holds for any culture, anywhere, and it is what keeps scholarship honest.

My concern has always been that monodisciplinary readings, whether narrowly philological or purely theoretical, risk flattening what they study. I am equally wary of modern reinterpretations that are not explicitly framed as such, because they turn historical material into mirrors for our own preoccupations. My position is therefore methodological: understanding the ancient world demands the widest possible evidence, set within the cultural and linguistic systems that produced it. There is no way this can be labelled ideological: if anything it is common sense.

Watch: Herakles in Hesiod

By way of demonstration of how nuance can be ensured even when there are no footnotes to hand (though there were further reading lists provided), here is the episode from my course on Hesiod’s Theogony in which I look closely at Herakles. For those wishing to jump straight to that section, it starts around the 1:25 timestamp, otherwise, you may enjoy the whole lecture. This piece and its footnotes now stands as the definitive evidence base for that section.

This course was created and delivered for Treadwell’s Events in Winter 2021. I have uploaded several more free episodes right here on Thyrathen, with additional segments for paid subscribers. Access the course here.

The scholarship has now been stated with precision. I am always happy to debate at a level of ideas, both formally and informally, but only in good faith. I will not tolerate any further misrepresentation of my person and positions on these matters, especially given the extent to which I have performed due diligence in every post to ensure my positions are clear.

In archaeology, terms like Neolithic and prehistoric have precise chronological meanings that differ sharply from how classicists use period labels. Prehistoric simply designates the span before written records, and in the Aegean that means roughly 7000–1100 BCE: the Neolithic through the Bronze Age. Archaeologists speak of “prehistoric Greece” or “Aegean prehistory” without implying ethnic continuity or mythic dating, only the material horizon from which later cultures inherit imagery and practice. When an archaeologist calls a motif Neolithic, it means it first appears in that stratum of the record, not that a later Greek figure existed then. The distinction between motif-age and myth-age is basic archaeological method and not in the least controversial, though it may be unfamiliar to those trained solely in textual studies.

Sources demonstrating this include: Colin Renfrew, The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in the Third Millennium B.C. (1972); Marinatos, Minoan Religion (1993); Shapland, Anna. The Emergence of Aegean Prehistory. Cambridge University Press, 2025.

A.N. Athanassakis (ed., trans.), Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022.

Bremmer, Jan. Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible, and the Ancient Near East. Brill, 2008.

Larson, Jennifer. Understanding Greek Religion. Routledge, 2007.

Seaford, Richard. The Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Shapland, Anna. The Emergence of Aegean Prehistory. Cambridge University Press, 2025.

Stafford, Emma. Herakles. Routledge, 2012.

Thomas, Nicolas. “Networked Iconographies: Motif Transmission in the Bronze-Age Aegean and Beyond.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 124, no. 4, 2020, pp. 491–522.

West, Martin L. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Otto, Bernd-Christian. (2023) 2023. “Introduction: Western Learned Magic As an Entangled Tradition”. Entangled Religions 14 (3).

Burkert, Walter. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Dougherty, Carol, and Leslie Kurke, editors. Cultural Poetics in Archaic Greece: Cult, Performance, Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Dowden, Ken. Death and the Maiden: Girls’ Initiation Rites in Greek Mythology. London: Routledge, 1989.

Graf, Fritz. Greek Mythology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

Larson, Jennifer. Understanding Greek Religion: A Cognitive Approach. London: Routledge, 2016.

Mariolakos, H. D. «Η Γεωπεριβαλλοντική Διάσταση της Ελληνικής Μυθολογίας.» Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας 34.6 (Πρακτικά 9ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Αθήνα, Σεπτέμβριος 2001): 2065–2086. DOI: 10.12681/bgsg.17334.

Mitropetrou, Elena P. Οι απαρχές της ελληνικής γεωμυθολογίας μέσα από τις κοσμογονίες, τις θεογονίες και τον κύκλο του Ηρακλή. Διδακτορική διατριβή, Πανεπιστήμιο Πατρών, 2012.Nanoglou, Stratos. “Representation of Humans and Animals in Greece and the Balkans during the Earlier Neolithic.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 18.1 (2008): 1–20.

Orrelle, Ella, and Steven Rosen, editors. The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013.

Piccardi, Luigi, and W. Bruce Masse, editors. Myth and Geology. Geological Society of London, Special Publication 273. London: Geological Society, 2007.

The Oxford Handbook of Heracles. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Wengrow, David. The Origins of Monsters: Image and Cognition in the First Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Mitropetrou, Elena P. Οι απαρχές της ελληνικής γεωμυθολογίας μέσα από τις κοσμογονίες, τις θεογονίες και τον κύκλο του Ηρακλή. Διδακτορική διατριβή, Πανεπιστήμιο Πατρών, Τμήμα Γεωλογίας, 2012. DOI: 10.12681/eadd/39437.

On Mariolakos see below.

Piccardi, L. “Active faulting at Delphi, Greece: seismotectonic remarks and a hypothesis for the geologic environment of a myth.” Geology 28.7 (2000): 651–654. DOI: 10.1130/0091-7613(2000)028<0651:AFADGS>2.3.CO;2.

Piccardi, L.; Monti, C.; Vaselli, O.; Tassi, F.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Papanastassiou, D. “Scent of a myth: tectonics, geochemistry and geomythology at Delphi (Greece).” Journal of the Geological Society 165.1 (2008): 5–18. DOI: 10.1144/0016-76492007-055.

Stewart, I. S.; Piccardi, L. “Seismic faults and sacred sanctuaries in Aegean antiquity.” Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 128.5–6 (2017): 711–721. DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2017.07.009.

de Boer, J. Z.; Hale, J. R.; Chanton, J. P. “New evidence for the geological origins of the ancient Delphic oracle (Greece).” Geology 29.8 (2001): 707–710. DOI: 10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0707:NEFTGO>2.0.CO;2

Kortekaas, S.; Papadopoulos, G. A.; Ganas, A.; Cundy, A. B.; Diakantoni, A. “Geological identification of historical tsunamis in the Gulf of Corinth, Central Greece.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 11 (2011): 2029–2041. DOI: 10.5194/nhess-11-2029-2011.

Karkani, A.; Evelpidou, N.; Tzouxanioti, M.; Petropoulos, A.; Gogou, M.; Mloukie, E. “Tsunamis in the Greek Region: An Overview of Geological and Geomorphological Evidence.” Geosciences 12.1 (2022): 4. DOI:10.3390/geosciences12010004.

Papadopoulos, G. A.; Gràcia, E.; Urgeles, R.; et al. “Historical and pre-historical tsunamis in the Mediterranean and its connected seas: a review on documentation, geological signatures, generation mechanisms and coastal impacts.” Marine Geology 353–354 (2014): 81–109. DOI: 10.1016/j.margeo.2014.04.014.

Kortekaas, S.; Papadopoulos, G. A.; Ganas, A.; Cundy, A. B.; Diakantoni, A. “Geological identification of historical tsunamis in the Gulf of Corinth, Central Greece.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 11 (2011): 2029–2041. DOI: 10.5194/nhess-11-2029-2011.

Papadopoulos, G. A.; Gràcia, E.; Urgeles, R.; et al. “Historical and pre-historical tsunamis in the Mediterranean and its connected seas: a review…” Marine Geology 353–354 (2014): 81–109. DOI: 10.1016/j.margeo.2014.04.014.

See above

Mariolakos, I.; Theocharis, D. “Geomythological approach of Asopos River (Aegina, Greece).” Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece 43.2 (2010): 821–828. DOI: 10.12681/bgsg.11248.

Mariolakos, H. D. “The geoenvironmental dimension of Greek Mythology.” Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece34.6 (2002): 2065–2086. DOI: 10.12681/bgsg.17334.

Mariolakos as above, also Piccardi, L.; Masse, W. B., eds. Myth and Geology. Geological Society of London, Special Publication 273 (2007).

Liritzis, I.; Westra, A.; Miao, C. “Disaster Geoarchaeology and Natural Cataclysms in World Cultural Evolution: An Overview.” Journal of Coastal Research 35.6 (2019): 1307–1330. DOI: 10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-19-00035.1.

Soter, S.; Katsonopoulou, D. “Submergence and Uplift of Settlements in the Area of Helike, Greece, from the Early Bronze Age to Late Antiquity.” Geoarchaeology 26.4 (2011): 584–610.

(Context update) Seismological re-assessment: “The 373 B.C. Helike (Gulf of Corinth, Greece) Earthquake” Seismological Research Letters 93.1 (2022): 444–459.

Walter Burkert, Homo Necans, Introduction, XIX.

(Orrelle and Rosen 2013; Wengrow 2013; Nanoglou 2008)

(Piccardi and Masse 2007; Mariolakos 2001).

Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States (1896–1909); Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1903).

Nilsson, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion (1927); discussion in Buxton, The Complete World of Greek Mythology (2004).

Otto Rank, The Myth of the Birth of the Hero (1909); C.G. Jung and K. Kerenyi, Essays on a Science of Mythology (1941).

Stafford, Emma. Herakles. Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World, Routledge, 2012.

Fuqua 1980; Rosenmeyer 1993; the Oxford Handbook of Heracles

Rosen, Ralph, and Ineke Sluiter. Andreia. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 31 Jul. 2017.

Vickers Michael. Heracles Lacedaemonius : the political dimensions of Sophocles Trachiniae and Euripides Heracles. In: Dialogues d’histoire ancienne, vol. 21, n°2, 1995. pp. 41-69.

Alcoff, Linda. Cultural Feminism Versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society Vol.13, no.3 (1988).

Takacs, David. How Does Your Positionality Bias Your Epistemology?, Thought & Action Thought & Action 27 (2003). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/1264

Honestly you provide so much value here you deserve to take a week or two off once in a while.

So well said. All of it.